- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Considering Paul Gauguin’s notable impact on the development of modern art, it seems remarkable that Gauguin: Metamorphoses is his first monographic exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and only the second major presentation of his art in New York since 1959. Perhaps even more surprising, this show, organized by Starr Figura, the Phyllis Ann and Walter Borten Associate Curator, with Lotte Johnson, curatorial assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints, foregoes the expected focus on Gauguin’s paintings. Instead, the paintings play a supporting role, along with wood carvings and ceramics, in an exploration of the theme of transformation in his prints and transfer drawings. Although the subject matter is familiar, mostly images of Breton and Tahitian women, the show offers new insights into Gauguin’s method of combining diverse sources and usually distinct artistic techniques.

Framed as a process-oriented show, its treatment of Gauguin and his working methods is nonjudgmental. This approach is similar to that previously adopted by the curators of Gauguin: Maker of Myth (Tate Modern) in 2011 as a corrective to postmodern critiques of the artist’s questionable behavior, specifically his treatment of women, and his problematic “primitivist modernist” aesthetic. While the 2011 Tate exhibition sought to restore the significant role narrative played in Gauguin’s oeuvre, Gauguin: Metamorphoses concentrates on his technique. The curators organized the installation around the artist’s three major printmaking projects—the Volpini Suite (1889), the Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent) Suite (1893–94), and the Vollard Suite (1898–99)—interspersed with watercolor monotypes and followed by a gallery of oil-transfer drawings, a process he invented for transferring images during the last years of his life in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands (ca. 1899–1903). The chronological arrangement of the artworks emphasizes the development of Gauguin’s printmaking as he moved from conventional to innovative methods, some of which are still not understood. The exhibition also tracks his travels to Pont-Aven, Arles, Martinique, Tahiti, and the Marquesas Islands, all locations that served as inspiration for his mythic visions of a preindustrial paradise at home and abroad.

The curators take advantage of the reproductive nature of printmaking to emphasize Gauguin’s ideas of transformation: prints appear in multiple states and contexts, both in suites and separately in thematic groupings. They showcase impressions of woodcuts alongside woodblocks, drawing attention to the particularities of Gauguin’s printing process, which began with a barely there, test print on pink paper. The exhibition further underscored his inventive approach by juxtaposing his impressions of the Noa Noa Suite with those printed by Louis Roy, a painter friend and a professional printer the artist hired to publish an edition of about thirty. Roy’s standardized, consistent, and sharper contoured woodcuts contrast with Gauguin’s more experimental, atmospheric ones, which purposely lack regularity and accurate registration of color.

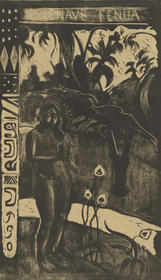

A wide variety of objects set the context for the prints and transfer drawings. Along with renowned paintings from his Tahitian period, such as Te nave nave fenua (The Delightful Land) (1892) and Two Tahitian Women (1899), notable works include ceramics that initially adhere to East Asian and Art Nouveau styles and, after Tahiti, develop into rough, often violent, forms, exemplified by the goddess Oviri (Savage) (1894), as well as carvings on found wooden bowls, branches, and tree trunks, especially the cylindrical, totem-like figures he named ti’ii—though they hardly resemble the actual Tahitian statues, as Elizabeth Childs comments in her catalogue essay on Gauguin’s sculpture (42). In addition, the exhibition offers a cross-section of his written work. Three major texts, all accompanied by illustrations, are on display: Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent), published posthumously in 1924; Le Sourire: Journal sérieux (The Smile: Serious Newspaper), his satirical newspaper begun in 1899 that critiqued the colonial administration of Tahiti; and his treatise Esprit moderne et le Catholicisme (Catholicism and the Modern Mind), from 1902.

The contents and arrangement of the exhibition reinforce its overarching thesis concerning the primacy of transformation in Gauguin’s work. Three related artistic methods for realizing change are postulated though not explicitly stated: compositing, shifting mediums, and reversals. Gauguin frequently created new images through a composite process. For example, he re-envisioned both Eastern and Western religious icons, combining recognizable narratives or figures to fabricate his own deities, as in Idol with a Pearl (1892), one of his ti’ii, which depicts a Maori woman in the pose of an enlightenment Buddha in a niche. This sculpture weds Tahitian, Buddhist, and European motifs in an unprecedented manner and unites ritual and aesthetic functions and diverse materials—tamanu wood from Tahiti and a miniature pearl and gold chain, probably from Europe.

In other works, instead of compositing subjects and materials, Gauguin reimagined mythological scenes in a “primitive” style, juxtaposing dissonant artistic techniques. A productive incongruity, for example, arises between two distinct relief-print methods in his woodcut L’Enlèvement d’Europe (The Rape of Europa), from the Vollard Suite. The central scene portraying two female figures, one riding a bull, has the character of a roughly defined woodcut with black highlights on a white ground whereas the more detailed peahen in the upper-right corner recalls the approach of a Renaissance metal cut or wood engraving with white incised lines forming a pattern on the bird’s black body and surroundings. The resulting image, therefore, consists of two sections with contrasting treatments of form and tone. This work also inverts the usual mirrored relationship between matrix and finished print: a comparison of the woodcut with the woodblock on display nearby shows that they share the same orientation, an effect accomplished by mounting this print on thin, transparent paper with the ink side down.

Another means of metamorphosis is the reworking of a subject in different mediums, evident in the thematic groupings, in which subject matter spills over material boundaries. Perhaps the most complete example of this phenomenon appears in the first gallery: Gauguin’s representation of a Tahitian Eve encountering a winged lizard (an animal native to Tahiti unlike snakes), undergoes a series of alterations in color, texture, orientation, composition, and meaning. The grouping starts with his well-known painting, Te nave nave fenua (The Delightful Land), and a study for it with pinholes for transferring the female nude to canvas, and then shifts to a carved and painted oak panel of Eve and a serpent, which preceded the painting. It concludes with a woodblock, five impressions in various states, and a watercolor monotype, all prompted by the painting and sculpture. The artworks in this section trace Gauguin’s exploration of this subject in two- and three-dimensional media, both before and during his Tahitian period.

The aforementioned, elaborate thematic ensemble calls attention to Gauguin’s use of reversals as one more productive method of reinvention: the woodcut process literally inverts the image, and through inking and wiping, which involves an element of chance, the scene alters in tone and resolution, dramatically darkening and losing clarity. Gauguin also exploited the artistic device of translation and reversal in his transfer drawings, which, as paper conservator Erika Mosier explains in the catalogue, result in unpredictable effects, irregular lines, and blotchy surfaces, caused by drawing on a clean sheet layered over an inked one (65–70). Inverting the language of drawing, the side with the printed composition is referred to as the recto whereas the side on which the artist drew is the verso.

As argued on the wall labels and in the catalogue, the woodcuts offered Gauguin an unmatched artistic opportunity for effecting his desired transformations and for conveying a psychological darkness, less apparent in his other works. Figura’s catalogue essay adopts Alastair Wright’s argument that the woodcuts through their blackness, lack of focus, and unresolved character embody Gauguin’s melancholy attitude toward Tahiti as an unattainable and untenable paradise (Alastair Wright, “Paradise Lost: Gauguin and the Melancholy Logic of Reproduction,” in Wright and Calvin Brown, Gauguin’s Paradise Remembered: The Noa Noa Prints, Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 2010). However, this interpretation understates the sensuality and violence of the forms and the cutting and gouging of the printmaking process itself. Consider the comparison of the painting Te nave nave fenua (The Delightful Land) and the woodcuts it inspired: it illuminates the transformation from a “technicolor” paradise, where Eve dominates, to a dark, fiery, paradise lost (hell), where Eve appears subjugated to her surroundings. Although Eve’s rounded form and her encounter with the lizard and the flower are maintained, the setting becomes more threatening, populated by prickly foliage and a tornado of incised lines. Here, as elsewhere, the visual evidence does not support Wright’s hypothesis about Gauguin’s evocation of a disappearing culture—an argument predicated on a present-day association of blurring and indistinctness with loss and forgetting. More plausibly, another reversal of expectations is at work: rather than replicating the more traditional paradise in his painting, Gauguin appears to have invented his own “delightful land,” where, in Symbolist terms, the dark and macabre subvert convention and allow for unabashed freedom of expression.

Gauguin: Metamorphoses downplays the darker, more disturbing side of Gauguin’s persona, though Hal Foster in his catalogue essay mentions the “seductive and traumatic” character of the “primitivist’s dilemma” (the unresolved desire to embrace difference yet retain sovereignty over the other) (57). Despite presenting a whitewashed version of the artist, it offers a rare opportunity to see him as more than an avant-garde painter. Paintings are on display, but they serve as the starting point for more innovative explorations in other mediums. In comparison to the works on paper, wood carvings, and ceramics, they seem more conservative in style and technique. By prioritizing Gauguin’s innovative use of materials and his invention of the oil-transfer drawing method, the curators perform their own metamorphosis of his legacy. They position him as both a father of modern printmaking and a progenitor of the twenty-first-century multimedia, appropriation artist who privileges handcrafting and hybridization.

Isabel L. Taube

Lecturer, Department of Art History, Rutgers University