- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The Eight and American Modernisms was the latest exhibition that sought to find some kind of unifying thread to bind together eight artists—Arthur B. Davies, William Glackens, Robert Henri, Ernest Lawson, George Luks, Maurice Prendergast, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan—whose formal association lasted roughly a year and whose art has bedeviled the efforts of art historians to assess the importance of their contribution, collectively or as individuals. When the artists banded together in 1908 to exhibit their paintings at the Macbeth Gallery in New York, they were linked more by friendship than by any overarching stylistic or aesthetic program. Some (Glackens, Luks, Shinn, and Sloan), who lately had gained attention as painters of the “urban scene,” were erstwhile students of ringleader Henri, though comrades is perhaps more accurate, for none had studied with him in a formal sense for any sustained period. And while Henri had made a name for himself as a spokesperson for the “younger” generation of independent-minded artists in New York, all of “The Eight” were veteran exhibitors who already had made firm steps toward establishing successful careers. Scholars generally now agree that the 1908 exhibition was above all a shrewd marketing device, yet another in the series of the “secessionist” exhibitions effectively used by European (and American) artists since the 1850s.

Elizabeth Kennedy, Curator of Collection at the Terra Foundation for American Art, who coordinated the exhibition project, and her colleagues from the Milwaukee Art Museum and the New Britain Museum of American Art were constrained from the start by their decision to assemble works from only these three collections. These institutions do boast generally fine examples that span the eight artists’ careers. However, this selection meant that the artists were represented by purchase decisions made by disparate collectors and curators, not by works the artists themselves might have considered their best or most representative. It also means that, within the exhibition installation, the significance of the 1908 gathering was curiously mitigated because no wall labels fully explained the circumstances of the 1908 exhibition (and tour) or identified works therein included. Similarly, The Eight and American Modernisms included drawings and prints by all eight artists, though only Prendergast showed works on paper at the 1908 show. Granted, the exhibition was trying to move beyond the artificiality of the 1908 association, but the facts of that gathering should still have been more fully accounted for.

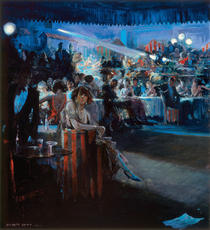

This reviewer saw the exhibition at the New Britain Museum of American Art, where it was installed in the capacious special exhibition gallery of that museum’s new wing, designed by Boston-based architects Ann Beha and Associates. However, the installation reinforced the weaknesses of the exhibition and its concept. Though freestanding wall panels allowed for fluid movement in and around the show, each artist was given his own section (arranged alphabetically), and no attempt was made to set up visual connections or contrasts among the objects. Because of the three-museum focus, the chronological range of works by each artists differed, and so it was difficult, simply by touring the exhibition, to see any larger questions or connections that might have explained the conceptual purpose of the exhibition. Wall labels were few in number and offered somewhat simplistic, formalist commentaries, again leaving visitors at a loss to explain the significant stylistic and thematic changes reflected, say, in Glackens’s works as opposed to the more homogeneous-seeming works of Lawson. When this reviewer visited, a docent was valiantly trying to explain Glackens’s debt to Impressionism while standing before the artist’s intriguing Bal Bullier of 1895. This small, vigorously brushed study of dancers in the dark, smoke-filled spaces of a celebrated working-class Parisian café surely owes more to the work of James McNeill Whistler, or even Edouard Vuillard, than any “Impressionist.”

Kennedy states in the catalogue’s introductory essay that the aim of The Eight and American Modernisms was to “reclaim these individual artists’ contributions to this tumultuous era when progressive art of all tendencies was vying for attention” (14). Kennedy rightly faults the tendency among much American art historiography to dismiss the continuing activities and influence of “The Eight” after the landmark 1913 Armory Show. She also challenges the several recent exhibitions and monographs that have focused overmuch on the urban realism practiced by some in the group, too often dubbed the “Ashcan School.” Instead, Kennedy asserts, the history of “The Eight” is “a far more complex tale, for each artist experienced a successful professional journey that defies group labeling, with its implication of a single unifying ideology or static artistic outlook” (14).

Point taken. But we have to turn to the catalogue to find any sustained discussion of these aims. The volume is an impressive product with numerous accurately printed color illustrations. Though available only in hardcover, it is reasonably priced. As is standard practice with exhibition catalogues nowadays, Kennedy (who also wrote the essay on Prendergast) invited contributions from six other scholars who had published previously on these artists or their milieu: Peter John Brownlee (Glackens), Leo G. Mazow (Shinn), Kimberley Orcutt (Davies), Judith Hansen O’Toole (Luks), Sarah Vure (Henri and Sloan), and Jochen Wierich (Lawson). It is interesting to note that some of the contributors are curators at institutions that own important works by members of “The Eight,” yet the exhibition was not expanded to reflect this. It is also curious that no essays were contributed by the staff of either the Milwaukee Art Museum or the New Britain Museum.

All of the contributors attack the question of what “modernism” meant to these eight men. They effectively use the works in the exhibition to demonstrate that all of these artists continued to engage with what they considered progressive approaches throughout their careers, whether Davies’s short-lived experiments with Cubism, Henri’s ongoing exploration of color theory, or Shinn’s witty adaptations of the rococo in several mural projects. We learn too about ongoing friendships and professional collaborations, as with Glackens and Prendergast, or Lawson and Luks, or Davies’s work as the organizer of important avant-garde exhibitions into the 1920s. The contributors also remind us that several of these men were teachers—Henri and Sloan in particular maintained active and influential careers.

Still, this reviewer looked in vain throughout the catalogue essays for a rigorous critique that effectively confronted how each or any of these artists negotiated (accommodated? rejected?) the still considerable influence of European art styles and practices. Instead the contributors persist in holding onto the myth that these artists contributed a spirit of independence and “individualism” to the American arts community, without considering how that independence was built upon the calculated adaptation of European ideas. Even Henri’s rough-and-tumble masculinity was derived from the boyish antics traditional in French ateliers. The contributors’ disinclination to confront the Americans’ obvious debt to things European affected the entire project. How can we gauge the artists’ “individualism” when we are given no sense of the opposite? Where is the “progressive art of all tendencies” that might provide some comparison and perspective?

So the visitor is left to ask yet again: What did bring these men together and what do we learn about them as painters and thinkers from the works on view? In effect, the exhibition offers eight mini one-man retrospectives. The organizers subscribe to the “heroic” story of American modernism and rely on Henri’s rhetoric or that of various critics and biographers to glue these artists together. If these artists were so important, why must they always be treated collectively? Why do museums seem hesitant to organize substantial monographic retrospectives on, say, Davies or Glackens or Shinn? How do we deal with the prevailing, if typically unspoken, opinion that works by these artists, with the possible exception of Prendergast, were frustratingly uneven? Throughout his career Henri, for one, despite his forays into color theory, made no significant innovations as regards the apprehension of form or the formulation of new iconography in his painting. His principal contribution, as an inspiring teacher, as well as gadfly, seems to have been primarily rhetorical—he persuaded his contemporaries that a flat Midwestern twang was just as effective as a suave Parisian lilt. In her introductory essay, Kennedy quotes Bruce Altschuler, who ventured that the modernity of “The Eight” derived from their breaking with the sentimentality of the nineteenth century and their “focus on individual expression” (15). Yet how do we account for the increasingly sentimental imagery of Glackens, or even Luks? The theme of individualism is echoed by all of the contributors, yet this is difficult to define among artists who held tight to an essentially conservative approach to representation. Indeed, one theme that runs through the essays is the increasing isolation that many of these artists embraced, or suffered, as they aged.

“The Eight” were not America’s “high modernists.” Rather they were master manipulators who used the popular media to insert themselves into the linear mythology of modernism crafted by European artists and critics, a mythology that much recent scholarship has begun to disassemble. Indeed this reviewer made this argument almost twenty years ago in an exhibition catalogue that is oddly absent among citations in this publication. What we really need now is a rigorous exploration of the artists’ fundamental conservatism. The most thought-provoking illustration in the catalogue, though mentioned only in passing in Kennedy’s essay on Prendergast, is Ad Reinhardt’s 1946 “family tree” of American modern art. The cartoon shows a sturdy mature tree sprouting from roots labeled Cézanne, Seurat, Gauguin, Van Gogh. Onto the trunk are carved the names of European modernists, led by Braque, Matisse, and Picasso. The tree’s leaves, not its branches (implying ephemerality?), are inscribed with the names of a considerable number of younger American artists and some older colleagues—Pollock, Bearden, Rothko, Masson, Gorky, McIver, Dove, Masson, etc. One main branch, however, is breaking away from the main trunk, literally pulled down by lead weights tagged “subject matter,” “nudes,” “regionalism,” even “Mexican art influence.” And it is among the leaves on this branch (with Hartley, Sheeler, Evergood, Hopper, and many others) that we find only one member of “The Eight”: very close to the lead weights is a leaf labeled Sloan. By 1946, Sloan’s erstwhile comrades all were dead. And with his death in 1951, the leaf quickly fell from its branch.

Elizabeth Milroy

Professor, Department of Art and Art History, Wesleyan University