- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

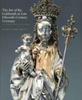

The Kimbell Museum’s Masterpiece Series introduces select works from the museum’s permanent collection to an audience both lay and specialist. As part of this series, Jeffrey Chipps Smith’s The Art of the Goldsmith in Late Fifteenth-Century Germany: The Kimbell Virgin and Her Bishop perfectly blends the often neglected art of careful connoisseurship with a wealth of visual and historical context. There is far more than one would suspect in the brief eighty-six-page text as Smith examines the silver-gilt Kimbell Virgin in exacting detail. He produces a rich visual analysis that explains technical production and describes the training and working methods of the Renaissance goldsmith. The historical, ritual, and religious background of the commission as well as the crucial and topical issue of provenance provide a variety of approaches to the study of the object.

Abundant illustrations allow the reader to participate fully in the process of looking, with incredible details that come close to satisfying those of us whose hands get a little itchy when exposed to really good sculpture. Photographs of the object reveal surfaces from both the outside and the hollow inside, and even, in a series of delicately eerie x-radiographs, expose the Kimbell Virgin’s original construction. In addition to examining the object at hand, Smith provides numerous period works for comparison, including wooden and metal sculpture, prints, and paintings both Northern and Italian.

In the first section of the book, Smith pores over details of the richly worked surface of this rare and well-preserved example of the goldsmith’s art. Wearing an intricate golden crown set with twelve semi-precious stones, the Kimbell Virgin holds the Christ child on her right arm and stands on a crescent moon. Made for Bishop Wilhelm von Reichenau of Eichstätt sometime around 1486, the silver-and-gilt statuette depicts the Virgin of the Apocalypse, a type taken from Revelations that became especially popular beginning in the late fifteenth century.

In addition to describing the technical aspects of silver parcel-gilding, Smith examines the fine details of chased and polished metal, noting both the virtuosic craftsmanship and the skillful handling of pose and facial features, the delicate gestures, curling hair, and the exuberant drapery-folds that are characteristic of German sculpture from this period. In both illustrations and words, the statue is carefully disassembled. The underside of the base reveals the date but no punchmark that would aid in finding the artist. The base is treated with Gothic ornament, scrolling grapevines that refer to the Eucharist, six musical angels, and six standing saints; and it likely housed a holy relic in its hollow compartment. Smith identifies the saints as important to the city of Eichstätt, the seat of the patron, Bishop Wilhelm. These, along with the date and Wilhelm’s coat of arms, correlate with the bishop’s patronage referenced in church records.

The second section begins by contextualizing the Virgin within broader Renaissance concerns. Strong connections link the art of the goldsmith with the art of the print engraver. Albrecht Dürer’s widely distributed woodcut series The Apocalypse, first published in 1498, fed a fascination with all things apocalyptic at the turn of the half-millennium. Israhel van Meckenem’s engravings of the Virgin of the Apocalypse, one from the 1490s and one from 1502, are just two examples of images that were readily available to a broad and receptive public. Changing devotional habits—an emphasis on a more private, personal type of devotion called the Modern Devotion—reinforced the demand for images that could be used for meditative purposes. Smith also looks to Italy for examples of art created for personal devotion rather than public ritual. Another Kimbell Museum piece, Andrea Mantegna’s devotional painting of the Virgin and Child (ca. 1485–88), makes a perfect companion to the Northern Madonna, and the text encourages museum visitors to seek out both for comparison.

In the third and fourth sections, Smith investigates the art of the goldsmith in general and the making of the Kimbell Virgin in particular. He explains the importance of collaboration between goldsmiths, sculptors in wood, painters, and designers, such as printmakers. Although no drawing or maquette exists for the Kimbell Virgin, Smith provides a compelling example of such collaboration by introducing a 1497 metalpoint drawing of St. Sebastian by Hans Holbein the Elder that is translated, almost stroke for stroke, into a silver-gilt version by another unknown Augsburg goldsmith. The question remains whether a luxury item like the Kimbell Virgin was the final product of a collaborative effort between a designer and the goldsmith. With no signature or stamp to help, the attribution to an unknown Augsburg goldsmith must rely on circumstantial evidence. Although the Kimbell Virgin remains anonymous, the sophistication and elegance of her execution leads to the hope that other works by this master, perhaps in the form of drawings, will surface in time.

Smith next places the statuette into the historical context of the patron and his Marian devotion. Bishop Wilhelm founded institutions, commissioned buildings, and helped establish several convents, as well as the University of Ingolstadt. He played a major role in the expansion of Eichstätt Cathedral and instituted a new Marian feast day in 1488. His devotion to Mary is evident in his many commissions in her honor, and is visually documented in a miniature illustration from the Pontifikale Gundekarianum. Marian piety began to rise in the Middle Ages and reached its apex by the late fifteenth century. Debates over Mary’s immaculate conception culminated in papal encouragement which, although not instituted as official Catholic doctrine until the nineteenth century, made images of Mary as the Queen of Heaven tremendously popular. Although there are scant examples of other such lavish sculptural representations, the Kimbell Virgin epitomizes a type of image that permeated European religious devotions, especially in countless printed and painted versions that met the needs of a wide segment of the population. As such, the bishop’s Virgin, although practically singular in terms of medium, stands as evidence of a powerful cult of the Virgin that touched all levels of society.

The final section traces ownership of the statuette by using early records and photographs from the nineteenth century. Smith recreates the set of circumstances that account for the Virgin’s whereabouts between the last mention of her in the fifteenth century and her appearance in the 1885 catalogue of Mayer Carl of Rothschild’s collections. In between these two dates lies considerable upheaval: first, the tremendous devastation brought about by the Thirty Years War in the seventeenth century; then occupation during the Napoleonic Wars, whose subsequent desecularization of church property rearranged the fabric of much European culture. But it is the Second World War, with the inherent dispossession of so many Jewish collections, that still causes repercussions in the art world today, making the issue of provenance more relevant than ever. For this reason the final chapter of the Kimbell Virgin is crucial not just from a historical point of view, but also as a public statement on behalf of the museum about how objects are passed from one owner to the next and how this particular work came to be so far from its original context. Public awareness of the ethical implications of art collecting and museum acquisition have been heightened in recent years due to looting in the current Iraq war. As Smith so ably demonstrates, the connection between regional unrest and issues of legal possession has a long history in all cultures.

Susan Maxwell

Assistant Professor, Department of Art, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh