- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

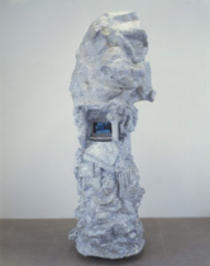

The cadences of an auctioneer greet the visitor to an exhibition of Rachel Harrison’s work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, but this is not Sotheby’s. It’s a low-rent auction. The bids come in one- and two-dollar increments, and there are no British accents. Intrigued by the galloping voice, you discover its source: a towering, amorphous, silvery blue, concrete mass entitled Hail to Reason. Although vaguely resembling Auguste Rodin’s Monument to Balzac in its tall, oblong shape, Hail to Reason does not represent anything in particular. Instead, it offers a lumpy surface punctuated by alcoves ideal for resting a wine glass or hors d’oeuvres during an opening. As if foreseeing this possibility, Harrison attached a package of doilies to the piece’s exterior.

Circling the sculpture, you find a portable DVD player lodged inside the work’s craggy exoskeleton. On the screen, an amateurish, handheld video of an auction plays, showing men, women, and boys stepping forward to offer an eclectic range of goods. Most of the items, like Harrison’s forlorn doilies, do not inspire, yet each one sells. (I later learned that the footage is from a weekly event held in upstate New York.) The video sucks you in. You never know what might be next on the block, and, soon enough, you have been gawking at this piece longer than you ever take to inspect a typical sculpture. One wonders: Is this a video installation rather than a sculpture? Or perhaps a sly reinvention of Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making? Peering more intently at the cement-slathered forms (auctioned objects?) encased within the work, one is indeed “hailed to reason.” While gesturing toward the experiential ambiguity of Morris’s piece, Harrison’s work also invokes Rosalind Krauss’s writing on the essentially “nomadic” character of modernist sculpture. In her essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” speaking of Rodin’s Balzac, Krauss contends that “it is the modernist period of sculptural production that operates in relation to this loss of site, producing the monument as abstraction, the monument as pure marker or base, functionally placeless and largely self-referential” (The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths [Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985], 280). As if burlesquing the author’s argument, Harrison attaches tiny wheels to Hail to Reason, creating a literally siteless monument, a rolling, self-referential abstraction. Unfortunately, the DVD player confounds this mobility, condemning the wayfaring sculpture to stray only as far as its extension cord allows.

Unlike much contemporary art, Harrison’s pieces resemble “traditional sculptures,” though they tend to function not so much as self-contained objects as playful commentaries on the history of art and art’s engagement with technology. Another work, Blazing Saddles, makes this orientation explicit. Named after Mel Brooks’s 1974 movie comedy, Blazing Saddles is a six-foot-tall wooden pillar, boxy and uniformly brownish. If Louise Nevelson were to construct an anthropomorphic column, it might look something like this. However, Harrison’s “miniature Nevelson” is incongruously crowned with a Warholesque cardboard box labeled “Campbell’s Barbecue Beans.” The sculpture’s lower register exudes the expressiveness of manual construction, while the Campbell’s carton presents a bland cipher for the hands-off Pop artist, setting up an enigmatic juxtaposition of the high modernist and the ultrapostmodern. As with Hail to Reason, interpretive options multiply as one moves around the work. In this case, on the far side of the sculpture hangs a framed and matted picture of Lucille Ball displayed at eye level. However, this is not just Lucy but a production still of the pre–I Love Lucy Lucy, from the 1950s film The Fuller Brush Girl (or so says the wall text). In the still, two little boys in cowboy gear stand on either side of her, training miniature six-shooters on the comically distressed actress. More than anything, this image, like the sculpture as a whole, revolves around the clash of contrasting media and messages: this is not simply a black-and-white photograph of a television star in a B movie, but also a representation of a young female artist under duress. As such, the production still narrates the status of Harrison’s larger sculptural artifact: Blazing Saddles unfolds between the competing demands of the modern and postmodern. This is a sculpture created under the art-historical gun.

Harrison’s works tend to have “fronts” and “backs” that prod ruminations on the flow of perception and the digestion of information. Unlike most installation art, her sculpture does not typically expand outward, enveloping the viewer’s body. Instead, it turns aggressively inward, intertwining perplexing concatenations of cultural material that reveal themselves only gradually. The exhibition’s other works follow this paradigm: Marilyn with Wall features the source image for Andy Warhol’s iconic rendering of Marilyn Monroe, affixed to a chopped-up shard of the museum’s drywall; a like-minded object, Cindy, offers a thin slab of white Sheetrock that leans against a lime-green stack of living-room furniture topped by a discount store blond wig. Imagine, if you can, a lazy Sol LeWitt–like modular pyramid slapped together from the domestic accoutrements for one of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills. These works exude an overpowering sense of construction and capriciousness, as if Harrison’s objects evolved from idiosyncratic Internet searches (“postmodern, modern, female artist, comedy, cowboys,” yielding Blazing Saddles).

Perhaps it is fitting, then, that Harrison’s career uncannily mirrors the expansion of the Internet; she first submitted work to group shows in the early 1990s, just as the World Wide Web appeared on the public’s radar screen. Similarly, she had her first solo show in 1996, the year in which the Internet exploded into the popular consciousness. Not overtly high tech, Harrison’s art joins the genealogy of handmade artworks that have laid bare the rhetoric of modern technology, from Édouard Manet’s painterly riffs on the photograph, to the filmic language of Pablo Picasso’s collages, to the televisual presence of Robert Rauschenberg’s combines. Harrison’s sculptures traverse a Googled universe. And as you leave, the auctioneer’s barked bids no longer suggest “Sotheby’s.” They scream “eBay.”