- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The Japanese term surimono refers to privately commissioned prints intended for circulation to a limited group of individuals in connection with some special occasion or significant event. As such, they reflected the interests of the groups to which they were sent, and they almost always differed in distinctive ways from contemporary commercial prints put out by the same publishers. There are a number of features that set them apart. One is the expensive pigments and meticulous techniques employed in their printing. Another is that most—though not absolutely all—bear poetic inscriptions. This is a feature that surimono share with numerous earlier Japanese (and Chinese, for that matter) pictorial works, a point underscored in several of the essays in Reading Surimono as well as in the choice of the book’s title.

Though the genre first appeared in the late eighteenth century, its heyday was in the first half of the following century. Though some surimono were published in the Kyoto-Osaka (Kamigata or Kansai) region where most of them were designed by artists of the Shijo school, the vast majority were published in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and designed by ukiyo-e artists; and it is the latter that are the subject of Reading Surimono.

The ukiyo-e art style originated in Edo and came to be so closely identified with that city that ukiyo-e prints were often called Azuma nishiki-e, “brocade pictures of the East,” the “East” being the part of Japan dominated by Edo. Today ukiyo-e is best known outside Japan for prints of the sort exemplified by Utamaro’s sensuous portrayals of glamorous courtesans and Hokusai’s memorable views of Mt. Fuji—prints that, unlike surimono, had been commissioned by publishers for public sale. Yet ukiyo-e artists also created paintings, illustrated books, and designed surimono at the behest of private patrons. Until quite recently, however, these other genres received relatively little attention.

That this was true of surimono, which, after all, are prints, may seem surprising, and they did find their way into some ukiyo-e print collections. But even in such cases they seem to have been included almost as an afterthought, more for the sake of inclusiveness than for themselves. Given their smaller format and more complex compositions, not to mention the somewhat distracting presence of the calligraphic inscriptions, it may be that they were perceived as not capable of competing with the bolder compositions and more immediately striking designs found in the more common commercial prints. Moreover, the inscriptions themselves meant nothing to the collectors, since virtually no one in the West (and very few even in Japan) could translate them.

In the 1980s, however, these attitudes began to change. Independent scholar Roger Keyes and the Dutch curator Matthi Forrer began publishing some of the most serious work on the genre to appear in generations. Then, a decade later, in 1995, an even more significant sign of change occurred when Joan Mirviss, collaborating with John Carpenter, produced her groundbreaking The Frank Lloyd Wright Collection of Surimono (New York and Phoenix: Weatherhill and Phoenix Art Museum). That publication was soon followed by others, by both the same as well as different authors, and today there can be no doubt that surimono have finally begun to assume an honored place in the larger world of ukiyo-e artistic expression. No better proof of this could be offered than Reading Surimono. Brought out by the respected Dutch scholarly publishing house Brill under its Hotei imprint, which specializes in books on Japanese art, with ukiyo-e as one of its primary focuses, it is a weighty volume, both literally, at 432 pages, and in every other sense of the word.

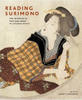

The old adage, “never judge a book by its cover,” notwithstanding, some books do convey a strong sense of what they are about before they are opened, and Reading Surimono is one of them. The arresting image of a kimono-clad woman seemingly looking up at the book’s title on the jacket cover gives a foretaste of the confident, meticulous sense of design evident in every detail of the publication. It is also an ambitious work. The publishers describe it on the jacket cover as a “groundbreaking scholarly publication,” and it is.

There would be something ironic about describing this book as an instance of the changes in the way surimono are now being regarded, because those changes are, in fact, largely the product of the kinds of research it embodies. Carpenter, the book’s editor, has been at the forefront of surimono studies for the last ten years or more, and by concentrating on the poetic inscriptions and the interplay between these poems and the imagery created to accompany them has brought modern appreciation of the expressive possibilities of these unique prints much closer to what was experienced by the public for which they were originally intended.

The key to this achievement is Carpenter’s wide-ranging familiarity with Japanese pre-modern literature and with kyoka—the type of verse most often inscribed on Edo surimono—in particular. There is a wide gulf between modern Japanese and the relatively archaic form of the language employed in Japanese literature prior to the Meiji period (1869–1912), which even many contemporary Japanese find difficult to translate. The language used in kyoka, which abounds in homophones and is often densely allusive, is even more challenging, and until quite recently few Westerners could master it. Carpenter, who began his academic life as a Japanese literature scholar, was one of the first to do so, and his translations remain among the most admired in the field.

