- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Georgia is a country in the Caucasus with a strong tradition of Eastern Christian art. Secular visual art developed here in the early twentieth century. Although it had been part of the Russian Empire since the early nineteenth century, Georgia enjoyed a brief period of independence as a democratic republic from 1918 to 1921. The capital, Tbilisi—or Tiflis, as it was then widely known—became an important destination for intellectuals fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War. The city also quickly became a center for the international avant-garde. This overlooked chapter from the history of European modernism recently received attention in the form of a major exhibition at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

Curated by Iveta Manasherova and Elena Kamenskaia, The Georgian Avant-garde: 1900–1930s: Pirosmani, Gudiashvili, Kakabadze, and Other Artists is a broad survey of works by Georgian and international artists active in Tbilisi during the first three decades of the twentieth century. The curators selected two hundred paintings, graphic works, and sketches of stage designs from museums and private collections. These objects reveal an avant-garde with a distinct trajectory that differs from the pathways carved by the St. Petersburg and Moscow avant-gardes.

The first floor of the exhibition is entirely dedicated to the work of the versatile, cosmopolitan artist Davit Kakabadze. Educated in private art studios in his native Kutaisi, Kakabadze developed an interest in medieval Georgian architecture, as well as in theater design and photography. He first encountered avant-garde art in the early 1910s while studying physics and mathematics at the Imperial University of St. Petersburg. When he returned to Georgia at the end of the decade, Kakabadze became active in Tbilisi’s artistic milieu. The Pushkin Museum’s display focuses on the artist’s Parisian period (1920–27), during which he explored the vocabulary of western European modernism. Kakabadze’s first Paris paintings owe as much to his interest in the work of Picasso and Braque as to Kazimir Malevich’s Futurist “a-logical” paintings, which combined seemingly incompatible objects with random words and letters. The curators chose to show several of the Cubist cityscapes and still-life paintings that Kakabadze produced in the early 1920s. Some of them imitate collage through their meticulous renderings of different textures and patterns, while others, such as Cubistic Composition, create dynamic, yet somewhat somber images of the modern city by combining sharp angles and diagonals rendered in a dark palette.

At the end of the room and in the adjacent corridor, one can observe Kakabadze’s progression toward the production of colorful, abstract biomorphic collages formed from combinations of paint, metal, wood, mirrors, and lenses. These works were inspired by the artist’s interest in the genesis of organic forms, optics, and the physiology of vision. By displaying these works in the first part of the exhibition, the curators invite visitors to understand Kakabadze’s original contribution to European modernism as a series of experimental, abstract collages that raise questions about the corporeality of vision.

Continuing the show’s internationalist focus, the objects displayed on the second floor reflect the cosmopolitan atmosphere of early twentieth century Tbilisi, or “Little Paris,” as it was called at the time. These works reveal that artists of different nationalities, credos, and creative methods made up the city’s avant-garde. To the right of the entrance, a corridor display documents fruitful collaborations between the young artists who traveled between Georgia and the heart of the Russian Empire in the 1910s, and later, between those who found shelter in Tbilisi after 1917. The left side of the display includes Georgian and Russian copies of Futurist periodicals, photographs of artists’ gatherings and exhibitions, and Futurist “books,” small-edition lithographed brochures that integrate experimental “trans-rational” (zaum) poetry with drawings and collages.

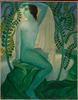

The three rooms that run parallel to the corridor are devoted to figurative works. Lado Gudiashvili’s paintings and drawings dominate this display. Like Kakabadze, Gudiashvili also studied in Paris. His refined, elongated figures set against colorful backgrounds reveal his interest in Persian miniatures, while also referencing the visual languages of French symbolism, Cubism, and early Art Deco. Gudiashvili’s graceful silhouettes and sophisticated compositions emerge even more strikingly in the pencil drawings of dancing beauties, horsemen, carousels, and the other Georgian scenes that he produced in the early 1920s. Drawing upon the subject matter of Impressionism and post-Impressionism, as well as the work of the Georgian primitivist painter Niko Pirosmanishvili, Gudiashvili developed an intense color palette, which he used to depict expressive Georgian faces. Gudiashvili set these images against landscape scenes, which he rendered in a decorative manner influenced by Georgian medieval frescoes. This synthesis of Western and Eastern artistic legacies makes Gudiashvili an outstanding representative of the stylistic diversity that is characteristic of the Georgian avant-garde.

A remote room on the second floor finally brings the visitor to the Soviet Georgia of the 1920s and 1930s, a period when, as Mzia Chikhradze explains in her article “A City of Poets,” avant-garde experiments were possible only in theater and film.1 This room features the work of experimental modernists Irakli Gamrekeli and Petre Otskheli, two artists with quite different approaches to stage design. The curators’ choice of works highlights Gamrekeli’s Cubist and Constructivist sets and Otskheli’s lyrical and Symbolist sketches for props and costume designs. Both artists, who worked with the innovative theater director Kote Mardzhanishvili, contributed to the multilayered picture of the Georgian avant-garde; they gave the old Georgian tradition that had already been affected by European theater’s influences in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries a distinctly modernist form.

The exhibition’s third floor is primarily dedicated to the self-taught primitivist painter Niko Pirosmanishvili, better known as Pirosmani, whom the Zdanevich brothers and their Russian colleague Mikhail Le Dantiu discovered by chance in a Tbilisi tavern in the summer of 1912. Though unaware of contemporary Western artistic movements, Pirosmani favored pictorial flatness, simple compositions, sharp outlines, and a limited number of plain colors, including black, white, brown, green, and red, which resonated with modernist aesthetics. In their articles for the exhibition catalogue, Luigi Margarotto and Marina Medzmariashvili explain the rapid popularization of Pirosmani’s work in Georgia and Russia as an effect of other artists’ perception of Pirosmani as a free thinker, “unspoiled” by formal education (30; 67–8). The curators chose to display twenty-two of Pirosmani’s paintings, mostly large compositions rendered in a modest palette, which use reverse perspective to represent biblical themes. Some also depict traditional Georgian characters and scenes such as feasts, wine cultivation, and herding. Although the artist himself was not a member of the Tbilisi avant-garde, Pirosmani’s use of a cosmopolitan visual language to render scenes from everyday Georgian life inspired and influenced Little Paris’s younger generation of artists.

The exhibition catalogue presents not only a great number of color images, but also a collection of ten essays by Georgian, Russian, British, and French art historians. The authors provide the reader with rich historical context and in-depth explorations of the Georgian avant-garde as a component of the increasingly global modernisms of the early twentieth century. The majority of these texts focus on Tbilisi as a vibrant city bursting with avant-garde movements, artistic cafes, exhibitions, poetry, and experimental theater. While acknowledging the peripheral and belated character of the Georgian avant-garde, the authors underscore the important role that Tbilisi played in the geographical development of the global avant-garde because of its critical position between Europe and Asia. In his essay “The Avant-Garde in Tiflis,” John E. Bowlt argues that the history of the European avant-garde is the history of the globalization of radical aesthetic ideas (91). As Bowlt and other authors demonstrate, the dialectics of tradition and modernity, of the national and the cosmopolitan that characterize the avant-garde in general, acquired special poignancy in Tbilisi due to its location, Georgia’s belated modernization, and the city’s role as a magnet for intellectuals at the moment of the Russian Empire’s disintegration (16, 59, 94).

The exhibition, by grouping diverse artworks together under the heading of “Georgian avant-garde,” provokes questions about the relationship between tradition and modernity and confirms the possibility of the existence of multiple avant-gardes. However, the exhibition only briefly mentions the terrible story that concludes this bright chapter of twentieth-century art history: that of Stalinist repressions in Soviet Georgia in the 1930s, which ultimately resulted in the murder of some of the artists, including Otskheli, represented in the exhibition and the exile of others. Ketevan S. Kintsurashvili outlines this tragic afterlife of the Georgian avant-garde in his catalogue essay (135–6). The works produced during the 1930s in Soviet Georgia still await careful exploration by art historians and curators in Georgia, Russia, and beyond.

1. Mzia Chikhradze, “A City of Poets,” Modernism/modernity 21:1 (2014): 302.

Yulia Karpova

Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies, University of Copenhagen