- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

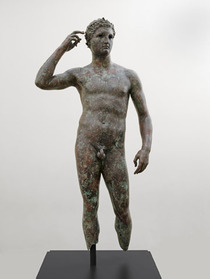

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World, curated by Jens M. Daehner and Kenneth Lapatin, opens with an empty limestone base from Corinth featuring cuttings for the feet of a bronze figure and inscribed “Lysippos made [this].” In his Natural History (34.37), Pliny credits Lysippos with creating 1,500 bronze statues, none of which have survived. The base serves as a stark reminder of how few large-scale bronze sculptures remain today while also presaging themes explored in this remarkable exhibition. The Hellenistic period stretched from the late fourth-century BCE reign of Alexander the Great until the rise of Augustus following the defeat of the last Hellenistic kingdom. Alexander’s empire spread from Macedonia and Greece to Egypt, across Asia Minor and Persia to the borders of India; after his death, Alexander’s generals and their successors ruled its fragmented regions and city-states. Their attempts to emulate Alexander resulted in the growth of ruler cults. Alexander favored Lysippos above all other sculptors, claiming he alone captured not only his likeness but also his passionate character. The exhibition features eleven portraits of Hellenistic rulers, all male and all images of power. These highly individualized visages portray specific, flesh-and-blood personalities as opposed to the idealized figures of gods, heroes, and generic athletes that characterize the earlier classical period. In addition to anatomical accuracy, artists emphasized psychological realism and lived human experience: pathos. Images of power and pathos distinguish the bronze sculptures cast throughout diverse regions in this period.

Since the era of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, many scholars have looked down on Hellenistic art, dismissing it as derivative and decadent, certainly no match for the seemingly unsurpassable achievements of the preceding classical period. Art theorists considered the agitation and frank outpouring of emotion displayed by many Hellenistic works to pale before the studied gravitas of classical art. In recent decades, however, the estimation of Hellenistic art has undergone a profound reevaluation. Scholars now recognize a heightened level of drama, the product of a new and unprecedented relationship between the work of art to its surroundings. Far from an inferior version of classical art, Hellenistic art is appreciated as one of revolutionary innovation and technical, formal, and psychological achievement. The figures of earlier Greek art looked off into the distance and occupied a world apart. The sculptures seen here, by contrast, present poses and gestures that appear calculated to focus the work beyond itself, infusing the immediate environment with a kind of electrical charge and making the viewer a part of the implied narrative. The famous Terme Boxer turns and stares upward and outward, as if beseeching the spectator for sympathy or even deliverance from the brutality of his plight.

An understanding of the achievements of Hellenistic artists has been affected by the paucity of surviving material. Many of the period’s statues survive as marble copies made early in the years of the Roman empire, which provide only an echo of the period’s artistic accomplishments. The Louvre’s Nike of Samothrace is one of the few monumental originals to survive and help impress the period on our consciousness. Notably made of Parian marble, even this powerful monument cannot convey the qualities of the era’s preferred medium: bronze. Light reflects from and animates bronze in ways not possible with marble, allowing for an interplay with light and shadow, a constantly changing interaction that enlivens the figures. The variety of these illusionistic effects ranges from sharp highlights glinting off tendrils of hair to a soft, modulated sheen sliding across a body. The surface can be worked after casting with tooling and patination. Hellenistic sculptors exploited both techniques to create startling effects, such as the colored bruise under the Terme Boxer’s right eye.

Since it is cast hollow, bronze is lighter and has greater tensile strength than marble, allowing artists to experiment with a greater range of physical expression. The top-heavy human form can be shown in more naturalistic, dynamic poses without breaking off at the ankles, always a problem with dense marble. Figures stand tall and free, without the exposed struts or supports—those bulky tree trunks or vases—found in marble copies. Lysippos was prolific because he forged parts from molds and existing pieces that could be mixed and matched with newer ones. The original models for sculptures were carved in wax, which was ideal for detailed articulation and afforded artists greater malleability when sculpting delicate facial features. Due to corrosion over time, today most bronzes feature a variety of colorful patinas; however, they once bore a tone similar to that of olive or dark, complected skin. Artists sometimes augmented sculptures with color and furnished them with silver fingernails, copper lips and nipples, ivory teeth, fine copper eyelashes, and glass eyeballs to create a lifelike illusion. The result was preternatural, near-pictorial levels of illusionism. It is little wonder that portraiture flourished in this period.

In addition to rulers, the exhibition features artisans, athletes, anonymous civic leaders, wealthy patrons, fellow citizens, and the deceased, all arranged in thematic groupings. No matter the subject, the statues from this period are mimetic; they are meant to be so realistic that they conjure the aura of the person represented. They clearly demonstrate the period’s desire to show age, social status, and, most importantly, what a person looks like. Images of gods appear less withdrawn from this world because they are less idealized and more realistic, at times even empathetic. Whatever the subject, the works exhibited here document artists’ determination to capture the world as they saw and experienced it with maximum truth.

The exhibition affords the viewer an extraordinary opportunity to consider several of the problematic issues presented by Hellenistic art, including workshop practices, replication and adaptation of types, conservation and restoration, and more. Apoxyomenos, excavated from Ephesos and lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, is a standing nude athlete who uses a strigil to scrape oil, sweat, and dirt from his body following competition. The statue is displayed with a larger-than-life version discovered in 1997 off the coast of Croatia in the Adriatic Sea, a later head of the same type from the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, and a basanite torso, also of the same type. Studying the same subject through three bronzes and one stone work allows us to truly understand the unique qualities of the material and consider the possibility that this popular “Ephesos type” (also known in nine other possible versions), rather than the unique Vatican version, actually reproduces Lysippos’s famous original, an interpretation first proposed by Carol Mattusch. Hellenistic artists looked back and drew inspiration from the preceding history of Greek art. The Piombino Apollo, the Spinario, the Idolino, and other works demonstrate how Hellenistic artists employed and adapted features from archaic and classical art to purposefully recall those earlier periods. Such stylistic eclecticism has often been cited to dismiss the art of the Hellenistic period as unoriginal, but the quality of such pieces demonstrates the technical virtuosity of the artists and speaks to the sophistication of their patrons. The catalogue essays by ten scholars delve deeply into these and other issues, including determining important centers of production and the contexts of modern discovery. The curators’ superb introduction, which provides a highly readable overview of the exhibition’s primary themes concerning the introduction of new subject matter and stylistic innovation in the Hellenistic period, as well as the technical and aesthetic analysis of the bronze medium, will become a standard reference for years to come.

Bronze sculptures were ubiquitous in the Hellenistic world. Once thousands of statues stood in the temple precincts, theaters, and other public spaces of cities, major and minor. Pliny (Natural History 34.30, citing L. Piso) describes how in 158 BCE the censors decided to remove all the statues from the Forum Romanum erected without official permission, an action that suggests there may have been a glut of them set up by individuals and professional groups. (The portrait statue of Aule Metele, or Arringatore, from Florence on view here invokes these proliferating sculptures.) Most bronzes were lost to later destruction, primarily melted down to make jewelry, coins, and weaponry. Natural disasters protected some, and the large number discovered underwater indicates regular commercial transit and a thriving art market similar to the modern era’s, with rich collectors, savvy patrons, and dealers. More than half a dozen works in the show were stumbled upon in the sea, with two discoveries as recent as 2004. Today only two hundred large-scale bronzes of the Hellenistic era survive, and Power and Pathos assembles some fifty of them in one place, including loans from thirty-four museums in twelve countries, many national treasures. Seeing them together gives a fleeting sense of what residents of ancient cities experienced everyday. It is the first show of its kind, and will probably be the last in our lifetimes.

Peter J. Holliday

Professor, History of Art and Classical Archaeology, California State University, Long Beach