- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

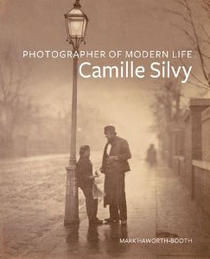

Who really was Camille Silvy? This is one of the thorny questions that remains after reading Mark Haworth-Booth’s enthusiastic biography, Photography of Modern Life: Camille Silvy. Like most commercial photographers who set up portrait studios in the 1850s, Silvy combined elements of entrepreneur, charlatan, genius, and hack. French by birth, Silvy lived in London during most of his ten years of photographic activity where he carved out a reputation based on the hundreds of cartes de visite that he successfully marketed to London’s fashionable world and on a couple of landscapes that he exhibited to much acclaim in 1859. More important in terms of his rediscovery in the twenty-first century, Silvy left studio registers with sample prints that were acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in London in 1904 which formed the basis of an exhibition held there in 2010, for which this book served as a catalogue.

In many ways Silvy’s career oddly echoes those of the other “primitives” famously profiled in Nadar’s largely embellished and nostalgic Quand j’étais photographe (1900). Born to a more respectable family than the likes of his French rival in the carte business, André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, Silvy is said to have been engaged in the diplomatic corps, but the nature of his appointments to Algeria in 1857 and his mention as a vice-consul in Exeter seem odd. To be suspicious of the seriousness of such claims, one need only recall how Gustave Flaubert, as a twenty-eight-year-old nobody, got a charge as a specialist in agriculture from the Ministry of the Interior to justify his trip with Maxime Du Camp to Egypt in 1849. Silvy, by his own account, took up wet-plate collodion photography in Algeria, not an easy task since the equipment would have been imported from France. According to Haworth-Booth, upon his return to Paris in 1858, he then studied with Count Olympe Aguado. Aguado, while supporting photography through the new Société française de photographie, was himself a student of Gustave Le Gray but does not appear to have been a teacher; Silvy, in fact, wrote in 1861 that he was “indebted” to Aguado’s counsel. Silvy’s River Scene, France (1858) and other rural landscapes are also uncannily close to Aguado’s Meudon, l’Ile des Ravageurs (ca. 1855) and Bois de Boulogne, la Mare d’Auteuil (ca. 1855), even down to their lunettes and oval-trimmed borders, as Haworth-Booth aptly demonstrated in his previous book, Camille Silvy: River Scene, France (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1992). Given that one version of Silvy’s River Scene is inscribed with a pencil annotation that identifies Félix Moutarde as the “opérateur” (normally, the person who takes the picture), and that wealthy amateurs usually had assistants, one wonders to what extent Aguado and Silvy were actively involved in making their own prints or even exposing the negatives. Certainly the lack of proof of a sustained interest in landscape on Silvy’s part suggests that the multiple versions of River Scene were experiments in combination printing (recently publicized by Henry Peach Robinson, Oscar Rejlander, and Le Gray) that bore no further fruit.

What did end up occupying Silvy was the management of a portrait studio on Porchester Terrace, which brought French carte portraits to an eager London audience. As Haworth-Booth shows, the Silvy studio style relied on unusually complicated and varied trompe-l’oeil painted backdrops and, in some cases, animated poses and figure groupings in which the space was expanded through the use of mirrors. As with all large bodies of commercial work, there is the question of how representative the seventy or so interior studio portraits and three outdoor equestrian shots before a painted backdrop that are reproduced in the book are of the 17,000 portraits recorded in the registers. Historians are inclined to favor the unusual over the routine which tends to elevate the originality of a studio owner who may never have had much to do with the portrait sittings in the first place, given the division of labor in all commercial studios, particularly those the size of the Silvy establishment. Haworth-Booth admits that after a mere three years of activity, Silvy added a partner, Auguste Renoult, and by March 1864 had ceased personal supervision of the studio.

To my mind, the most enigmatic and troubling of the photographs sold by Silvy are the smattering of genre scenes: the reenactment of the posting of Napoleon III’s order for the invasion of Italy in 1859, the view of a veterinarian’s courtyard, the three so-called Studies on Light, and the group of children gathered around potted bulbs dubbed Spring (ca. 1860). Haworth-Booth duly notes the unusual atmospheric effects in the Studies on Light series, whether achieved by multiple negatives (on page 59, Haworth-Booth cites Weston Naef’s Photographers of Genius at the Getty [Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004, 40] on this topic) or with a special lens with clarity only in its central area. He furthermore cites a letter in which Silvy envisioned adding texts and soliciting Charles Dickens’s support for the project. The contexts for such plein-air, staged views of working-class figures, according to Haworth-Booth, are the novels of Wilkie Collins and Dickens himself. However, it is striking that here Silvy makes social documents that go beyond the sentimental. For example, the hurdy-gurdy player in Studies on Light: Fog (1859) looks out with a plaintiveness unseen in the cleaned-up versions of urban poverty staged by Rejlander. One finds echoes of this clearly swarthy and stunted figure in the crippled boy in a leather cap standing to the left with a crutch in the farrier’s yard, in the profiled newsie leaning against a gaslight in Studies on Light: Twilight (1859), in the blind Afghan or Indian beggar with hand outstretched in Studies on Light: Sun (1859), and even in the young boy tending printing frames on the right edge of a high-vantage view of the Silvy studio’s courtyard. Piercing the crowd of choreographed, rag-tag workers who have been told to point toward a sunlit broadside in Reading the First Order of the Day to the army of the Italian campaign in the districts of Paris (1859) is the frontal face of a young man in a worker’s blouse glaring at the camera. To what extent was Silvy aware of the jarring address to the viewer of child workers and unruly actors in these photographs?

Even with the information preserved by Silvy’s heirs, whom Haworth-Booth has known for many years, a coherent profile of the photographer and his extremely diverse forays into genres ranging from carte portraits, to two extant still lifes (troublingly sadistic in the conspicuous nailing and binding of rabbit and bird feet), to a single panorama of Paris, to art reproductions (mentioned but not illustrated) remains elusive. Nadar’s character sketch of Silvy, while less vituperative than his castigation of Disdéri as a Bonapartist sympathizer and money-grubbing con artist, is not as positive as Haworth-Booth would have us believe: it mixes praise for Silvy’s personal grace with halfhearted references to his abilities to attract an aristocratic clientele and amass a huge fortune, which, as Nadar quipped, he knew how to spend well. Silvy’s shifting political stances—hobnobbing with the courtier Aguado, installing a room devoted to Queen Victoria in his studio, working presumably for the Bonapartist Ministry of the Interior and fighting for the emperor against the Prussians in 1870, yet supporting the exiled (and anti-Bonapartist) Orleanists in London—seem opportunistic: he is cited as joining a rifle guard in England to resist a French invasion, but gains the Légion d’Honneur in 1870 for his leadership in the Garde Mobile. His very move from France to London, perhaps only matched by that of the French-born Antoine Claudet, was strange: Disdéri, another indiscriminate portraitist of Bonapartes and Orleanists alike, established a branch operation in London, but kept his main business in Paris. To me, there is something a bit louche and ungentlemanly in the multiple reinventions of Silvy, always upwardly aspiring, dandified, even bearing a particule, “Silvy de Piccolomini,” on his tombstone in Père-Lachaise cemetery (noted in Haworth-Booth’s 1993 book but not in this one [Mark Haworth-Booth, Camille Silvy: River Scene, France, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993]).

While Photographer of Modern Life: Camille Silvy enhances our understanding of Silvy as a society portraitist, it condenses the more nuanced and documented biography in Haworth-Booth’s earlier, focused study of the landscapes. The illustrations are richer and more numerous, but the comparanda, context, and citations of original sources are minimized. Too often, Haworth-Booth recounts information but stops short of addressing what it implies. For example, in discussing a version of the River Scene that was only uncovered in 2004 and was apparently annotated by Silvy in 1875, Haworth-Booth mentions that Silvy identified the figures in the field on the right as railway workers, but fails to note the comparable identification of a seated figure on the left bank as “M Gatineau, professeur au Collège.” Of more significance, however, is how the presence of an elite academic and a group of railway workers all clearly known to and cooperating with the photographer and his operator, Moutarde, might change our interpretation of the meaning and justification of this landscape of Silvy’s hometown. Clearly, Silvy, some twenty years after making the picture, thought it worthwhile to identify these figures as more than anonymous “staffage”: because of their shared gaze at the camera, this work can be construed as a portrait of two social strata oddly gathered together for this 3–4 second exposure, which was subsequently repackaged as a picturesque view with the addition of a sky negative and hand manipulation. When Silvy (or Moutarde) told these people to gather along the l’Huisne, what did they think he was trying to do? Were these workers remnants of the opening of the Compagnie de l’Ouest rail lines to Le Mans in 1854? Was this a picture about a signal moment in the history of Nogent-le-Rotrou? These are questions that need to be asked, even though the answers are not obvious.

Biography as an art-historical method has been much under siege during the past forty years because of its failure to account for the ways that meanings are constantly adjusted through time and its emphasis on intentionality and agency which ignores the irrationality and unconscious desires at the heart of the creative process. But in a relatively young field like the history of photography, in which so little is known about the medium’s early practitioners, it still holds great sway. Much of my own career, in fact, was spent in dusty archives trying to find the barest record of a marriage, an autograph letter, or a studio inventory in order to construct an oeuvre and a life. However, in no other creative domain are the connections between the skeletal events of a career and the piecemeal leftovers of a vast, industrialized production less illuminating than in commercial photography. Silvy makes sense more as a type, whose rise and fall from wealth to insanity echo those of many of his peers, rather than a person who imprints his aesthetic and personal values on his photographs. If, as Haworth-Booth declares, Silvy’s greatest achievement was his presentation of “modern people as themselves,” then wouldn’t the successful photograph ultimately be one in which the operator disappears completely? Perhaps it was this erasure of anything more than a short-lived intersection between a lens and the world that was the truly fugitive experience that Charles Baudelaire intuited as the signal characteristic of his age’s uniqueness.

Anne McCauley

David H. McAlpin Professor of the History of Photography and Modern Art, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University