- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Compared to his contemporaries such as Nicolas Poussin and Georges de la Tour, Philippe de Champaigne remains the one great painter of seventeenth-century France who has attracted little scholarly attention. Most scholarship reduces Champaigne’s artistic production to his portraits of Cardinal Richelieu and to his involvement with the Benedictine Convent of Port-Royal, seen as the stronghold of Jansenism in France and to which he gave his famous Ex-Voto (1662, cat. 57).

Champaigne dominated both religious painting and portraiture in Paris from his arrival in the capital from his native Brussels in 1621 until his death in 1674. The scope of his career is singular. No other painter in Paris worked through all the governments spanning from Maria de’ Medici to Louis XIV. Furthermore, Champaigne rarely painted mythological and allegorical pictures; his few landscapes are always religious in nature; the evolution of his style is difficult to trace; and little is known about the activities of his studio.

Curated by Alain Tapié and Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot, Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674): Entre politique et dévotion is the first retrospective devoted to the painter since the 1952 show at the Orangerie des Tuileries in Paris. This exhibition, currently on view in Lille, will travel to Geneva in a slightly different form. In Lille, the show presents about seventy of Champaigne’s paintings, two tapestries executed after his designs (ca. 1660, cat. 87; ca. 1662, cat. 88), and two pictures—Mater Dolorosa (after 1669, cat. 52) and Good Shepherd (after 1652, cat. 56)—attributed to his nephew and assistant, Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne.

The curators successfully present a comprehensive overview of Champaigne’s painted corpus. The upper gallery of the Palais de Beaux-Arts takes the visitor for a mostly chronological journey through Champaigne’s long and productive career, which the curators divide into five sections. The presentation of the paintings is sensible and traditional. The walls, consistently painted in a light beige color with a touch of grey, do not compete with Champaigne’s palette. Seeing the Ex-Voto at eye level was an extraordinary treat as it hangs too high in the Musée du Louvre. Only in Lille can the visitor inspect the painting closely, read the inscription, and see such minute details as the beads of the reliquary on Sister Catherine de Sainte-Suzanne’s lap. With skylights above the galleries, the lighting is fair on a grey day but remarkable when the sun appears in the usually overcast Lillois sky.

The inclusion of two of Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne’s paintings hanging next to their models by his uncle proved revealing. Jean-Baptiste’s Mater Dolorosa—a reduced version of Philippe’s (ca. 1669, cat. 51; the medium is oil on canvas rather than oil on wood as noted in the catalogue entry)—lacks the power of his uncle’s picture. The treatment of the folds of the drapery is flatter and its deep blue color less intense. The second pairing puts Jean-Baptiste’s artistic skills in a much better light. His Good Shepherd is not a slavish copy of Philippe’s (ca. 1652, cat. 55) but rather an intelligent and individual interpretation of the same composition.

Of the four portraits of Cardinal Richelieu exhibited (ca. 1635, cat. 13; ca. 1640, cat. 14; ca. 1642, cat. 22; after 1651, cat. 24), two are well known (14 & 22). The Chaalis Portrait of Richelieu (cat. 13) depicts the cardinal’s facial features more realistically than in the better-known version at the National Gallery of Art in London (not in the show). Hence, the Chaalis picture likely predates the more propagandistic and idealizing images in which Champaigne showed Richelieu as all-mighty Minister of France. The strange perspective, as noted in the catalogue entry, suggests that this portrait was the one painted to hang above the chimney of Richelieu’s bedroom in his Château de Richelieu. Cardinal Richelieu in his Library (cat. 24), here given to Champaigne, is probably a studio work, as first noted by Dorival (1992, cat. 88 [a list of citations appears at the end of this review]). One of the books on the shelf, Richelieu’s Traité [. . .] pour convertir ceux qui se sont séparez de l’Église, was published in 1651, nine years after his death. The heavy pentimenti on the right hand and the fact that the treatment of the drapery is virtually identical to that in the Sorbonne portrait (cat. 14) suggest a studio production. Another work that should be given to Champaigne’s studio is the Avignon Crucifixion (after 1655, cat. 73), which appears weak in terms of the handling of the paint when compared to his spectacular Grenoble version (1655, cat. 72).

The show opens with the Barnard Castle Portrait of Charlotte Duchesne (cat. 1; the oil painting is on panel rather than on canvas as listed in the catalogue entry), whom Champaigne married in November 1628. Sainte Fare Garnot proposes the date of circa 1628 for this portrait and does not address Lorenzo Pericolo’s convincing argument for a later date, closer to her premature death in 1638, based on her lace collar fashionable in the mid 1630s (Pericolo, 2002, 80). Moreover, while we do not have Charlotte’s birth date, Dorival associated her with the Duchesne child baptized on December 1, 1613 (1976, vol. I, 34). In the painting, her facial features are more representative of a woman in her early twenties than in her mid-teens.

