- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

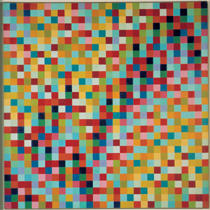

Beyond Geometry: Experiments in Form, 1940s–1970s makes modern art’s recent past reflect meaningfully on the present. The word “beyond” in the exhibition’s title promises a look at evidence not covered or hidden by the noun to which it is attached. Although the years from 1940 to 1970 press for breadth, they also situate the exhibition in a specific era with no claims for timeless transcendence. In modern art, form—as separate from content—has a suspenseful, contentious history. During the Cold War (and even before, in Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union), form and formalism were demonized and censored by the content-driven, socialist realist aesthetic of the Eastern bloc. Yet our post–Cold War, post-postmodern time has evolved past such naïve dyads, with form as, rather than opposed to, content. Janus-faced, Beyond Geometry focuses on specifically circumscribed definitions of form in various media, with an awareness of their potential for stirring new thoughts that expand beyond the period covered. Indeed, the formal strategies adopted in various countries at about the same time, as well as the underlying dialogue perceptible in the artists’ work, parallel today’s global flow of information and ideas. Indeed, the exhibition, as described in its catalogue foreword, presents its case as “an essay rather than a survey” (7).

Beyond Geometry is designed for both the newcomer and the connoisseur, and it is the savoir-faire of its curator, Lynn Zelevansky of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), that accomplishes this challenging task. The first noticeable feature is the exhibition’s geographical stretch: art from South America and Central Europe appear alongside familiar work from Western Europe and the United States. Beyond Geometry derives its meaning and appeal from the mapping of territories joined and disjoined by a common goal, that of taking formal experimentations beyond the boundaries of its early modernist stage.

The exhibition is divided into six sections: “The 1940s and 1950s,” “The Object and the Body,” “Light and Movement,” “Repetition and Seriality,” “The Object Redefined,” and “The Problem of Painting.” As installed at LACMA, these sections overlapped, which was occasionally disorienting. Yet, with assistance provided by short explanatory texts posted on the walls, the exhibition’s divisions functioned well as guideposts to the continuities and inflections that the main theme of the show underwent over time. The section “Light and Movement” included a “Sound Room,” with recordings of music playing through speakers, and “Repetition and Seriality” displayed concrete poetry, some on the wall, some in vitrines. The inclusion of a book of concrete poetry from 1964 by Václav Havel, the dissident playwright and writer who after 1989 became the first president of the Czech Republic, was a pleasant surprise. These additions caused provocative shifts in perception and attention and counteracted monotony, in addition to having informational, contextual value. The catalogue essays by Brandon LaBelle (on formal experiments in music) and Peter Frank (on concrete poetry and artists’ books) offer valuable insight into these subjects.

In Europe, a formal, nonobjective, impersonal art founded on mathematics was sketched out and even named “concrete”—in contrast to abstract art still rooted in referential matter—in the years before World War II. Yet the geographically expanded, more self-conscious, and dialogic history of this rational and geometric art may be properly traced to the years after the war, when artistic formalism gained international attention as a response to the war’s overwhelming chaos. In the visual arts, concrete art was an alternative to lyrical abstraction and figuration, the latter mode heavily prescribed in the Soviet-ruled Eastern bloc countries. The early practitioner and messenger of concrete art who influenced both European and South American artists was Max Bill, the Swiss artist, architect, teacher, and former Bauhaus student. Yet the South American version of concrete art on display at LACMA is noticeably different from Bill’s version. Whimsical, unruly, and off balance, the shaped panels, paintings, and sculptures produced by the various artists’ groups that sprung up in mid-twentieth-century Brazil (Grupo Ruptura, Grupo Frente, the Neoconcretists) and Argentina (Arte Madí) diverged from and argued with Bill’s dull and predictable compositions, and with his definitions of the concrete. Of different inspiration and persuasion, radical left-wing artists in South America rewrote the canon of geometric art while also breaking with the Stalinist taboo on formalism. Valerie Hillings’s catalogue essay “Concrete Territory: Geometric Art, Group Formation, and Self-Definition” and Aleca Le Blanc’s “Chronology” answer questions concerning the spread and the often-contentious dynamics of concrete art on the three continents.

While artists in the international scene expanded and diversified their formal experiments in the 1960s, Minimalism, a movement born and grown in the United States, made consequential propositions self-consciously distinct from the European or international paradigm. Undoubtedly, Minimalist structures—with their grand scale, industrial anonymity, and antipathy to composition—looked highly unfamiliar to critics and the public; their unrelenting antiaesthetic program was imposing. Yet, Beyond Geometry offers a more interactive and less alienated view of Minimalism, suggesting a lineage and continuities usually bypassed or even denied by the critical discourse and the artists’ statements; these continuities return to the very definition of concrete art. Once again, works by South American artists such as Aluísio Carvão, Cildo Meireles, and Hélio Oiticica insert excitement, color, and lively dialogue with both the worldwide art scene of their time and today’s museum-going public. Beyond Geometry affixes a context to, and a critical vista concerning, the recent exhibition A Minimal Future? Art as Object 1958–1968, held March 14–August 2, 2004, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, which overlapped the show under review.

Beyond Geometry concludes with a lively selection of Conceptual art. Although this movement preserved some of the previous methods and devices of geometric formalism, it emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s in diverse media on the three continents sampled in the show. Activated by a critical awareness of the politics of art and in protest of the absurd and destructive politics of the Vietnam War, Conceptual artists abandoned and/or critiqued object-driven art and the museum and gallery systems in favor of alternative means of exhibition and dissemination of art. With the “concrete” absent or drastically rephrased, new forms of attention and documentation replaced habits of perception, inviting the public to participate in novel ways. With its remarkable referential inclusiveness and dematerialization (as opposed to the exclusive, material-oriented programs preceding it), the Conceptual works in the exhibition raise the question: Is this the most extreme “beyond” of geometry, as suggested by the exhibition? And would the beyond of this beyond be rightly designated a “problem,” as the title of the sixth and last, and somewhat expeditiously assembled section, “The Problem of Painting,” suggests?

It is perhaps better to leave these questions unanswered, since Beyond Geometry asks many others, such as those raised by twenty-first-century digital art, the iconoclasm of geometric art in general, and the broader relationship between art and science. The exhibition (once again the curator’s merit) situates art as an irreplaceable partner of science, one that makes unique contributions to our cognitive and perceptual being in the world. The innocent charm and fun, not unlike that of silent-era films, conveyed by some of the technologically “clumsy” artworks seen at LACMA, such as François Morellet’s buzzing 4 Self Distorting Grids or the mysteriously dumb Pulsating Structure by Gianni Colombo, make this point fully understandable. In no arrogant competition with science, art is allowed to be funny and to thrive on the unknown. Art borrows from science—it would do well for science to learn from art. Miklos Peternák’s catalogue essay approaches the demanding subject of the art-science relationship with an open-minded and well-informed background.

All in all, rather than providing authoritative answers, the sequential design or “narrative” of Beyond Geometry, including its revisionism as interpreted by the curator’s choice of examples and her will to take risks, invite the public’s questions and provokes thoughts. If this is the purpose of essays, the exhibition accomplished its task. Con brio.

Sanda Agalides

Faculty, School of Critical Studies, California Institute of the Arts