- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Though Anne Truitt’s art has not shaped art-historical and critical debates at the level of many of her contemporaries, whether Morris Louis, Robert Morris, Eva Hesse, and others, her work warrants all the attention the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden devoted to her in this retrospective exhibition, Anne Truitt: Perception and Reflection. Curated by Kristen Hileman, it included drawings, paintings, and sculptures by the artist from the early 1960s to 2004, the year of her death.

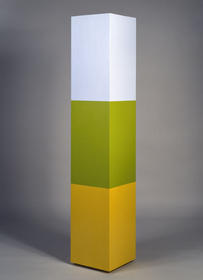

The Hirshhorn installed Truitt’s art chronologically, which highlights how she rather quickly discovered and, with few exceptions, persisted in pursuing what would become her signature form: a painted four-square columnar or pillar-like form averaging around six feet in height. The comparison to a column is potentially misleading because the sculptures are clearly not in any way intended to provide architectural support. Truitt underscored the works’ status as an autonomous artistic object when in the 1960s she lifted the sculptures an inch or so off the floor by a recessed supporting structure invisible to the viewer when both the sculpture and viewer are standing erect. There are many variations on this columnar-like form—sometimes they are wider, sometimes shorter or taller, sometimes they have a protruding extension, and occasionally the sculptures are designed to lie horizontally and parallel to the ground. As a necessary security and conservation measure, the Hirshhorn displayed Truitt’s sculptures on low-level platforms; the tradeoff is that this display technique reduces the physical and visual intimacy between aesthetic object and viewer and makes the sculptures appear more aloof than they otherwise would be.

Given Truitt’s commitment to geometric forms stripped of ornament, her sculptures would seem to fit neatly into the Minimalist camp. Indeed, Truitt participated in the exhibition Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculpture at the Jewish Museum in 1966, which included artists commonly associated with Minimalism, among them Robert Morris and Donald Judd. Yet, in painting the sculptures pink, baby blue, orange, black, and so forth, or in painting them with bands of color, Truitt transformed the wooden surfaces into a field of sensuous color. In this respect, it is significant that she studied briefly with the Washington Color Field painter, Kenneth Noland, and visited Morris Louis’s studio. In the end, Truitt merges two positions in art that we otherwise understand as radically opposed: Minimalism and Color Field painting. Whether or not merging seemingly irreconcilable differences was her intention (and it clearly was not) is immaterial; from an art-historical perspective, this is one of her most significant achievements.

Truitt had a strong desire to be a painter and sculptor concurrently, approaching a single artwork as both two and three dimensional. Early works such as Watauga (1962) and Hardcastle (1962) make this explicit. Both pieces consist of a smooth, painted panel positioned upright and, as in the case of Watauga, supported by a base, or, as in the case of Hardcastle, braced by two long diagonal slabs of painted wood attached to the back. Although both works consist of a panel that calls attention to itself as flat and frontal, they also invite the viewer to move around them to see their sides and backs. As early as 1962, Truitt conceived of what would become her principle structure, the four-square columnar form, in which no single side can be said to constitute the front or back. Truitt discharges the sculptures of a primary vantage point when she paints each of the four sides in a similar tone or with bands of different colors of varying width. In the later case, when no one side is the same, each side is individualized, which the viewer only discovers by walking around the sculpture, producing an unpredictable, temporal, and non-literary “narrative” experience. (“Narrative” is Truitt’s word choice to describe this effect.) The viewer of the Hirshhorn show is able to experience this phenomenon most fully when Truitt’s sculptures are isolated (rather than grouped closely together), permitting the viewer to walk a full 360 degrees around them.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue with an essay by Heilman and art historian James Meyer. Museum catalogues are an important venue of art-historical research and knowledge for the reading public, and it is incumbent upon museums to enlist the most adept curators and scholars to write for them. On this point, the differences in Heilman’s and Meyer’s essays are striking. In her essay, Heilman weaves together commentary on Truitt’s art and life, quoting extensively from Truitt’s prolific journals, and generally accepting the artist’s every word as truth. The main problem with the essay is that there is no overarching thesis and argument or, at least, not a convincing one. Hileman wants to develop a conventional “iconography” of Truitt’s work based on the artist’s life and thought. Although Truitt’s art is as abstract as art can be, Heilman wants the viewer to see references aplenty, so that each shape and color possesses some personal meaning and association in Truitt’s life. (Truitt’s art is “inextricably linked to life” (43), she concludes.) This is a familiar and, in this case, flawed methodology. In an early sculpture, First (1961), a sculpture in the form of a low picket-like fence, Heilman searches endlessly for referential clues, concluding at one point that the three pickets “expand the work from a consideration of the concept of boundaries to a depiction of three joined but distinct entities, perhaps not without parallels in the relationships among Truitt and her two siblings” (14). Hileman is essentially asking that the work be seen as representing Truitt herself (via the tallest post) and her twin siblings (the two smaller posts on either side). This kind of literal association is not always helpful in understanding Truitt’s art, and at a certain point its defective character becomes clear: If the two shorter posts on either side of the taller one represent Truitt’s younger twin sisters, why are they unequal in width?

James Meyer’s essay is a well-written and probing instance of interpretative art history. Meyer begins with a description of A Wall for Apricots (1968), demonstrating how it alludes, abstractly, to the body, invoking a “somatic perception.” To my mind, this introductory point is the most questionable one in his essay, not because this type of sculpture-body analogy is so frequent in the scholarship on Minimalism; rather, as a viewer, I experience just the opposite. Because Truitt’s immobile sculptures follow so severely the logic of the right angle, her works insist on their difference from the flaccid, curvilinear, and anxious human body. In any case, Meyer does not pursue the body analogy at length in the rest of his essay, and therefore it does not seem central to his primary argument.

Instead, Meyer argues convincingly that whereas other Minimalists sought to purge their work of allusion, Truitt sought “to maximize, to condense, to add” (54; emphasis in original). Quoting from Truitt that all her life she aimed to gain “maximum meaning in the simplest form,” Meyer builds his analysis around Truitt’s remark, adding that the artist’s “negotiation of this ration is the crux of Truitt’s ambition.” To illuminate the significance of this measure, Meyer demonstrates why Truitt abandoned the disjunctive, asymmetrical sculptures she produced during the mid-1960s when she was living and working in Tokyo and committed her work rigorously to the columnar structure. The Tokyo works were “‘maximum’ sculptures yet their forms were not the simplest they could possibly be,” Meyer explains, adding that the column, on the other hand, was truly a “‘simplest’ form, a form so simple it could sustain a synecdochic dilation of meaning” (60). The terms at the end of this quote are central to Meyer’s analysis and methodology. He draws upon his study of linguistics to demonstrate that Truitt’s decision to employ the four-square column is an instance of a “synecdochic pursuit,” meaning that the column is a part that represents the whole and thus is “capable of eliciting the most associations because it is so reduced” (60; emphasis in original). On this point, the difference between Meyer’s and Heilman’s methodology becomes evident: Where Meyer aims to reveal how the sculptures operate formally and semantically in producing meaning, Heliman instead seeks such meaning in literal parallels to the artist’s life.

Robert E. Haywood

Robert E. Haywood, Deputy Director, Contemporary Museum, Baltimore