- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

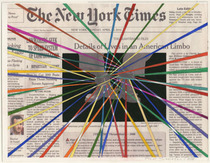

Fred Tomaselli’s solo exhibition The Times at the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA) is the New York-based artist’s first West Coast show. The exhibition is also a homecoming for the artist, who grew up in the neighboring city of Santa Ana. Before traveling to Orange County, The Times spent four months at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. The idea for these two exhibitions came from James Cohan Gallery’s debut spring 2014 show, entitled Fred Tomaselli: Current Events. As the artist’s gallery representation, James Cohan dedicated Current Events to exploratory artworks that Tomaselli colloquially calls capriccetti. As the catalogue interview between Lawrence Weschler and Tomaselli notes, the term signifies whimsical and short-lived, yet ambitious, sideline projects. The relationship between Tomaselli’s capriccetti artworks in The Times and his larger body of work is explored at OCMA’s instantiation, curated by Dan Cameron. The conceptual and visual cohesion of the exhibition hinges on the dynamic interplay of the artist’s recently developed work and his longer-term artistic engagements.

The exhibition consists of three individual galleries that flank the left side of the museum’s open-concept floor plan. Tomaselli’s solo show bleeds into OCMA’s other concurrent exhibitions Misappropriations: New Acquisitions and Alien She (click here for review). The entrance to The Times features only one of the show’s namesake New York Times cover collages, entitled Guilty (2005). This artwork’s placement in the exhibition is important because it is the inspiration for all of the other Times covers featured in the next two galleries. Guilty is an archival inkjet printed on watercolor paper. Inspired by a Times cover image from March 16, 2005, Tomaselli manipulates the photograph of Bernie Ebbers’s “perp walk” after being found guilty of fraud. In the image, a wall of news-media photographers and paparazzi bombard a confounded Ebbers and his wife, who solemnly clutch hands as they exit a courthouse building. Tomaselli reenvisions the scene using gouache paint, leaving certain elements of the original photographic composition either intact or completely reworked. In Guilty, Ebbers’s face becomes a mask of red bursts of color mixed with a background of saturated yellow lines and dots. While his suit remains untouched, Ebbers’s face blends into a new background consisting of a warm palette of delicate flowers. His wife Kristie’s right eye is transformed into a yellow sunburst, and a similar luminescence encircles the figures’ clasped hands.

The visual impact of Guilty’s “tampering” of the Times cover reorients a scene of capitalistic greed into one of almost iconic reverence. Kristie Ebbers’s sunburst eye looks steadfast as her husband’s obscured face hides in the background, as if in shame. The main focal point in this work is the conjoining hands rimmed with a halo. As recounted in his interview with Weschler, when Tomaselli first saw the original cover, he had a different vision from the one presented by the newspaper photograph. He glimpsed a tender touch between two individuals—a representation of human vulnerability even in the most morally questionable situations. This interpretation of Guilty explicitly mimics the artistic composition of Masaccio’s fresco The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (ca. 1425), which Tomaselli uses as an alternative portrait for Ebbers and his wife.

This theme of portraiture is one purposely examined by The Times. Accompanying Guilty in this gallery are three strikingly different earlier works that visually experiment with traditional modes of portrait making: Portrait of Jim and Vivian (1991), Portrait of Paul (1992), and All the Bands I Can Remember Seeing and All the Extinct Vertebrates Since 1492 (1990). Sheets of black paper serve as the ground for white-colored pencil sketches of constellations of information regarding each portrait’s subject. The networks of white line plot a chaotic matrix of self-identifiers that seek to capture either the basic architecture of a person’s personality, the movement of chemical substances within a human body after they are consumed, or the capacity of memory to visualize a historical moment. What links Guilty to these early works is their positioning of other realities, which exist on top of, or underneath, the New York Times’s popular adage, “all the news that’s fit to print.” The trace of the original image, be it the actual newspaper or person “sitting” for the portrait, is a contested background for Tomaselli to use his collage and multi-media technique to creatively manipulate the realities expressed by various forms of visual information.

In the second gallery, Tomaselli’s more well-known large resin combines accompany his newspaper covers, creating a kind of total environment. The intricately painted Times covers, when viewed from afar, produce an effect in which colors, images, and lines blend together in a visual cacophony. The resin combines provoke another dynamic. Although from far away these works look similar to the Times covers, as one approaches the images, they break down into a swirling mass of leaves, psychotropic pills, newspaper, magazine, and paint suspended in thick, reflective resin that captures bits of consumer materials which are meant to be momentary fragments of modern life. The newspapers, amassed tightly together on the gallery walls, convey the accumulation of the daily news, which is instantly made obsolete the next day. The ability for these works to substitute the information already embedded within mainstream ephemeral objects with new meaning is directly related to the alternative portraiture surveyed in the first gallery.

The third, and last, gallery space is more forthcoming about this connection. Residing on one of the walls are two artworks, one of newspaper and one of resin, placed side-by-side. This curatorial choice aligns more squarely with a traditional display of artworks, something very different from the clustered kaleidoscope effect of the previous gallery. These works are respectively titled Nov. 19, 2013 (2014), displayed at left, and After Nov. 19, 2013 (2014), displayed at right. Each contains an image of a red cardinal sitting near the picture plane’s foreground. The avian figure from the mid-November 2013 cover sits atop a landscape left relatively unmarked by Tomaselli. The caption of the newspaper image explains that this is the leveled ground of a town destroyed by a tornado. Mimicking the vortex of this weather phenomenon, the head of the cardinal explodes in an inverted cone of eye-like circles, each with different color combinations. The resin work made “after” this cover visualizes a similar scene. The cardinal in this larger piece occupies the same position, but with the landscape behind it changed. The background is not the aerial view of a destroyed housed, but rather an idyllic depiction of rolling hills vanishing into a distant tinge of orange, which may be a sunrise or sunset. The empty space above the horizon line is thick and dark, yet populated by bright white dots recalling a starry night or early dawn sky.

Looking at Nov. 19, 2013 and After Nov. 19, 2013 like this indicates that each combine featured in the exhibition may have a corresponding newspaper collage, just as these works combine the familiar and otherworldly. Tomaselli blends multiple levels of information—the mainstream newsreel from a particular day, the artist’s own reflections on a media story, and the viewer’s reception of both—to produce a quixotic vision for representations of reality: its events, visual systems, collective memories, and material accumulation. Tomaselli notes in his interview with Weschler that the conceptual framing for his Times artworks stems from a theoretical engagement with John Berger’s own “against the grain” use of 1970s-era badedas advertisements from Britain’s Sunday Times Magazine in Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin, 1972). Part of what makes Tomaselli’s alternative newspaper and resin artworks successful at garnering a critique of the reality structured by media representation is their ability to distort this actuality by making objects and persons, gauche and news photography, entirely interchangeable.

Jessica Ziegenfuss

PhD candidate, Visual Studies, University of California, Irvine