- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

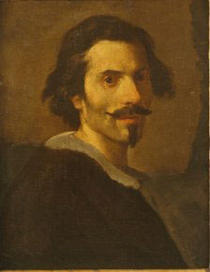

Bernini pittore, the title of the first exhibition devoted exclusively to Gianlorenzo Bernini’s painterly practice as well as of the accompanying catalogue, is a provocative reconstruction of this lesser-known aspect of the Baroque artist’s multidisciplinary career. Conceived and curated by Tomaso Montanari for the recently restored Palazzo Barberini in Rome, the comprehensive exhibit and catalogue offer a new monograph on Bernini’s painting under a purposely familiar title. Montanari’s version of “Bernini pittore” is preceded by two catalogue raissonnée of the same name: Luigi Grassi’s pioneering monograph, Bernini pittore (Rome: Danesi, 1945), and the recent book by Francesco Petrucci, Bernini pittore: dal disegno al “maraviglioso composto” (Rome: Ugo Bozzi, 2006). While Petrucci’s subtitle indicates a more expansive, multimedia development from Grassi’s fundamental work, Montanari’s repetitive tag strives for originary status. Indeed, like a palimpsest, the installation and catalogue seek to repaint the current image of Bernini as painter, applying atop the old a fresh portrait of the artist.

Attribution is the project of Bernini pittore. In this essential respect, Montanari’s endeavour necessarily differs little from those of his predecessors, all of whom have been forced to grapple with the almost complete absence of documentary evidence securing the authorship, let alone the dates, of so-called Bernini paintings. Since Antonio Muñoz (in a 1920 article), followed by Luigi Grassi and Valentino Martinelli (in a series of essays from the 1950s onward), assembled a disputed corpus of about fourteen autograph paintings, this group has been augmented by scholars, no doubt emboldened by the claims of Bernini’s biographers that there are between one hundred and fifty and two hundred paintings to be discovered. The progress of Bernini attributions seems to be aspiring to these numbers, with half the essays included in a recent book of new and reprinted essays (Bernini e la pittura, Rome: Gangemi, 2003) devoted to identifying works by Bernini’s hand. The zenith of this activity of making new attributions was reached by Petrucci, whose recent monograph identified over fifty autograph paintings from private and public collections. Against this quantitative and market-friendly trend, Montanari puts forward a seductive qualitative argument. In striking contrast to those of his predecessors, especially Petrucci, Montanari’s attributions are distinguished by radically cautious and judicious connoisseurship: only paintings of “superb” quality can be considered autograph. The result is a controversially small yield—sixteen in all—of canvases “securely” attributed to Bernini. My review will not address the specifics of agreement or disagreement with Montanari’s polemical attributions, but, rather, will focus on his exploration of the historical context for Bernini’s engagement with painting.

If attribution and the attendant issues of style and chronology provide the necessary bases upon which the study of Bernini’s activity as a painter must be established, Montanari’s interest in defining the function of Bernini’s painting breaks new ground. The issue of why and under what conditions Bernini painted was first addressed in Filippo Baldinucci’s 1681 biography of the artist wherein he claimed that Gianlorenzo painted for “mere pleasure” [mero divertimento]. Many scholars accepted Baldinucci’s claim without question. Grassi, for example, asserted that “the Bernini who wields brushes is nothing more than improviser, a dilettante” (18). In Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750 (London: Penguin Books, 1958), Rudolf Wittkower stated that “for Bernini painting was a sideline, an occupation . . . and to all appearances he treated the whole matter lightly” (112). If scholars have more recently demonstrated the seriousness with which Gianlorenzo undertook painting, they have not been able to offer a more nuanced portrait of the circumstances under which Bernini was motivated to paint. Montanari sheds new light on this issue by examining Bernini’s rapport with a novice and largely anonymous community of painters in Rome, his designs for large-scale public paintings, and his practice of giving gifts of paintings to intellectuals and noble patrons. Offering evidence for the function of the artist’s paintings that encompasses the private and the public realms, Montanari subtly sustains and challenges Baldinucci’s claim.

