- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

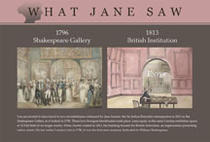

Art history would seem to be a discipline that could and should generate digital visualization projects—if only for the simple reason that the objects of study are already and easily found in digitized form. As evidenced by the number of workshops and conferences and the general buzz on the subject, the attention given to this type of project has intensified in the past few years; but there are still very few operational sites in the field. A close consideration of one such site, “What Jane Saw” (visited May 2015), raises important questions facing project developers and users of digital art-history resources. What can a digital project provide that print scholarship cannot accomplish? How can digital projects best utilize available platforms and software programs instead of writing new code with limited application and great financial expense? How does the site acknowledge historical uncertainty and critical interpretation? Who is the intended user: a specialist, a student, a web surfer—or all three? How do we critically evaluate digital projects, which often receive updates and refinements and, therefore, rarely exist as fixed and final?

“What Jane Saw” digitally reconstructs the retrospective exhibition of paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds held in 1813 at the British Institution in Pall Mall, London. Among the many visitors drawn to the three-month event was the British writer Jane Austen, who made specific mention in a letter of her plans to visit the exhibition, and, as a result, provides the organizational frame and personalizing perspective for the site. Developed by Janine Barchas, professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin, the site includes three-dimensional visualizations of the three exhibition rooms with hypothetical reconstructions of the hung paintings, a digital reproduction of the Catalogue of Pictures originally produced in conjunction with the exhibition (and linked to descriptions of the artworks), and an “About WJS” section in which Barchas discusses the historical background and shares her rationale for developing the site in its current form. The navigable reconstructed exhibition space allows users to click on the individual paintings to see in a pop-up box the dimensions of the picture, a descriptive summary of the painting’s subject, and reproductions of engraved copies.

When launched on May 24, 2013 (exactly two hundred years to the day of Austen’s reported visit to the exhibition), Barchas’s site received immediate attention from several news outlets, including the New York Times and the Guardian, most likely because of Austen’s appeal to contemporary audiences. But the site also positions itself as a highly accessible repository of information that is aimed toward a more general and less academic audience. The “Q&A” format for the “About WJS” section and the brief and, at times, cursory descriptions of the pictures (and their omission of important information such as execution dates) suggest that Barchas’s main objective for the site was public outreach of some kind, whether through teaching or, following Barchas’s own “celebrity-centric” approach to Austen in her print publications, to make history relevant to the general public. Furthermore, the site presents one scholar’s perspectives and conclusions, and was not created—in this phase, at least—to be a tool that users could customize to their own research interests. The site gives an answer to a specific question (“What does Barchas think that Jane saw?”) and cannot readily be manipulated to answer new and different ones.

Developers of digital humanities projects are faced from the outset of their undertaking with this distinction between archive and tool, as well as a need to understand the implications of their decision to follow one path or to pursue both. For Barchas’s site, the goal of recreating a specific exhibition at a specific historical moment led to a singular reconstruction of the hanging of pictures based on her historical understanding of aesthetic choices and social standing. But, as she shared in an essay about the site that was published in ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640–1830, Barchas considered multiple possible hangings before arriving at the site’s current arrangement (Janine Barchas, “Digitally Reconstructing the Reynolds Retrospective Attended by Jane Austen in 1813: A Report on E-Work-in-Progress,” ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640–1830 2, no. 1 [March 2012]: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/abo/vol2/iss1/13). Including these versions on the site itself—or allowing users to manipulate the hangings themselves— would have deepened its use value, without changing its archival contribution, as well as raised bigger questions within the site itself about methods of historical reconstruction for an ephemeral event. The reproductions of the pictures in relative proportion to one another on scaled walls allow a unique and valuable opportunity to explore possible display practices through multiple visualizations rather than determine those practices through general inferences and painted representations of later exhibitions at the British Institution. Barchas’s reconstruction might be the historically correct one, but a more historically instructive and elucidating method would have been to provide specific reasons—other than general aesthetic ones—for including or excluding a given reconstruction. What, for example, are the precedents for hanging in alignment across the room the portraits of the king and queen? How would the privileging on the wall of the portrait of Sarah Siddons have affected the nature and experience of the exhibition? What, if any, formal correspondences between different pictures possibly governed the hanging of a wall or of the entire exhibition?

