- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Prior to the opening of the Musée du Louvre’s spectacular new galleries for Islamic art in September 2012, this renowned collection largely had been in storage for the last thirty-five years, with brief reinstallations in 1987 and again in 1993. After such a long and much anticipated wait, the galleries did not disappoint this reviewer; rather, they absolutely dazzled.

Five lengthy, successive visits were just enough to get a sense of the sheer depth of this remarkable assemblage, which encompasses the breadth of Islamic art, traditionally defined as extending from Spain to India between the seventh and nineteenth centuries. Drawn from the Louvre’s collection of 15,000 objects as well as some 3,400 transferred from the Musée des Arts Decoratifs, the resulting installation offers an in-depth view of nearly every aspect of Islamic art, with over 2,500 works of art on view, an impressive number given that ten percent is the more typical ratio of a museum’s collection on exhibition at any one time. Two notable exceptions are the mediums of textiles (the major holdings still at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs will be tapped for future loans) and manuscript illustration, which is better represented perhaps by the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Given that half of the new gallery space has natural light, these lacunae are perhaps somewhat fortuitous.

Designed by architects Mario Bellini and Rudy Ricciotti, the space newly created for the galleries encompasses over 30,000 square feet on two levels. The lower level was excavated beneath the Visconti Court, while the upper one, within the courtyard proper, is enclosed by glass walls and covered by an incredible glass and steel roof. The case work and interiors are as contemporary as the architecture; apart from one long floor-to-ceiling wall on the lower level (resulting in a very lengthy and somewhat awkward gallery), the exhibition space is entirely open.

As fantastical as the space may sound (but perhaps the glass and steel Pyramid, I. M. Pei’s 1989 architectural intervention, serves as preparation), it works wonderfully well for the display of the collection, while the glass walls of the upper level mediate between old and new, revealing and visually integrating the carved stone facade of the nineteenth-century Visconti courtyard. Perhaps in an attempt to create a link between the architecture and the collection it houses, the undulating roof has been variously described as a veil or even a sand dune. But, refreshingly, there is no Middle Eastern-inspired architectural or design concept at work; rather the multitudes of first-rate objects on view, including some exceptional architectural elements, help to contextualize one another while the lightly imposed but skillfully realized curatorial narrative provides the historical and cultural overlay.

The decade-long reinstallation project was led by the Louvre’s head curator of Islamic art, Sophie Makariou, with the assistance of a team of curators, researchers, and conservators. Their task was made all the more daunting by the fact that the collection was in many instances both understudied and underconserved. Among the previously unpublished or largely unknown material, perhaps the most remarkable discovery was the disassembled stone vestibule from one of the grand residences of fifteenth-century Mamluk Cairo, which had been crated and shipped to Paris in the late 1880s. Intended for exhibition at the 1889 World’s Fair, the crates instead remained in storage through the end of the twentieth century. Relying in part upon drawings made in the 1880s, the now reassembled entrance hall installed on the lower level provides a wonderful architectural foil for the many incomparable Mamluk objects displayed nearby.

Divided between the two floors, the installation is organized loosely along chronological lines. The upper level spans the years 700 to 1000 (but actually extends in some instances to about 1200) with a smaller thematic section on epigraphy. On entering the space, following a series of introductory text panels, the visitor is greeted by a pair of very large, colored drawings mounted on canvas, part of a group of nine full-scale replicas of the mosaic panels from the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. Made on site in 1929, under the auspices of the French Institute in Damascus, the drawings preserve the pre-conservation state of these justifiably famous mosaics, which here serve as a kind of didactic prelude emphasizing the Late Antique roots of much of Umayyad art. This level also includes a large amount of archaeological material, much of which was excavated at the southwest Iranian city of Susa. In particular, the ceramic wares help to delineate the early history of this important medium in Islamic art in much the same way as the pottery excavated at the eastern Iranian site of Nishapur, and now largely preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Presented together, along with other contemporaneous but unprovenanced objects, the Susa finds at the Louvre document daily life in a flourishing urban center during the Abbasid caliphate. They are juxtaposed against still more splendid objects and architectural elements from Samarra, the Abbasid’s alternate capital to Baghdad from 836–892, as well as from Fatimid Cairo, and the Spanish Abbasid caliphate in Cordoba.