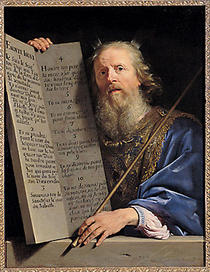

The Cincinnati St. Jerome (cat. 29), a recent and undisputed addition to Champaigne’s corpus, is a beautifully painted picture in perfect condition. Like several of Champaigne’s most spectacular portrait-like representations of saints—such as the Rennes Mary Magdalen (1657, cat. 50), the Milwaukee Moses (1648, cat. 32; only shown in Geneva), the Grenoble St. John the Baptist (1657, cat. 49), and the Stockholm St. Bruno (ca. 1655, cat. 74)—the St. Jerome, because of its remarkable composition and use of color, should be dated in the late 1640s/early 1650s rather than circa 1630–35 as proposed in the catalogue. This becomes apparent when compared, for instance, with the Houston St. Arsène (cat. 11), a signed and dated picture of 1635, which lacks the immediacy and compositional clarity of the later paintings.

Belonging to the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, the Vision of Sainte Julienne de Cornillon (ca. 1647, cat. 42; 47×38 cm; the dimensions in the catalogue entry are slightly off) is a tiny gem of painterly technique and iconographical refinement. The execution of the tear on her left cheek is only matched by the details of the pinkish red canopy fringes surrounding the altar in front of which she kneels. The story of the Cistercian Julienne (1192–1258) involves the cult of the Corpus Christi, so important for Port-Royal that in 1647 the nuns dedicated their convent to the Order of the Holy Sacrament and established the perpetual adoration of the Eucharist; they also symbolically exchanged their black scapular (seen here) for a blood-red one (seen in the Ex-Voto). Julienne had a recurring vision of a partly obscured moon, in Champaigne’s painting framed dramatically by an open window pane. During her prayers in front of the Holy Sacrament hanging above the altar, the mystery of the vision was revealed: the moon, in its bright splendor, symbolizes the Church, while the shadow represents the neglect of the celebration of the Corpus Christi during her lifetime (for a full discussion of the iconography, see Pericolo, 2002, 175–179). Sainte Fare Garnot proposes that this picture is a “bozzetto” for Jean Morin’s print (fig. 42; 178), while previous authors have suggested that this highly finished picture was created for private monastic devotion, a much more likely hypothesis (Dorival, 1976, vol. II, cat. 128; Le Dieu caché, 2000, cat. 63; Pericolo, 2002, 175–179).

The penultimate room of the exhibition focuses on Champaigne’s late work, rarely addressed in the scholarship because his stylistic evolution is a thorny topic. Noteworthy are the Toulouse Descent into Limbo, circa 1655 (cat. 90); the Angers Christ among the Doctors, signed and dated 1663 (cat. 92); and the Soissons Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter, circa 1664 (cat. 89), which needs minor cleaning (the upper right side of the painting has bits of what looks like either tiny mice or bird droppings). The Descent into Limbo is a remarkably original painting in terms of iconography and surely Champaigne’s most crowded picture. Ingenious vistas contribute to the grandeur of the Angers and Soissons paintings, something less present in Champaigne’s early works. By presenting about seventy of Champaigne’s pictures in a mostly chronological manner, the show raises fascinating questions about his stylistic evolution.

The catalogue contains six essays, entries on each painting, a bibliography, and a useful index. The illustrations are of good quality; when two versions of the same work exist, they appear next to each other on a double page, which greatly facilitates comparisons. The ninety-four catalogue entries are split between thirteen authors; Sainte Fare Garnot, Tapié, and Philippe Luez wrote over half of them. The catalogue entries are uneven in their depth and at times inconsistent in their format. For example, inscriptions and dates on paintings are not systematically cited (see for instance cat. 92), and some authors list related prints while others do not.

The first essay, Sainte Fare Garnot’s “Pour une biographie critique du peintre,” is a useful summary of the scholarship on Champaigne from Félibien’s notice to Dorival’s monograph (1976), though it does not include the most recent book on Champaigne (Pericolo, 2002). In “L’art de l’âme,” Tapié attempts the difficult task of reconstructing the sources of Champaigne’s spiritual development and its effect on his paintings. Some of his ideas, such as the influence of Saint-Cyran’s thoughts on Champaigne, are right on the mark. However, we cannot link Champaigne’s reading of St. Teresa of Avila’s writings to his work at the Carmelite Convent of the Faubourg Saint-Jacques around 1628–29, as the copy of her book listed in the Champaigne inventory was only published in 1670 (Dorival, 1971, 26).

In “Le contexte artistique bruxellois pendant la jeunesse de Philippe de Champaigne,” Sabine van Sprang summarizes the artistic milieu of Brussels in which Champaigne spent his formative years. Her most original contribution is her discussion of the possible influence of Wenceslas Cobergher (1557/61–1634), a student of Marten de Vos who, after having spent some twenty years in Italy, was called back to Brussels by the archduke around 1605–6. Unfortunately, only one painting securely dated after 1606, the Entombment (fig. 4; 52), seems to have survived, limiting further comparisons with Champaigne’s work.

Vincent Carraud’s “Admirer l’original: la Cène de Port-Royal de Paris” and Sainte Fare Garnot’s entries on the same paintings (cat. nos. 43 & 45)—Champaigne’s three versions of the Last Supper—contradict each other. It seems the authors only realized this when reading the proofs of the catalogue (see n. 18; 65).

