- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

“How many minutes would you invest in looking at a particularly striking photograph?” I asked this of my History of Photography students last year, and the response came not in minutes but in seconds. They largely used Instagram as their default experience: “six seconds” answered one of the more thoughtful students. “No,” argued another, “maybe three seconds, if it’s attached to text on a blog.”

Thus the understandable motivation of undertaking an exhibition like Photo-Poetics: An Anthology, particularly its passionate advocacy of investing time in looking closely at photographs. In the opening wall text of her Guggenheim Museum exhibition of ten contemporary photographers, curator Jennifer Blessing enticingly stated: “Each artist contemplates the nature, traditions, and magic of photography at a moment when the medium seems poised to evaporate into digital oblivion.” As far as executing this thesis and realizing the criteria, some individuals and groupings were significantly more compelling than others.

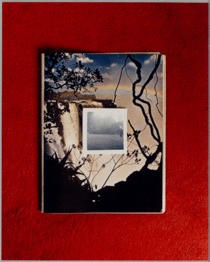

Leslie Hewitt’s works were the first encountered as the show commenced in the second floor tower. The emphasis in Hewitt’s selection was clearly the series Riffs on Real Time (2006–9), which displayed snapshots upon printed matter upon hardwood floors or carpeting, a seeming attempt to emphasize variegated materiality. More alluring was the 2009 work Untitled (Seems to Be Necessary). Her success at creating a suite of highly differentiated tactile surfaces—e.g., curtain-wood-photographs-piece of fruit—was a stunning twenty-first-century take on Svetlana Alpers’s canonical 1983 book, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), and a notable extension of a trajectory dating back to seventeenth-century Dutch still-life traditions that demanded close looking by their viewers. Hewitt’s contemporaneity was especially pronounced in the way the photograph was laid on the floor and propped against the wall, protruding into the viewer’s space. It thus created a sculptural “experience” rather than a two-dimensional encounter with flatness, at a moment when many current museum viewers seem to long more for experiences than for straightforward viewings.

Also eye-catching on the second floor was Claudia Angelmaier’s take on Albrecht Dürer’s rabbit study, entitled Hase (2004). It was fascinating to see the variation in reproduction color and quality of the same art-historical image in various textbooks. On the other hand, it also felt like a type of exercise that has been realized before, notably in various series by the artist Hans-Peter Feldmann, such as 9/12 Front Page (2001). More wholly original in this section was the video work Les Goddesses (2011) by Moyra Davey. This was a fairly long video piece (sixty-one minutes) that many would likely relish seeing repeatedly. In her Upper West Side apartment, Davey dictates theories, thoughts, and memories over languorous images of rooms, photographs, and, most seductively, books in bookcases. Of particular interest to her are those related to Romanticism in different forms, including ones by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the Wollstonecraft-Shelley families. It was a revelation to be reminded of the sheer pleasure of looking at the spines of books in a bookcase: what it feels like to touch them and think of the memories their physical presence elicits of what it was like to read them. And on a deeper level, how certain books connect up with one’s own personal memories. Davey’s example of this near-universal sensation is to parallel the story of Mary Wollstonecraft’s daughters, including Mary Shelley, with Davey’s own relationship with her sisters. The experience of watching Davey travel widely in her mind while not leaving her apartment was a perfect realization of the “magic” of imagery to which Blessing referred in her wall text.

Another sensualized video experience revealed itself on the fourth floor, the next stop in this broken-up installation, and the strongest section of the exhibition. Erin Shirreff’s UN 2010 (2010) made the viewer—depending on the moment of entry into the room—feel bathed in the same hazy gray and blues as those bathing the landmark building in a faux twilight. It is explained that several photographs of the building were manipulated and “choreographed” to create what appears to be an unfurling diary of the building and the world around it at different times. Although Blessing is correct to note in the catalogue that it recalls the “atmospheric scale of a nineteenth-century painting of a sublime landscape,” it strikes me as overly formalistic to also describe the United Nations building’s geometric form as a “perpendicular echo of the flat projection” (103). That is precisely the kind of analysis that compromises the “magic” the video otherwise achieves. Likewise magical were Sara VanDerBeek’s Crepuscule prints (2015), ghostly abstractions scarcely emerging from a white background, hovering between life and death like the well-documented near-death experiences of going “into the light.”

Erica Baum’s Naked Eye series (2008–present) provided yet another unique way within the exhibition to think about the interrelationship between books, films, and photography. These were cheap paperbacks, mostly novelizations of movies or tie-ins, photographed with a chunk of their leaves showing in striated lines, and eerily familiar-yet-hard-to-place film stills hovering within. One gets the sense that in her selection Blessing longed for the demands that books make upon their readers; there is no choice but to read. And if one believes that photographs now can only be flipped or swiped through? No, these photo-poets are to be read.

The fifth and final floor was the most underwhelming. It felt very much like John Baldessari redux, dominated by found-photograph constructions and images mimicking the film-still style, although Anne Collier’s Crying (2005) with Ingrid Bergman’s face on one of several album covers stacked on a minimalist black-and-white grid stopped me in my tracks. The entry on this piece in the exhibition catalogue was one of Blessing’s most evocative, with a beautiful passage about Crying embodying a “kind of deflected self-portraiture” (44).

Taken together, the works in Photo-Poetics created a striking and in some ways oppositional pendent to Carol Squires’s International Center of Photography exhibition What Is a Photograph? from 2014 (click here for review). That exhibition also attempted to reclaim the “materiality” of photography through an overview of output since the 1980s. In Squiers’s case, the opening wall text posited that conceptualism rejected “the imaginative possibilities of photography,” and she was attempting to reclaim the materiality of the medium from it. In the Photo-Poetics wall text, Blessing described her artists as drawing on the history of conceptual art while being “fascinated by the material manifestations of photography . . . as objects.” So which conceptualist legacy now dominates? One that values materiality or does not? In Squiers’s show, she claimed the materiality of her selections revolted against the conceptualist legacy seen in the Pictures Generation. In Blessing’s show, she claimed the materiality sprung from conceptualism’s influence.

There appears to be a tug-of-war over how conceptualism will be overarchingly defined going forward: that of Jan Dibbets—more material-based—or that which is seen in the deadpan Pictures. Interestingly, despite Blessing’s stated homages to Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, and others, the works in Photo-Poetics that stray furthest from the Pictures were the most striking (Hewitt, Davey, Shirreff). In the wake of these exhibitions, it may be time to revisit the history of conceptualism in photography, as Matthew Witkovsky did with his exhibition Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph, 1964–1977 (2012). Baldessari has a central role in the accompanying catalogue (Matthew Witkovsky, ed., Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph, 1964–1977, exh. cat., Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), and he is one of the more compelling candidates who can bring together these two impulses of materiality and the deadpan, rather than set them at odds.

Blessing articulated her motivations toward the end of her introductory wall text: “The works in this exhibition, rich with detail, reward close and prolonged regard; they ask for a mode of looking, in real time, that is closer to reading than the cursory scanning fostered by the clicking and swiping functionalities of smartphones and social media.” She is, in many cases in Photo-Poetics, correct in this assessment. One hopes a place for such looking remains, given the millennial habits of viewing described above.

Vanessa Rocco

Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities, Southern New Hampshire University