The lower level covers the three periods 1000–1250, 1250–1500, and 1500–1800, which are further divided according to region (ranging from North Africa to northern India) or at times by medium. Works of art dating to the years 1000–1250, primarily ceramics and metalwork mainly from Iran as well as Syria, are displayed in a long closed gallery along one side of the otherwise open expanse of this level. Though not an initially inviting space, the intelligent and visually comprehensible analogies made by the curators help to draw the visitor in—for instance, relief decoration in metalwork in comparison with related relief work in glazed and unglazed ceramics. The vast adjacent space is arranged in a series of “pathways” loosely defined in part by the casework and by the installation of large-scale architectural elements. Grouped around the previously noted stone vestibule are related Mamluk objects such as the famed Baptistère de St. Louis, along with a brilliant array of enameled and gilded glass, carved and inlaid wood doors, and a section of an inlaid stone fountain.

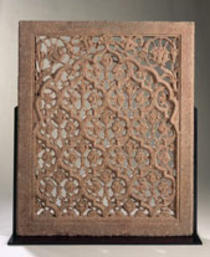

The latest chronological division highlights the period of the so-called Gun Powder Empires of the Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman dynasties. Here one is pulled between large-scale displays of Persian carpets or an entire and glorious wall of Iznik tiles (for which the label carefully notes that this is not a reconstruction from a single building), along with pierced window screens—carved stone jalis from India and wood mashrabiyya from Ottoman-era Egypt—and vitrines filled with more delicate objects such as jewel-encrusted Mughal jades and brilliantly glazed Safavid ceramics.

From a curatorial perspective, perhaps the main drawback of the new galleries is also one of its greatest beauties, the use of extensive natural light on the upper level. However attractive, the glass roofing and floor-to-ceiling windows preferred by contemporary architects and the directors and boards of trustees who hire them to create novel museum spaces are incompatible with a great deal of Islamic art such as carpets, textiles, manuscripts, and miniature paintings, all of which are highly sensitive to light. The fixed nature of the natural lighting in about half of the gallery space renders it less flexible, providing no place for textiles and works on paper or parchment among the earliest material shown on the upper level. On the lower level, a single long and cramped vitrine serves for the display of manuscript and album paintings as well as calligraphy and illumination, which are here treated thematically rather than by date or region.

Perhaps because the installation of the lower level is denser and covers a much greater time span than the one above, this section by comparison is somewhat more difficult to penetrate. A colleague of mine who attended the opening and had just a few hours to take in the installation was close to tears with both delight and frustration as she tried to figure out the most expedient way to negotiate this level. The objects, however, are so superb and so numerous that it may be best, for those with a limited schedule, including the specialist, to simply allow their eyes to lead them. Like the Louvre itself, whose best-known masterpieces are embedded within a complex of galleries, the Islamic installation does not quickly or easily reveal its chief treasures.

The Islamic galleries are in fact very much about the process of observation and discovery. While there are didactic materials, they are non-intrusive; labels are brief and text panels are kept to a minimum, in part no doubt because they are generally bilingual or trilingual. There are digital monitors scattered about, but one gets the sense that the visitor is expected to look rather than read. One particularly pertinent use of recorded didactic materials has to do with the inscribed texts that pervade so much of Islamic art. Within the installation are several auditory stations that supply recitations of the Arabic, Persian, or Ottoman Turkish inscriptions on nearby objects, serving to remind that this is an art with something to say for those who are willing to take the time to listen.

