- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The March 1968 cover of Life magazine featured a large black-and-white photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe above a headline declaring her a “pioneer painter.” O’Keeffe is pictured in profile, her face lined and back curved as she leans forward with arms crossed, dressed simply in black. She sits in front of an adobe chimney, and behind her a wide, open sky and stark desert landscape stretch uninterrupted. The Life magazine cover helped cement O’Keeffe’s public image as an iconic American painter of the Southwest, a popular understanding of the artist that has persisted into the present day.

Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George, recently on view at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, aims to complicate this image of O’Keeffe through a focus on her connection to an entirely different sort of environment—Lake George, a large glacial lake in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. From 1918 through the mid-1930s, O’Keeffe lived part-time on the shores of Lake George with her partner, famed photographer Alfred Stieglitz, on the Stieglitz family’s thirty-six-acre estate. During this fruitful period of her career O’Keeffe produced over two hundred artworks, fifty-three of which are on display in Modern Nature. Cow skulls and desert mesas are conspicuously absent from this body of work, and instead the viewer is introduced to less familiar imagery: a bovine head tilted on its side, tongue curled to brush the top edge of the canvas (Cow Licking, 1921); verdant green oak and maple leaves (Leaves, 1925); and sturdy barns blanketed with snow (Barn with Snow, 1934). O’Keeffe also completed many of her most famous enlarged flower paintings while living at Lake George, including Petunias (1925) and Jack-in-the Pulpit No. II (1930), which are on display in Modern Nature.

The exhibition was organized by Erin Coe, the chief curator of the Hyde Collection, in collaboration with Barbara Buhler Lynes, the former curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in New Mexico. Surprisingly, Modern Nature is the first major exhibition to center on O’Keeffe’s relationship with Lake George. In her contribution to the exhibition’s lavishly illustrated hardcover catalogue, Coe explains that later in life O’Keeffe purposefully sought to downplay her ties to Lake George in order to distance herself from the influence of Stieglitz and from eroticized readings of her work (19). It is now commonplace to portray O’Keeffe’s time on the Stieglitz estate negatively as a stifling experience, an obstacle to be overcome on the way to O’Keeffe’s full development as an independent woman painter in New Mexico. Modern Nature works to correct this misconception, drawing together artworks from over thirty collections in order to establish the significance of Lake George.

Before setting eyes on an O’Keeffe painting, visitors to Modern Nature must first pass through a gallery with images of Lake George. Twentieth-century photographs and nineteenth-century engravings by members of the Hudson River School elucidate Lake George’s long history as a tourist destination and inspiration for artists. While Modern Nature’s installation at the Hyde Collection was a mere six miles from Lake George, the Adirondacks are unfamiliar territory to many Californians, and so this gallery provides valuable context that informs the rest of the exhibition. Also installed in the gallery are a porcelain plate and illustrated book plucked from the de Young’s permanent collection, two of about half-a-dozen artworks from the de Young scattered throughout Modern Nature. At the center of the gallery is a column printed with an imposing portrait of O’Keeffe at Lake George, taken by Stieglitz in 1921 and blown up to a large scale. It is the first of a number of Stieglitz photographs that populate the exhibition, showing O’Keeffe holding a branch of apples, kneeling by a flowerbed to draw, and repairing the roof of her painting “shack” with a friend. These lovely photographs reveal a lesser-known side of the artist, providing a counterpoint to her desert portraits. Significantly, the didactic text alongside the photographs shies away from the topic of the artists’ relationship (a theme that so often dominates discussions of O’Keeffe’s early career), instead keeping the focus on the photographs’ ability to describe O’Keeffe’s experiences at Lake George.

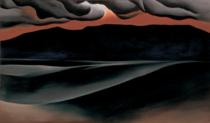

The second gallery is hung with O’Keeffe paintings grouped around the theme of Abstraction. Series I No. 10 and No. 10A (1919) are placed at the entrance to the gallery, small but arrestingly luminous paintings with abstract anthropomorphic forms of pale green, yellow, and white that glow brightly on dark backgrounds. The canvases are a timely reminder that despite the frequent reproduction of O’Keeffe’s work, her work’s masterful use of color and light can only be fully experienced in person. Series I No. 10 and 10A may, the wall text explains, “allude to the artist’s bare knees and thighs” as she rows across Lake George, although Coe suggests a more ominous inspiration—the paintings could also refer to an incident in 1919, when Stieglitz and O’Keeffe came upon two boys with a capsized canoe and were only able to rescue one of the boys while the other drowned (36). Series I No. 10 and 10A remained in O’Keeffe’s collection until her death, and have not been widely exhibited. They are exemplary of Modern Nature’s ability to bring forth lesser-known O’Keeffe paintings, creating delightful surprises for an artist with a well-traveled oeuvre.

The remainder of Modern Nature is organized into the themes of Landscapes, Still Lifes, and Flowers, which share a large room at the back of the exhibition, and Trees, Leaves, and Barns, which occupy the final two small galleries before the visitor exits to the gift shop. The galleries offer surprises—the landscape Lake George, Autumn (1922) has not been on display since the 1920s—as well as old favorites, like Petunias (1924). Unfortunately, many of O’Keeffe’s canvases are small, and despite standout moments, the exhibition feels rather abbreviated, especially in the wake of the sprawling David Hockney exhibition that previously occupied the space (click here for review). Further, the organization of the paintings by subject matter can work to decrease tension; for instance, the similar-looking still-life paintings begin to meld together, and are easy to pass over quickly. Happily, other combinations of paintings invite close examination, as they render visible the importance of O’Keeffe’s experimentation at Lake George to the development of her techniques of abstraction. One particularly potent example is a series of five paintings of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit flower, all completed in 1930. The first painting the visitor encounters is Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI, a simple curved line of white, with a halo radiating into dense layers of black and burgundy. Moving one’s gaze to the canvases at the left, these elements become increasingly representational, so that the final painting, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. II, depicts a discernible flower nestled between green leaves. The sequence allows the viewer to watch O’Keeffe’s process unfold, as different aspects of the same flower move between abstraction and figuration, becoming dimensional and flattened, with lines blurred and sharpened, colors proliferating and simplified, and forms dramatically reconfigured.

Overall, Modern Nature is effective in asserting the formative influence of Lake George on O’Keeffe’s work, filling out an understudied chapter of the artist’s career and providing insights into the development of her iconic style. However, the exclusive focus on works made at Lake George hinders the curators’ ambitions to establish the significance of the period to O’Keeffe’s work as whole. Without the inclusion of a selection of O’Keeffe’s later paintings, the exhibition is overly reliant on the presumption that viewers will be knowledgeable enough to infer the connections between the paintings of Modern Nature and O’Keeffe’s images of the Southwest. The inclusion of some of O’Keeffe’s later works would have benefited Modern Nature, both to fill out the exhibition and to powerfully illustrate the resonance between the two periods: imagine the organic curves and depths of Leaf Motif, No. 2 (1924) in conversation with Pelvis with Distance (1943) or the swirls of Grey Tree, Lake George (1925) next to Cottonwoods (1952). Modern Nature does make an exception for one O’Keeffe painting—Flag Pole and White House, painted in 1959 while the artist lived in New Mexico—which hangs next to its predecessor, Flagpole, from 1925. In this pairing, O’Keeffe returns over thirty years later to create a second version of an image of the shed that served as Stieglitz’s darkroom at Lake George. The delight in comparing these two works, each fascinating in its own right and all the more so in relation to one another, drives home Modern Nature’s insistence that a consideration of O’Keeffe’s connection with Lake George is crucial to a profound understanding of her work across the decades.

Emma Silverman

PhD candidate, History of Art Department, University of California, Berkeley