Champaigne’s three versions of the Last Supper share the same overall composition, but differ in size; they also share similar colors for drapery, poses, and gestures, as well as the presence or absence of three objects (a pitcher in the foreground, a basin with a towel on the right, and a vase behind the basin). Two are in the Louvre, the so-called Small Last Supper (cat. 43) and Large Last Supper (fig. 3; 63), while the third painting, also called the Large Last Supper, is in Lyon (cat. 45). The great questions have always been which one of the three did Champaigne paint first for the altar of the church of the convent of Port-Royal in Paris (ca. 1648), which one did he paint a few years later for the convent of Port-Royal des Champs (ca. 1652), and how does the third version, seized in Paris during the Revolution, fit into all of this?

Using a preparatory drawing in the Louvre (fig. 43; 180), Sainte Fare Garnot proposes that the Louvre Small Last Supper is a modello for the large Louvre picture, itself painted for the Port-Royal de Paris. The undated Louvre drawing, which Le Leyzour and Lesné did not accept as autograph, does not buttress the writer’s argument (Philippe de Champaigne et Port-Royal, 1995, cat. 28). For Sainte Fare Garnot, the Lyon picture was done for Port-Royal des Champs because its brighter light and golden hues were more adapted to that church (now destroyed), which he asserts was a darker space than that of Port-Royal de Paris (although without mentioning his sources). According to Carraud, Champaigne painted the Lyon picture for the Parisian convent and the Louvre Large Last Supper later for Port-Royal des Champs; his reasoning is that the latter is a more classical and restrained picture, with fewer objects and gestures to distract. He does not address the destiny of the third painting, the Small Last Supper in the Louvre. Carraud’s conclusions are similar to those of Le Leyzour and Lesné, still the best and most convincing discussion on the subject (Philippe de Champaigne et Port-Royal, 1995, 119–133). Carraud’s essay is an important contribution to the iconographical interpretation and meaning of Champaigne’s Lyon Last Supper, which can also be applied to the other two versions. Carraud explains that Champaigne’s picture must be interpreted within Port-Royal’s attachment to and devotion of the Holy Sacrament.

Karim Haouadeg’s “Philippe de Champaigne et l’Académie” is a short essay divided into three parts. The first summarizes the pedagogical functions of the conferences within the Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Champaigne was one of the Academy’s founding members in 1648, and his reception piece, St. Philip (1648, cat. 77), is in the show. The second part finds a common thread among Champaigne’s eight conferences, namely his sense of responsibility as a teacher who provided more practical and technical advice than other professors at the academy. The third takes on Champaigne’s famous conference on Poussin’s Rebecca at the Well in the Louvre, which, according to the author, can be properly understood only when one becomes aware of the distinction Champaigne made between “the order of nature” and the “order of grace.” Unfortunately, he does not adequately explain the distinction.

In the last essay, Pierre-Antoine Fabre pays homage to the late French philosopher Louis Marin and his posthumous semiological study of Champaigne (1995). In his book, Marin used the case of Champaigne and his involvement with Port-Royal not only to explore the functions of images and of written words in painting but also to understand the relationship between religious images and spiritual representations.

The visitor to the exhibition will come away impressed with the beauty and intelligence of Champaigne’s art. His undeniably brilliant sense of color, perfectly thought-out compositions, and subtle iconographical refinement will encourage new scholarly interest in this master. While slightly smaller, the exhibition in Geneva will prove important, especially in bringing together Champaigne’s two versions of Moses (Milwaukee; and 1663, cat. 31, Amiens) as well as two of his Crucifixions (Grenoble; and before 1655, cat. 71, Trafalgar Galleries, London).

Cited books and articles:

Dorival, Bernard. “La bibliothèque de Philippe et de Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne,” Chroniques de Port-Royal 19 (1971): 20–36.

Dorival, Bernard. Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674). La vie, l’oeuvre et le catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre. 2 volumes. Paris: Laget, 1976.

Dorival, Bernard. Supplément au catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre de Philippe de Champaigne. Paris: Laget, 1992.

Marin, Louis. Philippe de Champaigne ou la présence cachée. Paris: Hazan, 1995.

Pericolo, Lorenzo. Philippe de Champaigne: “Philippe, homme sage et vertueux,” Essai sur l’art et l’oeuvre de Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674). Tournai: La Renaissance du livre, 2002.

Cited exhibition catalogues:

Philippe de Champaigne. Exposition en l’honneur du trois cent cinquantième anniversaire de sa naissance. Paris: Orangerie des Tuileries, 1952 [curated by Bernard Dorival].

Philippe de Champaigne et Port-Royal. Magny-les-Hameaux: Musée national des Granges de Port-Royal, 1995 [curated by Claude Lesné and Philippe Le Leyzour].

Le Dieu caché: les peintres du Grand Siècle et la vision de Dieu. Rome: Académie de France à Rome, 2000 [curated by Olivier Bonfait and Neil MacGregor].

Anne Bertrand-Dewsnap

Teaching Associate for Core Art History, Department of Art and Art History, Marist College