Apart from the ingenious beauty of its architecture, the most exceptional feature is the overall openness of the installation combined with the sheer magnitude of objects on display. (The Islamic art galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which reopened in 2006, also have an open plan, although the installation there is less dense with objects; other works from the Islamic collection are displayed elsewhere in the V&A in two different settings based on medium, where they can be viewed in an intercultural context with other decorative arts in related media.) Writing in 1976 about the then new Islamic art galleries at the Metropolitan Museum, which when they opened in 1975 were a watershed in terms of the quantity and quality of the display and the scholarship behind it, Oleg Grabar attempted to explain the significance of bringing together, often within a single vitrine, such large numbers of related objects. He suggested that works of Islamic art perhaps are not best understood within “a setting that excerpts them from their purpose, and that they are in fact to be seen as ethnographic documents, closely tied to life, even a reconstructed life, and more meaningful in large numbers and series than as single creations.” Grabar went on to discuss his belief in the need for an architectural context, noting that it is the “real or fantasized memories of the Alhambra, of Isfahan or of Cairene mosques [that] provide the objects with their meaning” (“An Art of the Object,” Artforum 14 [March 1976]: 36–43, 39). The sort of installation that Grabar seems to suggest (in contrast to the 1975 galleries at the Metropolitan Museum) comes close in practice if not theory to the first exhibitions of Islamic art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, while certain aspects of the latest iteration of the Metropolitan Museum’s Islamic galleries also come to mind. (On the topic of the earliest exhibitions of Islamic art, see David Roxburgh, “Au Bonheur des Amateurs: Collecting and Exhibiting Islamic Art, ca. 1880–1910,” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 9–38; also see Roxburgh’s review of the Metropolitan Museum’s Islamic art galleries in The Art Bulletin 94, no. 4 (2012): 641–44, 643, where he makes a similar observation.)

In fact, among the dozen or so major collections of Islamic art worldwide, several of which have recently undergone reinstallation, the most obvious comparison with the Louvre in terms of size, scope, and significance is the Metropolitan Museum’s Islamic galleries, reopened in 2011, and renamed “Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia.” Both have a vital role to play in training a new generation of scholars and in introducing novice audiences to Islamic art and culture. With regard to the latter, both installations were specifically conceived for a post-9/11 world with the aim of helping to diminish Western misconceptions about Islam. (Whether or not this is asking too much of an installation of Islamic art or any other type of art and the degree to which such an obviously well-intentioned aim can achieve success are topics that warrant further discussion.) Both are organized along roughly the same lines, with temporal or dynastic considerations providing the main framework, although at the Metropolitan Museum visitors can see thoughtfully installed textiles and book arts shown alongside other contemporaneous objects. But at the Metropolitan Museum, the 1,200 works of art on display in 1,900 square feet are presented in a series of fifteen contiguous galleries of varying sizes, which progress through time and place in a maze-like manner. In contrast, the lack of physical barriers in the Louvre’s galleries renders less insistent the types of demarcations that art history engenders. This is not only a possible boon for the general public, for whom the finer points of organization by date and provenance are not so urgent, but for scholars as well, as it allows visitors to see Islamic art in its entirety without the strict enforcement of all the usual taxonomies and linear sequences. Another important distinction between the installations in Paris and New York has to do with their different design concepts. As already noted, the Louvre’s is sleekly and strictly contemporary without reference to the lands in which this art originated; there are no antique arcades, tile facades, or geometric patterns other than those inherent in the works of art themselves. On the other hand, the galleries at the Metropolitan Museum make dramatic use of a newly created architectural space—the Moroccan Court—and architectural elements such as mashrabiyya screens, which may provide visitors with the types of “fantasized” settings proposed by Grabar but, I think, at a great cost. Few visitors recognize that the Moroccan courtyard is a modern creation or that the mashrabiyya, at times shown in the same space as a historical one, are lately made copies. In an age when digitally constructed computer-simulations continue to alter our sense of reality and redefine the meaning of the word “genuine,” the one great constant the art museum has to offer is authenticity. In this respect, and many others, the Louvre’s new installation of Islamic art is clearly outstanding.

Linda Komaroff

Curator of Islamic Art and Department Head, Art of the Middle East, Los Angeles County Museum of Art