- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Enthusiasts of early twentieth-century American art have long recognized George Bellows’s facility for powerful draftsmanship, yet his energetic, even boisterous, paintings and lithographs remain appreciably better known than his drawings. The artist made hundreds of original works on paper, largely black and white, now hidden in museums and private collections across the country. Their broad dispersal may account, in part, for the limited scholarly attention paid this fascinating aspect of the artist’s work. The exhibition The Powerful Hand of George Bellows: Drawings from the Boston Public Library begins to redress this lacuna by showcasing works from one of the key repositories of Bellows’s works on paper. Presented with a critical mass of thirty-two drawings, the viewer has the rare opportunity to revel in Bellows’s vigorous slashes of black, greasy crayon, and, on occasion, expressively precise pen and ink. Dense networks of animated lines suggest an impulsive conception, yet close observation reveals Bellows’s seemingly innate and purposeful placement of form and detail. Chronologically, the featured drawings cover the entire seventeen-year span of Bellows’s career. The earliest dates to 1907, just three years after Bellows (1882–1925) moved from his native Columbus, Ohio, to New York City in search of his artistic destiny. The exhibition concludes with drawings from the end of the artist’s tragically short life as he moved beyond his signature urban subjects to concentrate his graphic work on intimate portraits and commissioned illustrations.

Drawings were integral to Bellows’s creative being. During his lifetime, the artist featured them as finished works of art in high-profile exhibitions and discovered a market for them among major museums, including the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. Other slighter, drawings, often devoted simply to a single figure, functioned as preliminary sketches for lithographs and paintings. By far the largest audience for Bellows’s drawings was the one that saw his illustrations in popular periodicals. His career as an illustrator began with mild social commentary in the politically charged The Masses and evolved into a significant source of income. For magazines such as Good Housekeeping, Hearst’s International Magazine, The Century Magazine, and Collier’s, Bellows conjured up visualizations of now-forgotten popular fiction, such as H.G. Wells’s utopian Men Like Gods, and Irish author Donn Byrne’s romantic tale The Wind Bloweth. These monochromatic endeavors both satisfied Bellows’s fascination with the balance of light and dark, equally evident in his oil paintings, and met the technical demands of translating imagery into a mass-produced format.

Prominent banker Albert H. Wiggin donated a significant number of Bellows’s prints and drawings to the Boston Public Library between 1941 and 1951. Primarily a collector of Old Master and nineteenth-century prints and drawings, Wiggin gave the library an impression of each of Bellows’s editioned lithographs and a group of drawings selected on the basis of their relationship to the prints. Ten of these lithographs are also featured in the exhibition. Bellows’s widow, Emma, supplemented Wiggin’s gift by donating comparable drawings from her husband’s estate. Although Bellows died in 1925 at age forty-two from medical complications following a ruptured appendix, this significant acquisition indicates that he remained a much-lionized American artist, having achieved both critical acclaim and widespread fame while still in his twenties. His popular, appealing subjects centered on life in New York City, but also encompassed imagery drawn from his summer trips to New England and Woodstock, New York.

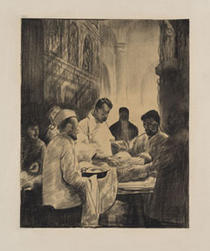

Bellows’s graphic work, in particular, reflects his keen visualization of human nature as he highlighted the physical and emotional idiosyncrasies of the people and scenes he observed in these diverse communities. The diminutive pen-and-ink sketch of Prayer Meeting (1913) indicates how intuitively he grasped his subjects’ essential expressive qualities. A modicum of descriptive line offers individualized characterizations of a small group of worshippers in a rural Maine church. This satirical drawing later because the inspiration for an illustration for The Masses and for a lithograph of the same title.

Arranged chronologically, the works in the exhibition provide not only evidence of Bellows’s command of the medium but a fascinating overview of his development as a draftsman. The artist’s initial graphic efforts included topical images made in tandem with Robert Henri and John Sloan, fellow admirers of Honoré Daumier, such as the evocative drawing Dogs Early Morning (1907), a quintessential “ash can” scene of a deserted street on the Lower East Side inhabited by mangy, stray dogs. Bellows tended to fill his early drawings with human figures in oppressive urban contexts, picking out descriptive detail in pen and ink and allowing the backgrounds to dissolve into a shadowy veil. By the early 1920s, Bellows relinquished caricature’s shorthand; congested scenes dotted with competing mannerisms give way to more serene and carefully modeled figures. He switches to a buttery soft, black crayon for his depictions of family and friends, eloquent expressions of intimate domesticity. Bellows never relinquished his passion for black-and-white drawings; they far surpass in number those rare works on paper Bellows tinged with color: his watercolors, colored crayon drawings, and pastels.

By their very nature, the unvarying smooth surface of the lithographs cannot convey the drawings’ vibrant immediacy. The juxtaposition of drawing and related print, however, vividly illuminates the artist’s conceptual and technical transfer of an image from one medium to another. In 1916, when Bellows somewhat daringly undertook lithography, a printmaking process not then in vogue, he based his prints on existing drawings such as Splinter Beach (1912) and Preliminaries (1916), both genre scenes of urban life. Businessmen’s Class (1913), intended for reproduction in The Masses, employs a wealth of detail to describe an exercise class at New York City’s YMCA where a motley group of men vainly attempt to emulate their instructor’s taut, imperious posture. In the transfer of drawing to print, well-defined forms and clear spatial relationships are sacrificed for visual unity as the lithographic process merged individual lines into evenly toned areas. Absent the briskness of the original strokes, the lithographs achieve their expression through theatrical contrasts of highlight and deep shadow.

On the visitors’ behalf, one wishes the distinction between lithograph and drawing had been explicated within the exhibition itself. The labels focus on crucial biographical information that places individual works in the context of Bellows’s life and, to a certain extent, within the broader narrative of the American realist tradition. Still to be explored by curators and conservators is the development of Bellows’s content, process, and materials considered within the full scope of his drawing production. (The detailed cataloguing of each object in the accompanying publication is a fine foundation for future study.) A close reading of Bellows’s drawing oeuvre as a whole, including his employment of photographs, the monoprint technique, and transfer lithography, as well as his penchant for recycling imagery, are sure to come. Such scrutiny would pose new questions of these works on paper, rightly presented in the exhibition as masterpieces of twentieth-century American drawing.

Jane Myers

Senior Curator, Prints and Drawings, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas