- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

It is appropriate that State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970, the wonderful, timely, necessary exhibition curated by Constance Lewallen and Karen Moss, was at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, which in the context of the New York art world is as far away psychologically from the gallery districts of Chelsea and the Lower East Side and the museums of Midtown and the Upper East Side as Los Angeles and San Francisco and other hotbeds of California art are geographically. The parochialism of New York—Manhattan, really—is well known, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s, just as it is now, a few square miles of Manhattan sat at the center of the art world. The major galleries held court, collectors were plentiful, and critics had outlets in which to publish. Artists lived in close proximity to one another, fostering an intense competition not only among themselves but also with the recent past. For New York-based Minimalists and Conceptualists (both successful and aspiring), what transpired in California was difficult to fathom. Many tended to complain that artists in Los Angeles, for instance, did not suffer enough, a gripe John Baldessari heard frequently on his many trips to New York. And for those inhabiting downtown lofts that lacked the most basic amenities, where the monuments of industrialism, soon to become ruins, loomed large in Manhattan and the outer boroughs, it was difficult to understand how in Los Angeles radical art could be produced in the steady glow of sunshine, in a city with a gluttonous amount of space, spreading out unfettered until redirected either by mountains, desert, or ocean.

At the core of State of Mind, as well as with the majority of projects associated with Pacific Standard Time (as part of which the exhibition appeared in 2012 at the Orange County Museum of Art) (click here for review), is an examination of place. California, but primarily Los Angeles, to a lesser degree San Francisco, and to an even lesser degree areas such as San Diego, is the main protagonist: how a specific geographic locale—made mythical by both its exalted and contested spot in the public’s imagination—shaped the production of heterogeneous and in some cases truly unique works of art. It is hard to imagine the equivalent of State of Mind for New York City. There has never been a similar expectation, especially in the late 1960s and early 1970s, that New York itself was the source for innovative art. Such things as critical discourse, the specter of art history, and the market—each arising in New York but expressed in critical writings and commonly held belief systems as independent from the day-to-day realities of life in this densely populated metropolis—instigated progressive art. Critics did not need to defend New York in the face of skeptical viewers, nor find the meanings of complex artworks in clichéd understandings of the city. They did not have to write observations like this when giving a roundup of the art scene: “All levels of reality and fantasy [in Los Angeles] merge into the single concept of a push-button environment, a pill for every mood, with the automobile as the ultimate time machine” (Helene Winer, “The Los Angeles Look Today,” Studio International 183, no. 937 [October 1971]: 127). In terms of art-world geography, New York was, and still is, the white cube.

New York’s locational neutrality in the discourse of contemporary art lurks in the background of State of Mind. But the show does not strike a defensive posture, as was somewhat apparent in Paul Schimmel’s thought-provoking and impressive Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974–1981 (also part of Pacific Standard Time), which took pluralism as a virtue, and saw the diverse art assembled in the cavernous Geffen Contemporary as an antecedent—unacknowledged in large part by art history—to the postmodernist discourse that took hold in New York in the early 1980s. State of Mind is rather matter of fact, which is good because much of the art presented is arguably the best made anywhere from that time, a sentiment shared by Thomas Crow with regard to the work exhibited at Pomona College in the early 1970s, much of it by artists (Bas Jan Ader, Baldessari, Ger van Elk, William Leavitt, Allen Ruppersberg, and William Wegman) on view here (Thomas Crow, “Disappearing Act: Art In and Out of Pomona,” in It Happened at Pomona: Art at the Edge of Los Angeles, 1969–1973, eds., Rebecca McGrew and Glenn Phillips, Claremont, CA: Pomona College Museum of Art, 2011: 38).

State of Mind sidesteps many of the clichés that have shaped the understanding of this art—Los Angeles and the influence of Hollywood, San Francisco, and the impact of hippie culture—and resists arranging works by geographic location alone. Lewallen and Moss created thematic constellations such as mapping the land, private/public space, and the body as means to organize work varied in form and content. These are categorizations made from retrospectively recognized affinities, as what defined the California art scene circa 1970 was a rugged individualism—a general attitude, as Joan Didion often describes, so central to the collective identity of the region. Like minds tended to congregate, and artists did not have to confront things they did not support. Sheer distances between one place and another, whether in Los Angeles, or between Los Angeles and San Francisco, were a factor in the rise of these self-sustained practices, but the art world as a whole at this time was becoming increasingly global such that it was far more likely for an artist in Los Angeles to show in Amsterdam or London than in San Francisco. In many ways, State of Mind is a collection of singular voices presented plurally, a symphonic composition in which every instrument is heard distinctly.

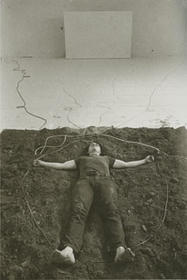

The show begins in a small, transitory space with an assessment of the land. Baldessari’s California Map Project (1970) and Robert Kinmont’s 8 Natural Handstands (1969) are two somewhat absurd interventions that despite their engagement with California’s natural wonders are anything but a kind of Earth art. The bulk of the show resides in two large exhibition spaces. One is dominated by an installation of light boxes, projected photographs, and some furniture that document Ruppersberg’s seminal Al’s Grand Hotel (1971)—a project that had him transform a single-family home in Hollywood into both a total artistic environment and a functioning hotel. A recently discovered recording of Terry Allen’s live performance at Al’s Grand Hotel suffuses the space with bawdy country and Western tunes. The rough-hewn energy of the songs complements much of the work in State of Mind, pieces that often lack an obsessive formalism (like the inimitable videos of Wegman or Ilene Segalove) or possess an uncontainable, palpable intensity—whether the body prints of David Hammons or the performances of Barbara Smith or Linda Montano or even Chris Burden. There are surprises in the show such as Paul McCarthy’s slide projection documenting the events of a single street corner and a luminous, wall-mounted Finish Fetish piece by Michael Asher from 1966. Some things are utterly strange, including the work of Paul Cotton and his pink penis costume, the “people’s prick” as he was sometimes called. There are the expected works of Ader, Baldessari, Bruce Nauman, and Ed Ruscha, but three relatively unknown artists from San Francisco—Terry Fox, Howard Fried, and Bonnie Sherk—deserve greater scholarly attention. Works that are decidedly political, such as those by ASCO, Martha Rosler, and Allan Sekula, refrain from didacticism, and in the case of Sekula and his Untitled Slide Sequence from 1972, put forward hauntingly moving pictures of workers leaving a factory—a kind of Lumière brothers for postwar Southern California.

One of the paradoxical revelations of State of Mind, an exhibition dedicated to examining the West Coast iteration of Conceptual art, is how it makes clear the inadequacy of this moniker. In her catalogue essay, Lewallen gives a brief overview of the generally received tenants of Conceptualism: an engagement with the question of art as such, an interest in systems, linguistic theory, etc. She rightly explains that much of the work identified as Conceptual in California is different in spirit from more normative definitions of this art. Over the years, as much out of convenience as anything else, work that moved away from medium-specific concerns in the 1970s, and that took philosophical problems or political critique as a starting point, has been labeled Conceptual. The art-historical story of Conceptualism has been largely shaped in essays from the late 1980s and early 1990s by Benjamin Buchloh and Charles Harrison, and although divergent in opinion, and representing two ideological poles, both Buchloh and Harrison have a specific understanding of this kind of art, with the movement culminating by 1972, if not earlier, and located primarily in New York. Conceptual art, as conceived by the two critics, and as practiced by such figures as Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, and Lawrence Weiner, had two options: to be either a managerial, administrative activity that reflects the changing conditions of late capitalist society or to be ontological investigations into the nature of art. These analyses have proffered powerful readings and have loomed large over subsequent interpretations of a broad range of art generally classified as Conceptual. But in State of Mind, pieces that are closest to that described by Buchloh and Harrison—the language works of Guy de Cointet, the films of Morgan Fisher, the image-text combinations of Leavitt—are far too poetic, humorous, and downright strange to fit neatly into what have become the overarching categories of Conceptualism.

In fact, if a general trait runs throughout this show, it is that the works are deeply human. They are about life, the world, and all the existential messiness that follows. They do not ask an ontological question about art, but rather a pragmatic one: how to make a work of art when anything can be art? It is a question that is still unresolved, and shapes the production of much contemporary art today. How fitting that some of the most profound answers to this query occurred in California in the early 1970s, a place synonymous with the reinvention of the self, where anything seems possible, of land and communities begot by dreams of being something entirely different.

Alexander Dumbadze

Associate Professor, Department of Art and Art History, George Washington University