- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

In 1967, the first pages of the publication La Raza were printed in the basement of the Church of the Epiphany, in Lincoln Heights, Los Angeles, under the encouragement of Father John Luce, an Episcopalian priest who supported the Chicano Civil Rights Movement (also known as El Movimiento). Over the next ten years and the course of four dozen issues, the newspaper chronicled El Movimiento, expanding into a magazine in the process. By 1977, conflict, political repression, and exhaustion had caused the movement to wane, and La Raza ceased publication. Throughout that time, an archive of nearly twenty-five thousand film negatives was amassed, and they are now housed at UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center. The exhibition La Raza, which was sponsored in conjunction with the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA” initiative and cocurated by Amy Scott and Luis C. Garza, marks the first large-scale presentation of this archive. And yet, with over two hundred photographs on display, the exhibition represented a small percentage of its holdings.

A section titled “The Principals and the Newspaper” laid the groundwork to introduce the publication’s key figures, including cofounders Ruth Robinson and Eliezer Risco, and its history. Although La Raza’s staff and offices were subject to harassment and raids by the Los Angeles Police Department, a core group of photographers emerged from within La Raza’s volunteer staff: Pedro Arias, Manuel Barrera, Patricia Borjon, Oscar Castillo, Luis C. Garza, Gilbert Lopez, Maria Marquez-Sanchez, Joe Razo, Raul Ruiz, Maria Varela, Devra Weber, and Daniel Zapata. Many of the photographers were self-taught, but a culture of collective mentorship emerged, an interplay of influence and intellectual exchange suggested in the portraits that Lopez and Barrera produced of each other. The display of La Raza’s published issues at the Autry Museum demonstrated its evolution from a newspaper to a full magazine, serving as a condensed visual record of the range of subject matter covered, and the increasingly significant role that photography played throughout its history.

As a sampling of La Raza’s archive, the exhibition could be interpreted through multiple lenses, one of which included the stylistic evolution of a cohort of photographers. Unattributed photographs were interspersed among works by the principal staff, making it possible to notice compositional motifs that served as aesthetic signatures for individual photographers. This pointed to one vector of the exhibition’s art historical significance: the photographs in this show remedied an absence of Chicano photography in historical studies, which have predominantly favored conceptual work and have yet to examine the work of Movimiento-era photographers. La Raza’s staff also traveled within domestic and international circuits, which brought them into conversation with an eclectic range of artists and thinkers.

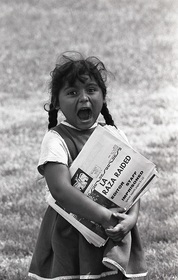

The exhibition was centered on the political activism at the heart of the movement, and was organized around five themes: “Portraits of a Community,” “Action, Agency, and Movement,” “Signs of the Times,” “The Body,” and “The Other and the State.” As a whole, the exhibition swiftly shifted between images that document historical moments and everyday life, suggesting that this slippage and movement is emblematic of eras marked by political unrest. An image by Raul Ruiz that synthesizes this negotiation shows Mickey and Silvia de la Peña marching in the 1970 National Chicano Moratorium. Dressed in formal wedding attire, they join the procession with exuberant faces, suggesting the movement’s capacity to contain joy within moments marked by urgency and political anguish. The photograph was included within “Portraits of a Community,” which documented the complex and multiple ways that Chicanos articulated their identities through music, theater, social ties, and self-fashioning. This visual record augments and complicates readings of the movement that propose an ideological or cultural monolith. A curatorial approach that does not try to resolve this multiplicity but rather offers it as a site for contemplation is precisely what made the exhibition an intellectually generative experience. By offering context but resisting the urge to produce a comprehensive or singular narrative, the exhibition effectively responded to the challenges of displaying a large volume of material that chronicled the Chicano Civil Rights Movement for the first time.

The volume of material included within the exhibition resulted in visually dense arrangements, with many sections hung salon style. The curators, however, strategically utilized scale to enliven the viewing environment and expand the scope of visual material on display. In addition to photographs, the accompanying publication also featured intricate illustrations by E. E. Garcia that used symbol and allegory to formulate structural political critiques exceeding the frame of a single photograph. The curators included a selection of these illustrations enlarged to life-size throughout the exhibition. The inclusion of this material represented a significant body of work yet to be considered by art historians of print and political graphic art. The curators further shifted viewers’ relationships to the photographs through the use of large, vertical light boxes installed in the center of the exhibition that displayed images emblematic of its five thematic focuses. Elsewhere, an interactive touch table enabled visitors to navigate the archive through multiple routes, whether through geography, chronology, or a detailed index. While dynamic network visualizations illustrated the interconnections between material on a large scale, viewers could also proceed image by image, including out-of-focus and unattributed shots.

It was in “The Other and the State” that the curators’ interventions in viewers’ interaction with the material had their greatest impact. A selection of photographs documenting police surveillance of protestors (and the publication’s countersurveillance) were installed near the top of the wall, evoking the unease that the experience of being monitored elicits and the challenge to authority that returning its gaze poses. The section also prominently featured an enlarged contact sheet of photographs by Joe Razo and Raul Ruiz, the publication’s coeditors, documenting the LA County Sheriff’s deputies surrounding the Silver Dollar Cafe during the Chicano Moratorium. The images show their movement moment to moment as a deputy approaches, aims, and shoots a tear gas canister into the bar. Unbeknownst to Razo and Ruiz, the journalist Ruben Salazar, an advocate for the Chicano Civil Rights Movement and an outspoken critic of the LAPD, was inside the bar and killed instantly. Razo and Ruiz’s images have become emblematic of the Chicano Moratorium and have served as visual references for artists working in other media. This series was surrounded by photographs documenting the injuries and casualties inflicted by the LAPD on Chicanos and Mexican Americans, demonstrating the normalization of a violent orientation toward this community.

Although events that resonate with issues central to the Chicano Civil Rights Movement—such as police harassment, discriminatory educational conditions for Mexican Americans, the disproportionate number of Chicanos drafted to the Vietnam War, and labor conditions for farmworkers—held a prominent place within the exhibition, it also spoke to the movement’s tremendous scope and to recurring moments of overlap with parallel activist movements. A photograph by Luis C. Garza distills the points of resonance between El Movimiento, the Black Panther Party, and the Young Lords: it shows a woman affiliated with the Young Lords in the South Bronx holding an issue of Palante, the party’s own newspaper, with an image of Huey P. Newton on its cover. Throughout each of the exhibition’s thematic sections, the publication’s coverage of protests indicated the breadth of issues that motivated Chicano political activism, including representation within film, women’s rights, immigrant rights, reproductive justice, prison conditions, workplace discrimination, the Watergate scandal, Puerto Rican liberation, the arrest of Angela Davis, the 1968 Plaza de Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City, the 1973 US-backed coup in Chile, and the American Indian occupation of Wounded Knee the same year.

The exhibition La Raza announced the arrival of a substantive body of work by more than a dozen photographers due for additional scholarly consideration. Whereas many exhibitions seek to frame artwork through a single lens, the photographs on view in La Raza offered an expanded visual lexicon from the Chicano Civil Rights Movement that speaks to the intersections of activism, gender, performance, and identity with visual culture in a transnational context.

Mary Thomas

Postdoctoral Associate: Mexican American Art since 1848, Department of Chicano and Latino Studies, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities