- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

In his introduction to the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Paint Made Flesh, curator Mark Scala writes that the show seeks to trace a history of “the depicted body as a metaphor for the relationship between self and society as it has changed throughout the decades following World War II” (1). It does so admirably, if incompletely, and without making the recalibrations to larger understandings of postwar painting that seem to be its latent promise. As such, it is an exhibition both wildly pleasurable and quietly frustrating, leaving viewers with the sense that the magnificent group of works is something of a consolation prize for the missed opportunities of what could have been a substantive, thrilling challenge to many of the orthodox histories of postwar art.

First, however, there are the paintings, which are absolutely spectacular. Scala has done a superb job of bringing together a sensibly sized yet diverse group of works. It is a group comprised mostly of blue-chippers: Pablo Picasso (still in his role as godfather of everything), Willem de Kooning, Leon Golub, Alice Neel, David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, Philip Guston, Julian Schnabel, Susan Rothenberg (hands, not horses), the most glorious Karel Appel I have ever seen (the Hirshhorn’s 1963 Beginning of Spring), A.R. Penck, the first Georg Baselitz that has truly stunned me (the Albright-Knox’s 1976 Nude Elke 2 (Akt Elke 2), Francesco Clemente, Eric Fischl, Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, Frank Auerbach, and Leon Kossoff (whose presence in our histories clearly needs amplification). They are joined by the newest members of this cadre—Jenny Saville, John Currin, Lisa Yuskavage, Cecily Brown, and Michaël Borremans—and recent contenders such as Daniel Richter, Albert Oehlen, and Wangechi Mutu. Conspicuous were the absences of a number of painters who seemed perfect for such a gathering: Jean Dubuffet, Glenn Brown, Luc Tuymans, Jean Fautrier, Renato Guttuso, Andre Fougeron, Gerhard Richter, Beauford Delaney—any of these would have been a welcome addition and would have beautifully complicated the already assembled group. The included artists were a broadly diverse and representative group, but one that felt a bit expected, as if challenging the current canons of both art history and the art market might be too great a leap.

This is the central conflict of Paint Made Flesh. Visitors who are already versed in the history of figuration in the twentieth century will inevitably find gaps in and problems with a show that takes such a broad and diverse topic as its focus. Those with less familiarity will be greatly delighted and surprised by many artists who still are not well known to a general audience.

To its credit, Paint Made Flesh works hard to make sense of the trends it seeks to explore. Divided into five spaces—American Art: 1952–1975, Neoexpressionism, Beyond Portraiture, British Painting: The Traumatized Body, and History Today: Fragmentation and Reconstitution—the exhibition seeks commonality, and, in doing so, offers something of a coherent vision of how the body has been handled by artists during the past five decades. Naturally, certain areas are more cohesive than others.

The first room, of American painting, is emblematic of both the strengths and weaknesses of the exhibition. Hung at the end of the room and occupying the whole of its own wall, Golub’s huge 1961 canvas Burnt Man IV is absorbing and visceral, but simply too strong for other works in its vicinity to garner much attention. The rent flesh of Golub’s figures makes much sense near Hyman Bloom’s autopsied corpse in The Hull (1952) or juxtaposed with the psychological depth of Neel’s 1960 Randall in Extremis, but the precision kaleidoscopics of Ivan Albright’s 1966–77 The Vermonter (If Life Were Life There Would Be No Death) or the modestly sized 1957 Male Nudes at the Water by David Park are overpowered. The grouping is all the more peculiar as works by Bacon are hung three rooms later, literally out of sight, probably out of mind. Here, one begins to wonder if the ways in which the exhibition is divided by room might not be an impediment to realizing similarities across geographic or temporal boundary. Unfortunately, it is hard to miss these missed opportunities.

The rooms of Neoexpressionism and British Painting hold together best, with their temporal and geographic binders, but these groupings are not favorable for all. German painting of the 1980s—particularly that by Markus Lüpertz and Baselitz—is much more convincing than its U.S. counterpart. Moreover, the presence of a 1960s Appel is somewhat perplexing. The chosen hanging, with its genealogical emphasis, is not without merit, but the temporal and geographic differences are difficult to reconcile. While Appel, with CoBrA, was fundamental to the development of the postwar European abstraction that so influenced the Neoexpressionists of the 1980s, the pairing feels nonetheless forced. Why, instead, do we not find Appel near De Kooning (another Dutchman rigorously testing the boundaries of abstraction and figuration) or his British contemporaries exhibited in the following room? Again, the works seem constrained, rather than illuminated, by the show’s divisions.

The room of British Painting appears bound by its collective national heritage alone. Freud’s nudes, with their awkward, self-conscious psychologies, pair beautifully with Bacon; but their commonality with Brown’s porn- and landscape-inspired Figures in a Landscape 1 (2001) or Saville’s 1999 Hyphen appears limited to a circumstantial combination of England, bodies, and loose paint handling, a frustrating reduction of the nuances that differentiate these artists.

The other two spaces are likewise troubled. It is somewhat unclear how Beyond Portraiture actually leads viewers beyond portraiture. Currin’s 1999 The Hobo offers his usual blend of seduction and revulsion—all curls, pendulous breasts, and under-fed, rosy-cheeked Mannerist attenuation. Yuskavage’s 2003 Babie I is a welcome departure from the cotton-candy and doe-eyed vacuity of much of her recent production. It is always amazing how these qualities are so much more captivating in painting than in the endless stream of Hollywood ingenues. Certain works in this room are quietly remarkable, with Tony Bevan’s 1992 Self-Portrait and Fischl’s 1996 Frailty is a Moment of Self-Reflection as noteworthy successes, the latter suffused with a sickly yellow light that beautifully redoubles its creeping, isolated sense of mortality. Too bad that the room also includes Clemente’s 2002 Self-Portrait with Two Heads, which is too coy for its own good and, frankly, looks cheap and unskilled next to its neighbors.

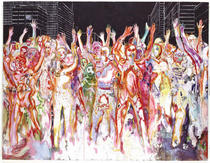

Likewise, History Today: Fragmentation and Reconstitution feels cobbled together. Maybe it is anathema to exclude the most contemporary of contemporary artists, but the results of this ensemble are somewhat underwhelming. Oehlen, who is usually so satisfying, is less so here, with his 2002 The Goal-Kick (Der Torschuss). Mutu’s 2004 Squiggly Wiggly Demon Hair presents the greatest complexity. Her sliced, diced, and collaged interrogations of self and place are compelling, but we can almost see her being commodified as the post-national archaeologist of self du jour. For all her compositional and intellectual agility, one wonders if the absorption of her work by the machinery of market and academy won’t end up blunting what edge it may have. Conversely, Richter’s 2004 Duisen is a revelation. It never seemed possible to combine James Ensor, Jackson Pollock, Sebastiano Serlio, Day-Glo, and the YMCA dance, but Richter has done so magnificently, offering an apocalypse in progress, Midtown meets ghouls gone wild, and a potent send-off.

If there ever was an exhibition where shortcomings double as strengths, Paint Made Flesh is that exhibition. Its ostensible goal, exploring “artists of three generations whose depictions of the human figure denote biological, psychological, and spiritual volatility” (1) is effectively accomplished. Where the exhibition falls short—in its often traditional dealings with individual works, reductive or seemingly arbitrary groupings, and a dependence on artists about whom much is already known—we see a reflection of the larger discourse surrounding this topic. Although much has been done to loosen the stranglehold of certain methodological orthodoxies (Greenbergian Modernism; the ongoing tendency to “read” “texts” instead of look at paintings; and the lingering, false presumption that figuration is a lesser participant in postwar art), many of these have remained, as evidenced by much contemporary scholarship and textbook writing.

This dilemma is already decades old. In her 1964 masterwork “Against Interpretation” (republished in Against Interpretation and Other Essays, New York: Delta, 1966), Susan Sontag argued for less “hermeneutics” and more “erotics” of art. Paint Made Flesh is case in point. Whereas the exhibition may not break new ground methodologically, it reminds us of the potent, inexhaustible pleasures of looking at art. If we do not always feel neurons firing, the alternatives—of having a work of art make the hair on the back of your neck stand up, of the sheer visual power of a single painting leading to euphoric mumbling, of remembering that paintings are as much about viscera as they are about intellect—are more than enough.

Though Paint Made Flesh does not answer all of the questions it presents, this is in part because we, collectively, may not be asking the right ones, or that we are still asking the same ones. This is the excitement and promise of such an exhibition—that there are more questions to answer, more questions to ask, and so much fertile territory left to navigate. Despite its faults, Paint Made Flesh should be mandatory viewing. Its searching example is one that should be widely emulated, and the extent to which it restores our faith in the power of the object cannot be underestimated, nor should it be ignored.

Adrian R. Duran

Assistant Professor, Art History, Memphis College of Art