- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Just beyond the main galleries of the Art of the Americas Building at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is a small room featuring eight large painting by Sam Doyle (1906–1985). The paintings are created from everyday materials, making them distinct from the oil paintings, art deco objects, and mid-century modern furniture in the neighboring galleries. Using house paint on found wood and metal to create figurative and text-based paintings, Doyle portrayed famous African American entertainers and athletes as well as legendary figures, friends, and family from his Gullah birthplace on St. Helena Island, South Carolina. The intimate grouping of paintings was selected for exhibition by Franklin Sirmans, Terri and Michael Smooke Department Head and Curator of Contemporary Art, LACMA, from the Gordon W. Bailey collection. The exhibition is the result of Sirmans’s interest in Doyle and artists associated with him, some of whom were featured in the nearly year-long 2013 exhibition Soul Stirring: African American Self-Taught Artists from the South at the California African American Museum. This solo exhibition offers an opportunity for further study of the characters Doyle immortalized. Most of the artworks serve both as portraits and genre paintings by offering text around his subjects denoting their remarkable accomplishments.

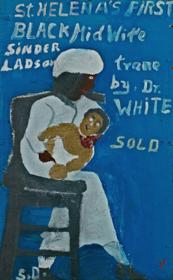

In First Black Midwife (1978–83) Doyle depicts a seated woman in a gleaming white uniform. Floating above the woman is text identifying her as “St. Helena’s First Black Midwife,” who was trained by one “Dr. White.” In fact the woman is Doyle’s grandmother Lucinda “Sinder” Ladson presented heroically with a chunky, wide-eyed baby cradled in her arms. Doyle’s affection for his grandmother comes through in earnest. The painting’s surface has been reworked and shows a palimpsest trace of previous iterations of Ladson’s form, marking the time Doyle spent getting the homage just right. The simple and immediate clarity of information combined with the maternal subject matter creates a feeling of intimacy. Further, his respect for her is literally marked on the painting. On the bottom left edge he painted his initials in bold white letters, and wrote the word “Sold” beside Ladson’s left hand signaling to potential collectors that the work was not available for sale.

Although musician Ray Charles was not a family member, Doyle’s painting Rey (1970–83) also relays admiration for his subject. In a formal white shirt and dark blue pants, Charles appears dwarfed in front of an oversized piano that he reaches up to play. Composed on a square sheet of pockmarked, corrugated metal, Rey could easily double as an advertisement on a nightclub for a coming attraction. At the top of the composition is an orange square with “REY” written in white like a neon sign. Though it may only be a misspelling of the name Ray, “rey” is Spanish for “king” and offers a second meaning that monumentalizes the significance of this musical legend for Doyle and fans worldwide.

Likewise, in Jake, Our Best (1978–83) Doyle imagines another national figure, baseball great Jackie Robinson, with pride and celebration. With baseball in hand, cap turned backward, and a fierce expression, Robinson stands ready to play for his team and his people. His cap echoes that of Ladson, the midwife across the room who nurtures the next generation. Along with Rey, these heroes become singular icons in flat yet colorful backgrounds—giant trading cards for the best of Black America.

Doyle’s work unapologetically takes up visual and physical space—standing as testimony to the life he lived and the people he held in high esteem. Even in this small selection of work, it is possible to imagine the much larger indexing project that Doyle was building. The series is a celebration of people painted with joy. His use of bright colors and choice of large-scale materials seem to radiate the artist’s optimism that the people imaged would never be forgotten.

His paintings also demonstrate regard for his viewing audience, an increasing number of visitors who came to see his art on display in his yard—called the St. Helena Out Door Art Gallery—throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In Visitors Sign (1970–85), the largest painting in the exhibition, Doyle listed the names of cities and countries from which his visiting public originated. Written loosely in columns over a thick coat of white paint on wood, the sign shows his interest in meeting the people who were attracted to his work and aware of his growing fame.

Located in the Special Installation Gallery, Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye informs visitors of what else was going on in modern art besides the more or less expected selection from a great collection of twentieth-century art. At LACMA the Doyle exhibition interrupts the standard narrative of modernist art history and widens a thematic timeline of significant objects. The exhibition’s title wall text states that painters Jean-Michel Basquiat and Ed Ruscha are among Doyle’s collectors—a statement that reminds viewers of the interconnectedness of canonical artists and inspired folk artists who share the task of expressing their unique visions and reflecting a common culture back to the world. The exchange of ideas within Doyle’s art and career helps shift the focus away from an autobiographical narrative that limits the discourse on folk artists. If sociologist Gary Alan Fine is correct that “the assumption of unmediated communication legitimates the works” of folk artists, a different approach to Doyle’s work must be taken (Gary Alan Fine, “Crafting Authenticity: The Validation of Identity in Self-Taught Art,” Theory and Society 32, no. 2 [April 2003]: 161). This exhibition suggests that viewers consider Doyle as an artist outside of the folk-art myths of authenticity and purity in order to dissolve the fraudulent boundary that groups all folk artists together as other while setting them aside at a collective distance from the mainstream.

Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye can be considered alongside the recent exhibition When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the America South, curated by Thomas J. Lax at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2014. Lax’s exhibition also offered an interventionist approach to reconsidering folk art by presenting it with art by formally trained artists. Untitled: The Art of James Castle at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (2014–15) stepped in the direction of these innovations; its press release states, “This exhibition seeks to move beyond such biography, to appreciate the remarkable quality of Castle’s vision, and to question how the works themselves can elucidate the world of one of the most enigmatic American artists of the twentieth century.” These exhibitions and more are part of an expanding understanding of folk art that has been in need of rejuvenation. The strength of Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye is that it focuses on one artist through multiple works and is therefore able to display the diversity and development within a single oeuvre.

Bridget R. Cooks

Associate Professor, Department of African American Studies and Department of Art History, University of California, Irvine