The impressive exhibition is comprised of twenty-five autograph works in different media (the sixteen autograph paintings, eight drawings, and one sculpture) and nine non-autograph works executed by Bernini’s students (seven paintings and two drawings). These are culled from various private and public collections in Europe, Britain, and North America. Even though Montanari’s basic aim is to establish and display in its entirety a new corpus of securely attributed works, the installation does not fixate on discriminating the work of the master from that of his followers. Rather the exhibition, mostly work in two genres—portraiture and historical (religious) painting—is subdivided thematically across six rooms: “Self-Portraits,” “Non-Autograph Self-Portraits” (portraits depicting Bernini, but painted by followers), “Portraits without Patrons,” “Portrait Drawings,” “Histories without Action,” and “Bernini as Inventor” (history paintings designed by Bernini and executed by others). In text panels the viewer reads Montanari’s arguments for Bernini’s style and how it is to be distinguished, particularly in the realm of portraiture, from the work of students and followers. But with only three disputed non-autograph portrait comparanda on view (displayed as a group in a separate section), Montanari’s installation offers less opportunity to assess his criteria than might have been desirable.

The exhibit is dominated by candid visages of unnamed subjects captured, seemingly unselfconscious, in mid-expression and painted with sketchy, vigorous brushstrokes. For the viewer familiar with Bernini’s astonishingly lifelike sculpted portraits commissioned by nobles, princes, and popes, these vivid portraits, mostly anonymous, offer an informal and rarely seen alternative to Bernini’s activity as a sculptor among the nobility. The intimate installation of the works in small groupings heightens the impression of the painter’s extraordinary familiarity with his subjects. And though Bernini pittore is chiefly a portraitist, the few extant history paintings on exhibit demonstrate that the artist’s facility for sensitive observation of the individual palpably transcends the boundaries of genre. The history paintings, executed on canvases only slightly larger than the portraits and hung in similarly small groupings that encourage close viewing, are experienced as intimate engagements with persons. Even when standing before Bernini’s stunning full-length figure of a sorrowing Christ, an altar-sized showstopper, the viewer encounters a disquietingly humanizing representation of a solitary, dejected Christ who leans, almost imperceptibly, toward the foreground of the canvas as though conscious of the spectator’s remarks.

The exhibition catalogue features Montanari’s monographic essay on Bernini as painter and four shorter essays on related art-theoretical, biographical, and multimedia issues by scholars who have previously published on aspects of Bernini’s multidisciplinary career. A descriptive inventory of disputed paintings is invaluable, providing a direct confrontation with the existing literature where Montanari justifies his numerous rejections of previous attributions. Also essential is the compilation of known sources and documents from 1624–1750 that mention Bernini’s paintings or his activities as a painter.

Montanari’s opens his five-part essay, “Storia di Bernini pittore,” by establishing new stylistic and chronological parameters for the study of Gianlorenzo’s painting. Montanari maintains the long-established notion that Bernini emulated contemporaries working in the neo-Venetian tradition. Yet in contrast to the prevailing view that Bernini’s stylistic development as a painter was discontinuous, non-sequential, and experimental, Montanari argues for five discrete phases of influence and evolution. Bernini’s stylistic progress begins with his approximation of the manners of Guercino, then Lanfranco, briefly Vouet, and, shortly thereafter, Velazquez, before arriving at a unique manner, heretofore unrecognized, around 1635. The specialist will note Andrea Sacchi’s conspicuous absence from this slightly uncanonical list. Montanari suggestively posits Lanfranco’s dramatic chiaroscuro and dynamic composition as an alternative. Perhaps more provocative is Montanari’s contribution to the frequently asked question of what, exactly, was the result of the presumed 1629 encounter between Velazquez and Bernini. Going beyond issues of style, Montanari posits that it was from the Spaniard that Bernini learned how to represent a sitter’s “psychological essence.” This claim will elicit scepticism, for while it is possible to recognize a heightened interest in the representation of interiority in Bernini’s paintings around 1630, one cannot ignore the psychological expression he managed to capture in his earlier canvases. Ultimately, in locating a strand of influence outside Italian tradition, Montanari seeks to show that Bernini had a wholly singular style. For Montanari, this is evident in what he sees as Bernini’s last phase, a unique synthesis of the aforementioned masters, which Montanari calls “emotive illusionism.” In the end, Montanari’s narrative of evolution offers a neat sequence of progress, ambitious given the small size of the corpus he has defined. In spite of the problem endemic to the subject of style, Montanari’s claims succeed in viewing Bernini with a fresh eye, raising unexpected questions and undoubtedly stimulating fruitful debate.

In the second section of the essay, “L’accademia di pittura,” Montanari provides new documentary evidence to substantiate an argument made in one of his previous essays (“Bernini e Rembrandt, il teatro e la pittura. Per una rilettura degli autoritratti berniniani,” in Bernini e la pittura, Rome: Gangemi, 2003, 187–201) that between 1632 and 1642 Bernini oversaw an academy of painting. Montanari deduces from this that the existence of numerous lesser-quality portraits of Bernini, considered by many scholars to be autograph self-portraits, must be student works. He suggests that copying and adapting self-portraits by the master was an essential part of artistic training, thus positing a didactic function for Bernini’s painting. Montanari further argues that acting was also fundamental to artistic training at Bernini’s academy. In a perceptive reconstruction indebted to Svetlana Alpers’s theatrical portrait of Rembrandt’s studio (Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), Montanari presents evidence that Bernini’s students designed and performed in yearly stage productions organized by the master so they might acquire tools of persuasion that could be translated into paint.

In “Storie senza azione,” part three of the extended essay, Montanari argues that Bernini painted biblical narratives with the sensitivity of a portraitist—that is, Gianlorenzo was more concerned with representing the psychology of the individual(s) than the story itself. He thus interprets Bernini’s David (ca. 1623), his Sts. Andrew and Thomas (1626–27), and his Head of an Apostle (ca. 1627–30) as character portraits, not narratives. Montanari suggests, however, that even though Bernini preferred representing psychological states to painting histories, he did not completely eschew narrative strategies. His argument is based on a novel iconographical reading of Bernini’s unusual representation of a full-length, seated Christ. Petrucci, who first published the painting in 2001, identified the work as an allegory of the Passion, a Christ patiens, and an explicitly non-scriptural scene. Montanari, by contrast, argues that the painting is an innovative representation of Christ Mocked (ca. 1635) as recounted in Matthew’s gospel. Bringing Bernini’s painting in line with a Counter-Reformatory drive to move the spectator, he suggests that the viewer “emotionally” completes the narrative by assuming the role of the mocking crowd. Montanari proposes, very suggestively, that Bernini eschewed traditional iconic or narrative formats (not only here, but routinely in his history painting) and engaged less in a narrative genre than in a representational modality—transitivity. Montanari’s correlation of Bernini’s transitive history paintings with Bellori’s enigmatic claim that Caravaggio painted “histories without action” also opens a new avenue of investigation that moves beyond musings on the formal influence of Caravaggio upon Bernini toward unexpected representational affinities.

The fourth section, “Bernini inventore,” explores the artist’s public role from 1630 to 1640 as a designer of paintings executed by other artists. Here, too, Montanari seeks to prove that Bernini’s strength is not in conceiving multi-figure history paintings, a genre in which he lacks invention compared to his single-figure narratives. Taking as his point of departure the Martyrdom of St. Maurice (1635–40), an altarpiece conceived by Bernini and painted by Carlo Pellegrini, Montanari notes that the composition is a “clumsy paraphrase of Poussin’s Martyrdom of Erasmus (1628–29)” (66). Montanari’s disparaging assessment is not unique. And like countless scholars before him, Montanari judges Pellegrini’s Conversion of Paul (1635) to be an even poorer composition, an “ugly” copy of a painting by Lodovico Carracci. In view of Bernini’s professed admiration for Poussin’s art, particularly the Erasmus altarpiece, it might be useful to reconsider Pellegrini’s altarpieces in less pejorative terms. Given the value of imitation in the early modern period as a strategy of artistic formation, of competition, and even originality, and considering Bernini’s own competitive imitation with Michelangelo, it is possible to imagine that he encouraged Pellegrini to engage in an overt paragone, however unsuccessful, with the French and Bolognese masters.

Montanari devotes the final portion of his essay, “Per un’interpretazione di Bernini pittore,” to the consideration of Bernini’s paintings as autonomous works. He convincingly argues that since Bernini did not paint upon commission the artist was free to design and execute his canvases under conditions of total creative freedom. Montanari further suggests that Bernini exercised a kind of market autonomy by offering his portraits of anonymous individuals as well as his pre-painted religious works to popes, nobles, and intellectuals as “diplomatic” gifts. Montanari is not suggesting that Bernini is here engaged in official diplomatic duty; rather, he envisions Bernini enacting a very personal (and shrewd) promotion of his talent as a painter. Montanari ultimately conjectures that Bernini and the recipients of his paintings valued the works first and foremost for their artistic merit.

In “I disegni di ritratto di Gian Lorenzo Bernini,” Ann Sutherland Harris convincingly argues that Ottavio Leoni’s animated drawings of noble Roman society, hitherto overlooked in discussions of Gianlorenzo’s graphic influences (which typically privilege the formal impact of Annibale and Agostino Carracci’s portrait studies), are fundamental to understanding Bernini’s formal conception of portraiture. This thoughtful study of the style and function of Bernini’s numerous and beautiful portrait drawings also suggests a means of dating Bernini’s graphic portraits according to the changing fashion for men’s shirt collars. Most perceptive is her deft analysis of Bernini’s technical skill, particularly the sophisticated manipulation of his limited materials of black, white, and red chalk, along with the very grain of the paper upon which he drew, to create the illusion of luminosity, texture, and flesh that rivals his illusionistic portrait busts. Indeed, it is through this lens that we might even see Bernini’s late self-portrait—created, uncharacteristically, using only carbon and white chalk—as a paragone with the monochromy of sculpture.

In “Bernini, la pittura e i pittori,” Alessandro Angelini explores Bernini’s assimilation of neo-Venetian painting in his sculpture, canvases, and design of illusionistic paintings for multimedia chapels executed by painters under his direction. Angelini offers a useful contextualization of Bernini’s neo-Venetianism within the circle of contemporaries, and he is most perceptive in the discussion of Bernini’s chapel decoration. Seconding Montanri’s argument for Lanfranco’s influence, Angelini suggests further that Bernini’s study of Lanfranco contributed greatly to the extraordinary illusionism of the composti. Indeed, Angelini argues that Bernini’s interest in contemporary advancements in illusionism is fully realized, even surpassed, by the painters that adopted Gianlorenzo’s visual language—Abbatini, Romanelli, Cortese, and Bacciccio—and whom he trusted to execute his pictorial decoration that traversed the limits of painting and sculpture.

Tod Marder’s essay, “Bernini, fanciullo prodigio della ritrattistica,” explores the biographical representation of Bernini’s prodigious talent as a portraitist. He focuses on the story of Gianlorenzo’s youthful encounter with Paul V, variously told by Paul Fréart de Chantelou in his diary of Bernini’s French sojourn (1665) and by the artist’s biographers, Filippo Baldinucci (1681) and Domenico Bernini (1713). His approach to the anecdotes as literary constructions, shaped by the diverse goals and themes of the authors, echoes the methodological aims recently set out in a provocative book of essays devoted to reading Bernini’s vitae as texts rather than documents (Bernini’s Biographies: Critical Essays, edited by Maarten Delbeke, Evonne Levy, and Steven F. Ostrow, University Park: Penn State University Press, 2007). Marder’s analysis of the biographies thoughtfully develops themes introduced in this collection, and he makes a particularly insightful reading of the parallel developed in Chantelou’s diary between Bernini’s famed precociousness and the promise shown by his son and sculptor, Paolo, at the French court. Among Marder’s many thoughts on Bernini’s early work, his formal analysis of the frame for the Santoni bust in Sta. Prassede not only offers a novel approach to vexed issues of attribution, but also intimates a rather precocious date for Bernini’s study of architectural ornament.

In the final essay, “Bernini e il paragone,” Steven Ostrow offers a nuanced investigation of the artist’s theoretical and practical engagement with the paragone debate. Moving between text and art, Ostrow mines Chantelou’s diary and the biographies for Bernini’s musings on various aspects of the relative merits of sculpture versus painting—difficoltà, universality, relief, color, truth—and then shows how these ideas were either realized or contradicted in Bernini’s sculptural practice. Beyond forcefully demonstrating that Bernini offered original contributions to what had become a rather repetitive, conventional comparison between the two arts, Ostrow lays a much-needed theoretical foundation for any discussion of the formal and illusionistic affinities customarily drawn between Bernini’s painting and his sculpture.

If the sotto voce grumblings of sceptics at the Bernini pittore exhibition are an early indication, Montanari’s polemical corpus of autograph works will stimulate heated debate. Indeed, attribution is sure to continue to be a disputed focal point of the scholarship on Bernini as painter. Nonetheless, Montanari’s textual iteration of Bernini pittore, including the accompanying essays, ultimately provides a more complex and dynamic picture than previously understood of the artist’s activity as a painter, of the function(s) of his paintings, and of the integral role painting played in Bernini’s multimedia imagination. Most significantly, Bernini pittore offers broader implications for the perception of Bernini as an artist in general by adding fuel to recent studies challenging long-held assumptions that Bernini enjoyed artistic autonomy in every realm. In particular, Montanari’s reading of Bernini’s autonomy as a painter of small, uncommissioned works presents a striking alternative to the artist’s sculptural and architectural projects, which are deeply embedded in court (largely papal) patronage. By defining this one medium as Bernini’s outlet for creative freedom, Montanari’s portrait of Bernini pittore offers a striking image of how precious and rare independence from patronal realities actually was, even for the most esteemed artists.

Carolina Mangone

PhD candidate, Department of Art, University of Toronto