- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

“We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendour or such beauty and we are at a loss how to describe it. We only know that God dwells there among men.”

—Description by Russian visitors to the Byzantine Church of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople/Istanbul. The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text, eds. and trans., Samuel H. Cross and Olgerd Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1953, 110–11.

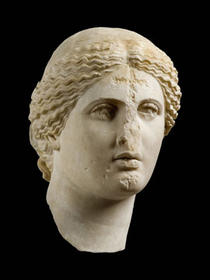

A clumsy cross etched into the forehead of a serene sculpted head of Aphrodite; a small amulet case that could just as easily have held Christian or “pagan” apotropaic scrolls; Byzantine jewelry with Arabic-inspired inscriptions—all of these works testify to the engrossing conundrums posed by the exhibition Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, which brings to the United States exquisite examples of art from a period only meagerly represented in most major American museums’ permanent collections. Organized by Greece’s Ministry of Culture and Sports with assistance from the Benaki Museum in Athens, there are a remarkable range of contributing institutions. While the weight of the material derives from well-known collections such as the Benaki or Thessaloniki’s Museum of Byzantine Culture, others likely unknown to American audiences, such as Metsovo’s Baron Michael Tossizza Foundation, also sent items.

First presented at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and then at both the Getty Villa and Getty Center, the layout varied substantially between its East and West Coast versions, and this review focuses on the iteration in Malibu. (The Art Institute of Chicago exhibition includes about a third of the objects.) Heaven and Earth offers not only a historic opportunity to view artworks never seen before in the United States, but also marks a welcome rapprochement in the relations of the Getty with Greece.

If its icons are often imagined as defining Byzantine visual culture in the histories of Western art, then the opening piece, the lyrically classical fourth-century Bellerophon Killing the Chimera, will come as a surprise to many viewers. The intermingling across the realms of the Christian and pagan that have been long explored in the scholarship of the field are adduced in its label, which ties the equestrian imagery with a later, Christian work, the Saint George icon from Patmos (in the catalogue, but regrettably omitted from the exhibition). Nearby, however, the label for the ivory plaques rendering the life of Achilles omits any reference to the manuscript of the Iliad on display nearby, and, because of the exhibition’s scope, making such connections for viewers would seem particularly useful.

The first-century Head of Aphrodite, with a cross later incised into its forehead, also poses intractable and endlessly absorbing questions. The label hints that the Christian iconoclasm gave the goddess “a new religious meaning,” and the catalogue entry by Maria Salta delves deeper into the challenges of articulating precisely such mutable connotations (60). Getty Villa curator Mary Louise Hart and her team’s careful integration of the label material with the catalogue is evident in such instances. The shows’ origin in Greek collections offers a decentering of perspectives on the way Byzantine art history is habitually oriented around artistic production of the empire’s capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul). Thus Heaven and Earth undercuts prevalent assumptions about its subject, giving the viewer ample chances to question what (or where) defines Byzantine art.

The contrast of the Getty exhibition with the recent one at the Menil Collection in Houston, Byzantine Things in the World (May 3–August 18, 2013), is striking. The meticulously curated Menil show gave a series of thought-provoking juxtapositions of Byzantine with modern and contemporary works, so by design the Menil exhibition prodded the viewer to understand the medieval objects outside of a normative narrative of scholarly art history of this period. In some ways the Menil project can be seen as allied with the “new materiality” in art history, disrupting viewing practices centered on identifying iconography and such matters. The Getty installation’s partly ahistorical framing also deviates from the path set by other exhibitions of Byzantine art in recent memory, such as the landmark Metropolitan Museum of Art series that began with the Age of Spirituality in 1977. Sometimes the Getty’s thematic and chronological links can be tenuous. Although the first room is defined by period, the rest is arrayed by categories such as the “Spiritual Life” or “Crosscurrents.” The second, and largest, room of the exhibition contains its best-known works, the fourteenth-century panel of the Archangel Michael as well as the twelfth-century double-sided icon of the Virgin and the Man of Sorrows that came to wider renown through Hans Belting’s remarkable studies. While the initial room offers a compelling exploration of its Late Antique contents, the reasoning that informs the Getty’s organization of the rest of the material is not always apparent. It is hard to know what connections a visitor would make from perusing the following sequence of items encountered walking through the exhibition’s main hall: a late Byzantine icon of the Transfiguration, an enormous photograph of the interior of the Middle Byzantine Church of Hosios Loukas, and a multimedia display of Byzantine coinage adjacent to a vitrine with a Gospel Book.

The Getty Center houses a tightly organized ancillary display that juxtaposes several of the manuscripts on loan from Greece with counterparts from the Getty’s permanent collection. The Getty’s Ethiopian Gospel Book (Ms. 105) faces off against the National Library of Greece’s Cod. 57—four centuries separate the two evangelist portraits with similar compositions, enlivened by radically different aesthetic sensibilities. Equally provocative questions are asked about the transmission and meaning of the written text by showing the purple-hued Gospel lectionary, made in the Rhine-Meuse region, early 800s (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IV 1, leaf 2v), with a sixth-century Gospel leaf possessing many similar paleographic features (Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture, inv BChPh 1). These pairings draw attention to multiple aspects of these manuscripts, inviting viewers to hone in on materials, iconography, or style, and they provide a rare chance to encounter seldom exhibited items. The Getty Center’s contribution in this way raises astute questions about the diffusion of Byzantine culture more broadly as well as the specific meanings these patterns of influence might have.

The first volume of the catalogue encompasses a number of essays offering important insights into the contexts that frame an understanding of the work. Polymnia Athanassiadi, Marie-France Auzépy, Sharon Gerstel, and Robert Nelson authored particularly notable contributions. Greater integration of the catalogue essays with the exhibition’s contents, though, would help museumgoers better come to terms with what they had just seen. For instance, Anthony Cutler’s thought-provoking essay, “Byzantium and the Art of Antiquity,” omits apposite examples in Heaven and Earth that could have well served to illustrate his argument about the complex interrelationship of past and present. In contrast, Annemarie Weyl Carr integrates into her contribution several apt examples from the show—an illuminated lectionary thus illustrates the way such a Middle or Late Byzantine manuscript often “evokes enamel and precious metal” (180).

In addition to the main catalogue, a companion volume of essays, Heaven and Earth: Cities and Countryside in Byzantine Greece (Albani Evgenia and Chalkia Evgenia, eds., Athens: Benaki Museum and Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, 2013), offers regional overviews, many by the Ephorate Directors of Byzantine Antiquities. This systematic geographic coverage includes color images of Byzantine pieces that now can be more fully incorporated into scholarly discourse, such as the fresco fragment of the twelfth-century Virgin and Child from the church on Agesandrou Street in Rhodes or the pilgrimage ampullae excavated at Nea Anchialos. Its central value is in the coverage of every corner of Greece’s Byzantine remains, but current scholarship is not always integrated into the discussion of the most heavily studied areas, such as Mount Athos.

The Getty also created an accompanying mobile app, which has a nicely intuitive “salon” array of images leading to short, entertaining podcasts. The voice actor’s performance feels a little overblown, a little too “Hollywood” in a way that creates a mildly amusing juxtaposition with the no-nonsense scholarly commentary. Odd little missteps also slipped into the podcasts, such as the attribution of the pair of bracelets to “Cyprus, Greece.” The app also links to maps and silent videos of key sites, such as a lovely sequence of images of Kastoria.

Given that so much recent scholarship delves into how Byzantine art was experienced by viewers, the exhibition offers an especially well-timed chance to apprehend firsthand these works. Both the show and the two-volume catalogue are intelligently conceived and marshal a coherent and engaging view of art culled from thirty-four different collections in Greece. There are some truly remarkable pieces in Heaven and Earth. Works such as the luminous Archangel Michael icon and the deeply moving double-sided Man of Sorrows will give viewers a sense of the wonder that the medieval visitors, quoted above and in the exhibition title, felt when seeing Byzantine art in its full brilliance.

Anne McClanan

Professor, School of Art and Design, Portland State University (Oregon)