Barchas’s commitment to a specific reconstruction relates to the challenge of visualizing uncertainty in digital humanities projects. In printed scholarly publications, unacknowledged gaps in the historical record traditionally are a sign of poor scholarship. Consequently, the field of art history has found acceptable ways to indicate lacunae in books, articles, and conference papers. Digital tools often develop precisely from and around those incomplete spaces involving the unknown and the inconclusive. On the one hand, those projects which involve incomplete historical records—not unlike the lack of information about picture placement in “What Jane Saw”—often benefit most from visualization of some kind, whether virtual reconstructions, or mapping, or some other method. Patterns in known and unknown information often are easier to see all at once, rather than being imagined from narrative accounts. On the other hand, unknowns and gaps are often difficult to acknowledge in data entry and capture in software programming. There is not yet an accepted “language” for lacunae in digital projects. Because of the complexity in signifying absences, digital humanities projects oftentimes have to relegate these decisions to later phases of development in an effort to produce a useable site with the available resources.

One of the great strengths of “What Jane Saw” is how the project leverages widely available platforms to develop the site from the programming side. The virtual reconstructions of the exhibition space were developed through SketchUp and given aesthetic doctoring to resemble a Regency-era interior by the programming team from the Liberal Arts Development Studio at the University of Texas at Austin. The in-house group also assisted with providing architectonic specificity to a digital collection of artworks, which added a layer of complexity to the kinds of digital collections that already are possible to build with the web-publishing platform Omeka. Barchas’s site clearly involved more work than simply bundling these two familiar digital resources—such as her inclusion of the pop-up boxes and the option of switching easily between color and black-and-white reproductions—but the site functions as a great exemplar of a digital humanities project that builds on the shoulders of the known digital giants rather than embarks on the daunting task of reinventing the wheel. This should hopefully encourage other humanities scholars to do the same and not postpone a project because of a small budget.

Another inspiring aspect of “What Jane Saw” is that it reinforces how interdisciplinary and collaborative research—long aspired to, but rarely accomplished in print scholarship—potentially finds a favorable medium in digital projects. The pairing of art history and literature in the site through the joining of the historic exhibition and one of its famous literary visitors facilitates an approach to material that had been available and accessible since the publication of the exhibition catalogue, but that had not yet been approached from this perspective. The intersection of art and literature happens, though, not exactly through or within the virtual space, but through the text accompanying the pop-up reproductions, within which Barchas shares points of connection between the depicted subjects and Austen’s own writings on the level of content. A painting with gypsies (No. 12, North Room), for example, prompts Barchas to note which of Austen’s books references the same subject. The result is a highly general and not entirely useful entry for scholars of English literature or art history; however, the biographical information and suggested readings provide a helpful starting point for nonspecialist site visitors. For identifications and information on the dimensions of the artworks Barchas relies primarily on David Manning’s Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), but she limits her engagement with broader art-historical topics relevant to Reynolds’s pictures, such as emulation and influence, especially as they relate to portraiture—the most prominent genre in the exhibition. These issues are not exactly identical with Barchas’s interest in enlivening Austen’s texts and Reynolds’s pictures as examples of celebrity culture, yet these concerns belong in the conversation about how nineteenth-century society constructed fame, regardless of Barchas’s intended website audience or user population.

Nearly two years old, the site still stands out as one of the few useable and fully developed digital projects that was produced by an academic and that has connections to the discipline of art history. This is a significant accomplishment, which is made more impressive given that even fewer models existed for “What Jane Saw” when Barchas undertook the project. Developers of digital art history projects would be well advised to follow Barchas’s model by starting with a clearly defined and potentially flexible research question. The challenge after that, as demonstrated by “What Jane Saw,” is determining and clarifying the identity of the site based on its function (archive, tool, and/or amusement?) and its target user group (general public, student, and/or specialist?). The great opportunity of digital projects is their dissolution of hierarchical categories by being available to all; the difficulty is being able to address and serve everyone while also maintaining a scholarly commitment to the historical material.

Jodi Cranston

Professor, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Boston University