One needn’t delve far into Reading Surimono to realize just how much the availability of such translations can add to the understanding and appreciation of the prints. The book offers numerous examples where imagery that might at first glance seem either whimsical or obscure is suddenly suffused with meaning once the poetry is taken into account, or where a scene that appears perfectly straightforward on the surface is transformed through the prism of the accompanying poems into an evocation of passages from classical Japanese or Chinese literature. In both cases—and in fact in almost every surimono—the poetry and imagery do not simply exist side by side but are integral to one another. The imagery never exists solely as a foil or backdrop for the poems, even though most Edo surimono were commissioned by kyoka clubs to commemorate and draw attention to the poetic accomplishments of their most gifted members. All this gives a clever and somewhat ambiguous twist to the title, Reading Surimono. One cannot understand the prints without reading the poetry (at least in translation), but one cannot understand the poetry without picking up on the nuances and allusions provided by the imagery; in other words, one can only fully “read” the imagery after having read the poems.

Calligraphy and painting have been closely linked in East Asia for centuries, a tradition that has resulted over time in the appearance of many art forms combining written words and images in ways totally different from anything found in the West. Seen in this light, the combination of text and imagery encountered in surimono is simply another example of—or, perhaps more accurately, another variation on—earlier practices. Yet never, to my knowledge, have the two been as completely conjoined as they are in surimono, where they often become, in effect, two essential components of a single whole. A conviction that this is in fact the case—that discovering the specific interplay between poetry and imagery in any individual surimono is essential to the work’s appreciation—is a recurrent leitmotiv in Reading Surimono, the subtitle of which, after all, is The Interplay of Text and Image in Japanese Prints.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that this is all that the book is about. It begins with a series of essays by a diverse set of specialists in Edo-period Japanese art and literature, each of whom brings a unique perspective to her or his topic. The subjects range widely, from Carpenter’s examination of the often recondite ways poets and artists drew upon and transformed classical subject matter for use in their work to Tsuda Mayumi’s report on her discovery that a hitherto unidentified commissioner of surimono was actually a highly placed regional lord, to cite just two examples. Other discussions range from Kobayashi Fumiko’s description of how surimono could be used to bolster the prestige of certain kyoka club masters to Mirviss’s review of the market for surimono in pre-World War II Paris and the pitfalls and opportunities it offered would-be collectors. For many readers, these essays, which take up much of the first third of the book, will be the most interesting part of the publication. But the second—and much larger—part of Reading Surimono is devoted to a catalogue of an important, previously unpublished Swiss surimono collection. Assembled by Marino Lusy (1880–1954), a print artist and somewhat elusive figure about whom little is known, the collection was bequeathed to Zurich’s Museum of Design but is now on permanent loan to the city’s Rietberg Museum where it can be exhibited in context with that institution’s other rich holdings of Asian art.

This section, which could easily have been an independent volume in its own right, represents an impressive scholarly achievement in itself, and some may question why it was not treated as such. Two of the twelve essays relate directly to the Lusy collection, however; and most of the others illustrate their arguments with examples from it. The result is a book able to attract a much wider readership than a traditional collection catalogue, which would primarily be of interest only to a fairly limited group of scholars and collectors.

Though Carpenter is listed simply as editor, his central role in the book is apparent in almost every aspect of the publication. Clearly it was he who recruited the other contributors, all of whom are either his students or his associates and colleagues. His general introduction and subsequent essay are among the most illuminating contributions in the first section of the book; and—not to downplay the valuable assistance he received from several colleagues and students—he is clearly the primary author of the catalogue section, which I have already characterized as an impressive scholarly achievement in its own right.

It catalogues 294 prints arranged in alphabetical order by artist, with succinct biographies of every artist preceding the sections devoted to their work. Each print is handsomely reproduced in color and provided with all the customary catalogue information (title, date, dimensions, provenance, etc.), then described in terms of its (sometimes arcane) subject matter and the interplay between the poetry—all of which is translated and explained—and the imagery. The layout has none of the cramped look often found in collection catalogues, and the generous space devoted to each print, sometimes as much as two pages, makes perusing this section of the book a pleasure.

The book concludes with a list of provenances of the Lusy collection, a selected bibliography, a comprehensive index of kyoka poets (with their names in kanji as well as roman letters), and a general index, all of which add significantly to its usefulness.

In the West in general but especially in the United States, ukiyo-e was late to be considered a legitimate field for scholarly research. Until the 1970s, most publications on the subject were written by collectors or dealers whose connoisseurship was admirable but whose knowledge of Japanese art outside their narrow specialty was limited. This is no longer the case, as Reading Surimono makes abundantly clear. In fact, in the extent to which it draws on contributions by both Japanese and Western specialists it goes well beyond what is seen in most other Japanese art-history projects. It provides an example of the kind of international collaboration that will increasingly enrich the quality of scholarship on both sides of the Pacific.

Donald Jenkins

Curator Emeritus of Asian Art, Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon