- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Environmental Art at the 56th Venice Biennale

The 2015 Venice Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor, focuses on the unpredictability and volatility of our historical moment, or what in another context Ulrich Beck calls the “risk society” (Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, London: Sage, 1992). As Michelle Kuo explains in an interview with Enwezor: “That is when the unintended side effects of modernization—technological, ecological—seem to be overwhelming the systems devised to contain them, creating entirely new crises and instabilities” (Michelle Kuo, “Global Entry: Okwui Enwezor Talks with Michelle Kuo about the 56th Venice Biennale,” Artforum 53, no. 9, [May 2015]: 85). Some of the more challenging pieces in the biennial as a whole that I highlight in this review respond to Beck’s environmental concerns about modernization and articulate globally significant but often overlooked intersections between environmentalism and sustainability, and between decolonizing strategies and representational structures. In so doing these artists in the exhibition are calling forth new forms of representation that seek to record and act on the precarious world we inhabit and come up with multiple ways of imagining—in the words of Enwezor’s title for the show—“all the world’s futures.”

From the national pavilions in the Giardini, one of the much-publicized standout installations is by Australian artist Fiona Hall. Its title, Wrong Way Time (2015), suggests her pessimistic outlook regarding the looming threat from climate change and our deleterious role in the state of various species. Her installation reworks the historical cabinet of curiosities from an environmentalist perspective to reveal how human-induced transformations in the physical environment causing climate change are irrevocably altering our relationship toward the wilderness and wildlife and disrupting our ordinary ways of seeing and knowing.

This stunning display is one of the best examples of the new forms of art that are coming into being in the age of the Anthropocene. Hall’s piece as a whole is difficult to take in at once because of the vast array of objects and sites it includes from around the world, such as the Kermadec Trench in the South Pacific with its endangered marine creatures or her intimate attraction to the Pitjantjatjara’s Mamu in Australia. Each object in Wrong Way Time can be unraveled in detail, but its greatest strength lies both in the particulars and its overall reflexive approach toward late modernity and the way it embodies a form of “eco-cosmopolitanism” that brings individuals and groups together into planetary “imagined communities” of both the human and the nonhuman kind” (Ursula Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, 61).

Another notable installation is Lina Selander in the Swedish pavilion. Lenin’s Lamp Glows in the Peasant’s Hut (2011) deals with the 1986 nuclear disaster in Chernobyl, Ukraine, and the present and future force of that disaster’s ongoing percolations. This black-and–white, silent film installation draws from specific methods of Soviet montage in the early years of cinema. She re-edits sequences from Dziga Vertov’s 1928 film The Eleventh Year, celebrating the technologies of the future from the first decade of the Soviet state, with contemporary footage that details the failure of that dream. In this way, Salander turns the history of photography and cinema into an archive of knowledge and disappearances. By virtue of this simple juxtaposition, her montage moves away from a celebratory modernity of political utopias from the early twentieth century that Vertov’s film documents. Instead, it exemplifies a more reflexive modernity that focuses on the environmental impact of human, technical, and industrial actions and disasters like Chernobyl in terms of conditions where health, safety, and environmental regulations were absent, lax, or poorly enforced.

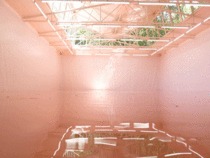

In the Swiss Pavilion, Pamela Rosenkranz also makes her focus the high cost of modernity and its visual inscription in relation to environmental themes. Her installation, Our Product (2015), features a sublime, empty pool of liquid plastics the color of a standardized northern European pink skin tone. The materials from which Rosenkranz’s work was made include silicone, Neotene, Viagra, Bionin, Necrion, and more. The pink pool at the center of the pavilion seems calm and peaceful with its accompanying synthetic sound of water and a scent that evokes the smell of fresh baby skin. But the soothing aspect of her highly artificial installation is transformed by the unsettling feelings it produces about the ways that race, gender, and class permeate the drug, cosmetic, and advertising industries.

Environmental concerns in relation to representational practices are put into a wider historical context in All the World’s Futures. Take, for example, Vertigo Sea (2015), a compelling three-channel film installation by British artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah. What makes Akomfrah’s large-scale work so memorable is the way it uses both archival materials and newly shot footage to bring into view in a highly aesthetic way the imperceptible history of the violence of the oceans. Akomfrah has viewers witness how the history of industrial whaling starting from the seventeenth century onwards is connected to the history of colonialism and slavery. Obtaining the oil produced from the blubber of whales was the reason for the first oil rush and led to the extinction of certain species of whales in the Arctic as early as the seventeenth century. The many graphic and often spectacular archival cinematic images of whales being slaughtered for food and fuel make for grim viewing. Viewers do not witness the same violence enacted directly on slaves, yet a similar sadistic cruelty comes across from the soundtrack of dialogue taken from nineteenth-century texts on the slave trade. The documentary still images are of adults and children tossed overboard who were deemed unfit, and the newly shot footage shows drowned black bodies that turned up on shore. A strong component of Akomfrah’s work is the experience of viewing these disturbing juxtapositions of human and animal drownings that are made to evoke previous historical eras and mass deaths. Both deal with wide-scale killings that were not seen or felt by most, and each happened in a remote location on the oceans. Afkomfrah’s film stages the ocean as a zone of commerce as it asks who bears the social authority of witnessing in this site of exchange and massacre.

Intersections between environmentalism and decolonization strategies is also an issue in Chantal Akerman’s disturbing multi-channel video installation titled NOW (2015). Her installation features eight screens of footage that she filmed from a car driving in a geographically remote, desert-like countryside at high speed with gunshots on the soundtrack. One would be tempted to suggest that this takes place in Israel, given the images of the landscape and the life-threatening emergency evoked. However, Ackerman does not leave any direct clues except that what appears to be an “empty” landscape is clearly inhabited and that the gunshots suggest that the emptiness could be the result of an effort of depopulation that has failed. The wide-angled images of the “empty” landscapes on the monitors contrast with the final one at the end of another vacant but different kind of lush and habitable landscape devoid of violence and gunshots but disturbingly artificial and implausible. Neither choice seems viable. The impossibility of a future in either space mirrors the environmental dead end evoked by other artists, and it is hard to separate Akerman’s grim thoughts in her last installation from her own unexpected death while the biennial was still ongoing.

If aesthetic representations of landscapes and oceanscapes once seemed to offer a stable and idealized alternative to the world of capitalist modernity, the artists discussed here are increasingly seeking to document the ways in which fossil fuels are shifting such perceptions. These artists are interested in the intersection between environmentalism and representational practices that deal with the movements of people, nonhuman animals, plants, and landscape that are changing in unprecedented ways due to environmental degradation and climate change. Consequently, for some of these artists, nature is no longer a thing apart to be manipulated and exploited at a safe remove. It is now integral to a larger universe of instability, technological breakdown, social disruption, and suffering that is happening on a planetary scale.

Lisa E. Bloom

Research Scholar; University of California, Los Angeles; Center for the Study of Women