- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece is an exhibition of about one hundred objects of Greco-Roman art drawn entirely from the collection of the British Museum. The show was in many ways welcome. Public displays of ancient art are in short supply on the West Coast north of Los Angeles, and the British Museum, of course, has one of the world’s great collections of this material. While most of the items included in The Body Beautiful are more often in the British Museum’s storerooms than their display vitrines, the exhibition was not without its stars, such as a red-figure kylix of ca. 510 attributed to Epiktetos and showing a dancing girl and a youth playing the pipes (British Museum GR 1843,1103.9 [Vase E38]). Ancient Greek art of this quality and magnitude has not recently (or perhaps ever) been seen in the Pacific Northwest.

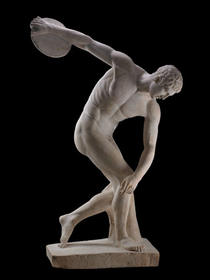

Curated by Ian Jenkins and Victoria Turner, the exhibition was intended to make a big splash. That was apparent from the striking and immense photographs of the Townley Discobolus (British Museum GR 1805,0703.43 [Sculpture 250]) that graced the facade of the Portland Art Museum for the duration of the show. It was apparent as well from the extensive program of events organized to accompany the exhibition. These ran the gamut from the expected but welcome, such as lectures by noted scholars including Andrew Stewart and Richard Neer, to the more unusual: e.g., a Nike-sponsored discussion of the exhibition at the museum by a panel of world-class athletes including Carl Lewis, Joan Benoit Samuelson, and Ashton Eaton; or a program of classical and modern dance based on the body and performed by Oregon Ballet Theatre.

The Townley Discobolus was very much the show’s centerpiece, appearing in the middle of the main suite of galleries and appearing on not only the museum’s facade, but also the catalogue’s cover. According to that catalogue’s introduction by the British Museum’s director, Neil MacGregor, the sculpture was the “star of this exhibition,” making “his first visit to the United States” (7). The prominence accorded to this figure made sense in many ways, for MacGregor is right that the Discobolus is “one of the most famous images of an athlete ever made,” and The Body Beautiful stood in a direct, if somewhat vague, relationship to the London Olympics of 2012. But most readers of this review will see that what made sense from the sporting perspective may not have worked so well from the historical; simply put, the Townley Discobolus is a Roman sculpture, and so its relationship to the exhibition’s alleged subject, the body beautiful in ancient Greece, is obscure. In contradistinction to earlier trends, modern classical scholarship usually considers works such as the Townley Discobolus, a Roman marble version of a Greek bronze original, to be products of Roman, not Greek, culture. The point is arguable, but it is not negligible. The title The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece implied a historical and historicized subject, yet the show’s inclusion of works such as the Discobolus was more fitting for a non-historicized show, perhaps of treasures of Greco-Roman art from the British Museum.

This conflict bedeviled the entire exhibition. If the show’s title is to mean anything, it must mean that Greek ideals about beautiful bodies are of interest as a historical category, that they therefore are not universal. And, indeed, much of the best scholarship on the ancient world in recent decades, by both art historians and, more generally, all kinds of scholars in the humanities, has emphasized the ways in which Greek ideals of bodies, beauty, and sexuality were constructed and peculiar, not natural and universal. At times, The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece knew this. The point came through well, for example, in the fine catalogue essay by Ian Jenkins, but Jenkins’s scholarly insights were unfortunately not made available to viewers of the exhibition, even in the diluted form of wall labels. And the point was made as well in the exhibition itself through the admirably frank display of so-called erotica, including several explicit depictions of both male-female and male-male sexual intercourse. (To the credit of the Portland Art Museum, and I think bucking the trend of modern U.S. museology, these objects were presented without warning labels and also without the voyeuristic “secret room” treatment they sometimes get. Likewise to the museum’s credit is that its active program of K–12 education was not in any way derailed by the presence of such objects.)

But at other times, The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece seemed oblivious to the notion that ideals of the body might be culturally and historically constructed and that it therefore will not do to use Roman objects to show what the Greeks thought of bodies. A concrete example illustrates the problem. The exhibition opened with a fourth-century BC tombstone, likely Attic (British Museum GR 1839,1102.1 [Sculpture 626]), depicting a standing male, nude except for a cloak draped loosely over one shoulder, holding a strigil. The piece is of high quality and was well displayed, placed upright and at about the height it would have been seen in its original cemetery context. I took several different student groups through the exhibition, and I always used this object to introduce the strangeness of the Greek attitude toward the body when compared to modern ones. I believed that my reading was relatively sophisticated historically. Yet in preparing this review I was horrified to discover (from Jenkins’s catalogue essay) that the tombstone’s Greek inscription, naming its subject as “Tryphon, son of Eutychos,” is an addition from the Roman period and, indeed, that the figure’s nicely classical head had been recut in the Augustan period (and so was a nicely classicizing head). All of this information is fascinating and crucial to understanding what this piece can tell us about the body beautiful in ancient Greece and, more generally, the Mediterranean world, but none of it was made available to viewers of the exhibition who did not read the catalogue.

Examples like this could be multiplied, since as with virtually any exhibition of Greek art that includes sculpture, Roman culture necessarily played a significant role in The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece. Yet the exhibition continually wavered between treating everything as Greek/universal or historicizing the objects. There were certainly some interesting stabs in the latter direction, such as the juxtaposition of a medal from the first modern Olympics in 1896 and its iconographic model, a Roman bronze depicting the Olympian Zeus. Likewise, in a section entitled “Outsiders,” the exhibition tried to make the case that the expansion of the Greek world during the Hellenistic period generated an interest in the other because it brought so many others into the Greek world. This last thesis is surely debatable, but it is interesting, historically specific, and could have been well argued with visual material. But that kind of interest in recognizing that Greece was not Rome and that archaic Greece was not Hellenistic Greece was the exception, rather than the rule. Although the show included large-scale models of Olympia and Athens made in the twentieth century, it did so only to let viewers know what these sites looked like and so missed a golden opportunity to talk about the modern reception of the classical, a subject that would have made apparent the complex relationship between ancient and modern ideas about beautiful bodies.

Given what I have said about the show’s lack of clarity about the historical force of its theme, it is not surprising that the show’s historicizing title belied its installation. The exhibition was shown like the typical treasure exhibition. Bright spotlights were used on most of the sculptures. The vases, unfortunately, were often in vitrines that had been pushed against the wall, so that one could see only one face of a particular vase. This made sense in some places, where only one face was being used to make an iconographic argument, such as in the section on the labors of Herakles, “an ancient Superman.” But, in other places, both sides of a vase are clearly essential to understanding how the Greeks constructed notions of the beautiful (and ugly) body.

So, from the scholarly art-historical perspective, The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece did not bring much. The same goes for the catalogue; Jenkins’s introductory essay is, as noted above, a highly competent introduction to the issues raised by this exhibition, but it will not be a revelation to scholars. The rest of the catalogue, while sumptuously illustrated (every piece in color), has only extremely short entries (one or two sentences) and no references to further bibliography. The catalogue’s text, aside from the introductory essay, reprints the exhibition’s labels (and the audio guide, annoyingly, essentially consisted of little more than a man reading these same labels with a British accent). Likewise annoying in the catalogue are the often punning (“Brainchild” for a depiction of the birth of Athena) or presentist (“See through Dress” for a fifth-century kore) titles given to each object.

William Diebold

Goodsell Professor of Art History and Humanities (emeritus), Reed College

Acknowledgments:

The author benefited greatly from discussions of this exhibition with Richard Neer and, especially, with the students in his introduction to art history class at Reed College in the fall of 2012.