- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

In the spring of 2014, the Philadelphia Museum of Art hosted Treasures from Korea: Arts and Culture of the Joseon Dynasty, 1392–1910. There was great anticipation for this major exhibition of Korean art as it followed two others the previous year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Silla: Korea’s Golden Kingdom, 2013–14) and at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (In Grand Style: Celebrations in Korean Art During the Joseon Dynasty, 2013–14). Treasures from Korea will travel from Philadelphia, first to Los Angeles, and then Houston, yet problems of transportation and sensibility to light mean that there will be considerable replacement of objects on display in the three museums. The Philadelphia venue is the largest as is evident at the beginning of the exhibition with the forty-foot-high Buddhist banner painting, featured at the top of the grand staircase in the main hall. This national treasure of Korea has not been previously shown outside Korea and will appear only in Philadelphia. The other, approximately one hundred and fifty works at the Philadelphia Museum of Art are drawn from the National Museum of Korea and other Korean museums and from local collections in Philadelphia.

Treasures from Korea is to be praised for its organization by theme rather than chronology or media. There are five interlinking themes: The King and His Court, Joseon Society, Ancestral Rituals and Confucian Values, Continuity and Change in Joseon Buddhism, and Joseon in Modern Times. The Joseon (or Chosŏn) dynasty was the last dynasty of Korean history after the Goryeo (or Koryŏ) dynasty (918–1392). Founded in 1392, the Joseon dynasty lasted under the rule of the Yi royal family with Neo-Confucian bureaucracy until 1897, when it was elevated to the Great Korean Empire (1897–1910). The exhibition, while focusing on royal court art, also presents a broader spectrum of Joseon art and culture, showing, for example, religious practices both in and out of the court. It covers Confucianism and Buddhism particularly well. Most of the items are from the eighteenth century and onward, except for some ceramics and sculptures that predate the Japanese Invasions (1592–98) and the Manchurian Invasions (1627 and 1636). No one exhibition can include all the masterpieces of Joseon art, especially a show meant to travel overseas; but that said, a more balanced survey of Joseon art was surely possible, if only by including earlier paintings. Moreover, with many state-sponsored treasures, this exhibition has a top-down view of Korean culture that focuses on aristocratic art to the point that it neglects the autonomous commoner culture.

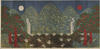

In fact, many of the objects in the first two sections of the exhibition are either from or relate to the era of King Yeongjo (r. 1724–76) and King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800), two kings who brought about the eighteenth-century intellectual and cultural Renaissance that is comparable to the time of King Sejong (r. 1418–50), known for his creation in 1446 of hangeul, the Korean phonetic alphabet. Examples of Royal Protocols (Uigwe), which recorded royal rituals and ceremonies of the Joseon dynasty, are displayed in the first gallery in handscroll or in book format. Along with screen paintings from the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, they show the precise regulations and artistic sophistication with which the Joseon court prepared and recorded its grand ceremonial program. The orderly execution of such ceremonies by the king, royal families, bureaucrats, and attendants in the court was a crucial and conspicuous reflection of the state ideology of Confucianism. The presence of a Joseon king is symbolized by a stylized screen of Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks (nineteenth century), which would have stood behind the king’s throne to show that he had the mandate of heaven. The royal Placenta Jars and other lavish and colorful screens such as Ten Longevity Symbols (eighteenth century) and Peonies (nineteenth century) convey the hope for the prosperity and welfare of the royal family, the center of the nation. Such royal, symbolic, landscape-creature screens also present the Daoist understanding of life and nature, a cosmology deeply embedded in Confucianism.

What is most intriguing about this section is how it creates organic relationships among the paintings, ceramics, costumes, and sculptures on display. For example, the Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks screen appears in one of the pages of the Royal Protocol for the Kings’ Portraits (1902) and in another screen, Royal Banquet in the Year of Musin (1848). In all three cases, Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks serves as an indicator of the un-visualizable king on his throne. The exhibition demonstrates how the screen was prepared, created, and used. The ceremonial and official garments exhibited are also comparable to the outfits of the numerous figures documented in the paintings.

In addition to paintings and documents, this first section features ceramics that show the development of Joseon ceramics ranging from early Buncheong ware (Buncheong was a short-lived technique that created wares that stood between lavish Goryeo celadon and pure white Joseon porcelain) to late Joseon ceramics represented by decorated porcelains and a natural Moon Jar (eighteenth century).

The exhibition’s second section attempts to present the impact of Confucian ideology and aesthetics on the different strata of Joseon society. Confucian influence was not only pervasive but also practical, as is shown by the Detail Map of Korea (1861). Confucianism’s gender impact is also considered. Upper-class Joseon society made strong distinctions between men and women that were reflected in their respective spaces, replicas of which, wall-papered and floored with traditional Korean white paper, are in the exhibition. The men’s study is filled with wooden furniture and writing utensils, reflecting the cultivated and austere lifestyle of the Confucian scholar. A women’s bedroom displays wardrobes, lacquerwares inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and an embroidered screen. The elegant taste of Joseon aristocrats is clear in smaller items, such as exquisitely crafted writing utensils and jeweled accessories.

The realism of Joseon art is shown by a number of eighteenth-century portraits of literary and military officials; these works describe the characteristic features of differently aged gentlemen. A genre screen shows the significant events in a gentleman’s life and provides an overview of an official’s household and its architectural surroundings. The artistic taste of Confucian scholars appears via calligraphic brushstrokes in works with the traditional Confucian motif of the Four Gentleman Plants (plum blossom, orchid, chrysanthemum, and bamboo).

Moreover, along with a printed book on Neo-Confucian doctrine written in Chinese with hangeul annotations are royal letters to women and a novel about court ladies composed in various styles of hangeul calligraphy. They present the wider range of people who benefited from and participated in the culture of late Joseon society. Likewise, Tiger under a Pine Tree (eighteenth century) by the gifted painter Kim Hong-do and inscribed by Kim’s literati mentor, Gang Se-hwang, represents the trend toward cultural gatherings and artistic collaboration in the Late Joseon. The exhibition then moves from the enjoyment of literati culture to the humor and vitality of folk paintings, as shown in Tiger and Magpies (nineteenth century) from a private collection in Philadelphia.

The third section continues the theme of Neo-Confucianism’s effect on Korean culture. It shows how Confucian rituals of filial piety were a religious way to bridge the past and future in that honoring ancestors in the other realm provided prosperity in this world. This section also illustrates how this process could become state ideology in that it achieved its goals by maintaining social order and peace. Among the various ritual vessels at the Royal Ancestral Shrine, in which Confucian memorial services are held for deceased kings and queens of the Joseon dynasty, are several pairs in brass, as well as in simply incised Buncheong ware, and in spontaneously brush-painted porcelain realistically molded into the shapes of oxen or elephants, all of which offer a chance to see the artistic results of using different materials and techniques. Also, displayed next to sets of ritual furniture and ancestral tablets is a Painted Spirit House, a hanging-scroll painting of a family’s ancestral shrine structure from the nineteenth century. Such replacements for real structures indicate how thoroughly ancestral worship was observed by every family in Joseon society with any sort of genealogy.

The next section turns away from Confucianism to show Joseon Buddhist relics, sculptures, and paintings. Despite the suppression of Buddhism during the Joseon dynasty, both court and commoners continued to practice it privately, as shown in a gilt-stone sculpture, Seated Kṣitigarbha (1515). Indeed, Buddhism revived widely in Korea after the Japanese and Manchurian Invasions, as is obvious from the great banner painting in the main hall, Śākyamuni Assembly (1653), which was painted in captivating colors on hemp for outdoor rituals. Joseon Buddhist arts inherited the iconographic features and basic techniques of exquisite Goryeo Buddhist arts, but then went on to develop its own style, especially in painting. Joseon Buddhist painting stressed the frontality of the figures, the complexity and density of the composition, and the immediacy and proximity of content. In contrast to Confucianism, Buddhism puts more weight on other realms, visualizing the spiritual in earthly forms and so extending the present to the afterlife. Moreover, late Joseon Buddhist art was highly syncretic, a point obvious in Mountain God (nineteenth century), a painting that combines Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, and age-old Korean shamanism. Hinted at throughout the exhibition is the deeply rooted Daoist ideology and shamanist spirituality that lies behind the face of Buddhist or Confucian works in Joseon culture.

The last part of the exhibition deals with works that represent the turbulent history of the final period of the Joseon dynasty and its encounter with and selective acceptance of Western culture. For example, the court-style screen painting Scholar’s Accoutrements (nineteenth century) shows bound books and scrolls along with precious antiques, plants, and inventions, all arranged in bookshelves drawn in a trompe l’oeil technique. On the wall opposite this screen are hanging scrolls by a nineteenth-century literati painter and a last court painter, both of whom employed new perspectives in their ink landscape paintings. However, the spatial limitations of the gallery meant that viewers may have had difficulty understanding the point in the narrow space between the walls for the screen and the hanging scrolls. The premise of this section is that Korean Westernization and modernization had already begun with the establishment of the Great Korean Empire, an attempt to counter the influence of Qing China by rejuvenating the glory of the Joseon kingdom. The exhibition presents significant visual evidence of how the Joseon court initiated the modernization process in Korea before Japanese colonization began. The impact of photography imported from the West is also obvious in royal portraits of the early twentieth century, which present both traditional and modern elements. Furthermore, the section makes it clear that there was reciprocal curiosity, taste, and exchange between the West and Joseon Korea, and it ends by displaying the first English novel translated into hangeul, The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan, which was published in Philadelphia in 1895. This Korean version of the novel was illustrated by the Joseon folk painter, Kim Jun-geun, who transformed the characters and scenes into Korean ones. Kim also exported to the West his illustrations of Korean folkloric culture—an example from a collection in Philadelphia is his series of Korean Games (1886).

On the wall of the corridor leading into the exhibition is a video that imaginatively animates hand-colored illustrations of people on the street cheering a royal public procession from a Royal Protocol. In the first section, the viewers can observe digitalized images of the Royal Protocols either in detail or as a whole. Moreover, the hands-on monitors for Royal Protocols and the screen of Ten Longevity Symbols link these works to others on display, allowing similar motifs and designs to be identified. The exhibition concludes with interactive computer booths where patrons can trace and print out their name transliterated into hangeul and written in characters. These interactive tools serve museumgoers well in connecting with the treasures from Korea on display.

Jungsil Jenny Lee

independent scholar