- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

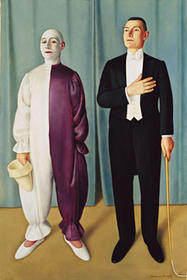

It is customary to think of European art between the First and Second World Wars in the plural—as defined by competing forms of abstraction, divergent realisms, and assorted returns to tradition. The principal goal of Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918–1936 was to assert an underlying unity to the period between the Armistice of 1918 and the Berlin Olympics of 1936. The chaos and mechanized destruction of World War I, the exhibition and its catalogue affirmed, generated a yearning for the timeless stability embodied by classical art. This provoked a widespread rejection of the formal innovations of the pre-war avant-gardes and a resurgence of interest in classicism that colored the entire interwar period.

The argument is familiar from the work of Kenneth Silver, the curator of the exhibition and main contributor to the catalogue, whose Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914–1925 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989) remains indispensable for an understanding of French art between the wars. Silver’s thesis provided the framework for bringing together a diverse and engrossing group of works, many of them unfamiliar even to devotees of the period, that evince some form of classicism. The project’s great strength lay in the opportunity it offered to examine the often-surprising congruences between works by artists from different countries and of different political persuasions operating in an overarching climate of reaction against the horrors of the Great War.

At the same time, however, such a sweeping thesis presents two significant difficulties. The first is one of definition: is it possible to elaborate a concept of classicism capable of encompassing manifestations as diverse as Pablo Picasso’s “neoclassical” works of the early 1920s, Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann’s art déco furniture, the startling realism of Neue Sachlichkeit painting, Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, and the most overtly classicizing products of National Socialist art policy (all of which were included in the exhibition)? The second is one of implication: is it possible to trace a classicizing path from the Armistice to the Berlin Olympics without suggesting that classicism is intrinsically authoritarian?

Silver addresses the first of these issues in his catalogue essay by arguing that classicism resides in a cluster of perceived values rather than a set of specific visual characteristics—and that the appeal of these values for artists lay in their opposition to the principles that had guided the pre-war avant-gardes. Thus classicism was orderly where the movements of Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism were anarchic; it was calm where they were frenetic, enduring where they were ephemeral, and so on. This comes across most clearly, Silver maintains, in representations of the human body, offered as complete, stable, and monumental after 1918 in opposition both to the formal fragmentation of the pre-war modernist movements and the physical damage inflicted on so many combatants in the war.

Such an account has the great benefit of opening the door to the splendid variety of works showcased in the exhibition, but it tends to obscure the extent of contestation over the concept of classicism in the period in question. For example, the Bauhaus was included in the exhibition under the rubric of a “modern classicism” that extends to Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. A wall label noted briefly that the school was forced to close soon after the National Socialists came to power in Germany, and the events leading up to its closure are discussed in greater detail in Silver’s catalogue essay (37–8), but the fuller implications of these events remain unexplored. The National Socialists, who would soon espouse—for their monumental public sculptures at least—a form of classicism devoted to representing the hyper-muscular male body, were careful to stamp out competing claims like those of modernist architects, who rooted their form of classicism in Platonic idealism. Seen in this light, classicism becomes less a unifying force than a battleground.

The concept of the “modern classic” is further explored in James Herbert’s catalogue essay, which focuses on developments in France between the wars. But Herbert’s elegant visual analyses of works by Fernand Léger and Henri Matisse never quite add up to his conclusion that the two artists were trying “to establish calm corners of the modern classic that could offer respite following the terrible chaos of the war” (143)—a conclusion that seems to strain to fit the wider theme of the exhibition. Writing about the situation in Germany, Jeanne Anne Nugent also seems torn between a desire to do justice to the diversity of artistic production shown in the exhibition and a concern to unite that production under the theme of classicism-as-common-denominator.

Indeed, it is hard to argue that movements like Neue Sachlichkeit and its offshoot Magic Realism, with their quasi-photographic verisimilitude, are classical, even if in 1925 the German critic Gustav Hartlaub did characterize a group of Munich-based artists around Georg Schrimpf as “equal to Classicism” (cited by Silver in the exhibition catalogue, 24). Schrimpf’s works of the 1920s may have aspired to a kind of timelessness that fits with a broad definition of classicism, but their more obvious formal influences can be found elsewhere. Women on the Balcony of 1927, which represented the artist in the exhibition, shows two women seen from behind (in what seems an overt reference to Caspar David Friedrich), surveying a landscape familiar from endless Northern Renaissance paintings. The trajectory into which it fits, therefore, is a specifically Northern European one, constituted quite separately from Mediterranean classicism, that was evoked deliberately by many German artists before and after the First World War.

The point is worth making because it is the slightly later attempt to meld this northern tradition of realism with a more conventionally construed, idealizing classicism that makes many key Nazi works so disconcerting. Adolf Ziegler’s Four Elements of 1937—in its horribly mesmerizing way certainly one of the highlights of the exhibition—offers exactly this combination of sculptural, idealized figures with the kind of meticulous attention to specific facial and bodily details that earned the artist the nickname “Reich Master of the Pubic Hair.” By treating these distinct tendencies under the sole rubric of classicism, the exhibition tended to elide the distinction between classicism and the broader category of tradition. Silver was clearly aware of this risk: he notes in his catalogue essay that the Four Elements does not “look especially Greek or Roman” (46), and elsewhere he describes what was going on between the wars as “a real or imagined return to tradition, national styles, and classicism in its various permutations” (22).

Nonetheless, the exhibition was assembled under the banner of classicism, rather than of tradition more generally, and this affected the impression it generated. It is always hard to set aside the ideological associations of classicism, which has, as Henri Zerner suggested, a historical role as “the art of authority” (“Classicism as Power,” Art Journal 47, no. 1 [Spring 1988]: 35–36); it was particularly difficult to ignore these associations as one experienced Chaos and Classicism physically at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Visitors circled up the famous ramp in a more-or-less chronological progression, stepping off into a side room to see the products of “modern classicism,” then resumed their upward progress to arrive at a climax (of sorts) in the final room, devoted to classicism under Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany. I found it all but impossible to escape the implication that the various faces of the interwar classical revival all had their quotient of authoritarianism, and that all were somehow linked to the rise of Fascism; much of the critical response to the exhibition registered a similar reaction.

The catalogue certainly sets out to complicate, if not contest, this view. Silver’s essay devotes space to manifestations of classicism on the political left, as well as to works like Hannah Hoch’s Rome (1925) that deliberately sent up classicism’s supposedly lofty ideals. In both cases the intention seems to be to break up the impression of an onward march toward Fascism by emphasizing the variety in classicism itself and in the responses with which its revival met. Emily Braun’s essay on interwar Italian sculpture, too, is notable for the subtlety with which it treats the relationship between traditional content and technique and Fascist politics. Her main focus is the work of Arturo Martini, and her conclusion that, “precisely because of its ironic play with historical references, Martini’s work complicates the easy equation of a return to tradition with the avant-garde’s loss of originality and capitulation to authoritarian politics” (146), would have served as a useful watchword for the exhibition as a whole. For ultimately, works that contest the idea of classicism as inherently reactionary, and the texts that discuss them, are dispersed throughout the exhibition and the catalogue in a way that makes them very difficult to assemble into a counter-narrative—whereas Silver’s essay, like the exhibition itself, seems to build toward a conclusion, even a culmination, as it approaches its final section, which deals with classicism under the Fascist dictatorships.

As a result, for all its diversity, the exhibition tended to reinforce an existing art-historical trope. The idea of all the “returns to” of the interwar period as authoritarian goes back to Benjamin Buchloh’s essay “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation in European Painting” (October 16 [Spring 1981]: 39–68); and the exhibition ends up replicating, rather than critically engaging with, Buchloh’s propensity for tarring all forms of anti-modernist reaction with the same brush. Whether you unapologetically lump together all returns to representation, manifestations of classicism, evocations of tradition, and declarations of the importance of craft, as Buchloh does, or whether you develop a conception of classicism so capacious that it can accommodate all those tendencies, as Silver does, the result is to homogenize the art of the interwar period.

It feels churlish to accuse an exhibition that brought together such a broad collection of works, many of them little-seen, of the intent to homogenize, and I think this points to a mismatch between the works themselves and the interpretative framework into which they were placed. Faced with an array of works showcasing the variety of returns to figuration and references to tradition that characterized the interwar period, I would have liked to see the range of motivations that impelled artists to adopt these strategies more expansively and less tendentiously treated.

Toby Norris

Assistant Professor, Department of Art, Music and Theatre, Assumption College